|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, all set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-FOUR:

On 19th August 1967, 26-year-old Australian-citizen Edward Wahlstrom-Lewis paid a visit to the Rupert Court Club at 8 Rupert Court in London's Chinatown. Entering the club, Edward was given two options; spend £4 to sit and chat to a pretty hostess for a bit, or spend £8 for the whole night. He assumed he was going to spend the night with the lady and (in return) get some sexy time. But when he realised all he was going get was some idle chit-chat, and no nookie, Edward lost his rag and put three men in hospital. This is a truly bizarre story about a man who wanted some kiss kiss, what he delivered was bang bang.

CLICK HERE to download the Murder Mile podcast via iTunes and to receive the latest episodes, click "subscribe". You can listen to it by clicking PLAY on the embedded media player below.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of 8 Rupert Court where Ted Wahlsdtrom-Lewis shot Roy Martinson is marked with a bright green coloured raindrop near the words Leicester Square. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

SOURCES: As this case was researched using some of the sources below. Archive File - https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/record?catid=6276725&catln=6 MUSIC:

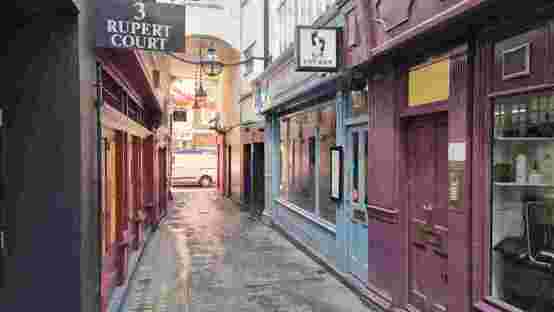

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: Welcome to Murder Mile. Today I’m standing in Rupert Court, W1; one street north of the death of Ken Snakehips Johnson, one street north-east of the club where the First Date Killer met his date, and just a few feet from the wannabe gangsters who acted like bell-ends - coming soon to Murder Mile, the YouTube channel. Nestled beside the ornate gates to Chinatown, Rupert Court is a narrow alley connecting Rupert Street and Wardour Street. At roughly six feet wide, one hundred feet long and three storeys high, every inch of space has a shop squeezed in; whether a Malaysian café, a Thai restaurant, a decent pub, a branded pizzeria and at 8 Rupert Court is Step-In - a one-stop shop for your relaxation and wellbeing needs. Of course, being a respectable establishment providing massage in this area, you half-expect to see a pasty wheezing pervert with a shuffling fist, hairy palms and bulging pants being politely ejected with a firm boot, as the only ‘happy finish’ he’ll receive here is in his soul. But that mistake is easy to make. Back in the sixties, Rupert Court was full of mucky book shops and sleezy porn palaces. At number 8 stood the (imaginatively titled) Rupert Court Club; a cheesy clip joint where gaggles of drunk and horny men – desperate to see a bit of boob - paid over the odds to be fooled by the oldest trick in the book. One such man was Edward Wahlstrom-Lewis, an Australian on a night out with his pals. Expecting nookie but receiving nowt - whereas most men would pay-up and walk-out rather than suffer the shame of calling the cops – having been denied a little ‘kiss kiss’, he would deliver some ‘bang bang’. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide, and this is Murder Mile. Episode 164: Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang. The fascinating thing about murder is the tipping point. Everybody has a tipping point, that moment in life when a perfectly rational person is pushed beyond the limits of what they deem acceptable. For some, it can be the preservation of life, but for others… it can be something as simple as pride. Edward Robert Wahlstrom-Lewis, known as Ted was born on the 5th October 1941 in Shanghai, China. Raised two years into the Second World War and a full four years into the conflict between China and Japan – although Ted was still only a baby, his earliest memories were of a life behind prison bars. In 1943, with Shanghai occupied by Japanese forces, any Western citizen living on occupied land was interred in a concentration camp. Being Australian, the Wahlstrom-Lewis family were rounded-up with nothing but the clothes on their backs and separated, so his mother had to care for her son, alone. From the age of two, Ted spentthree years half-starved and ragged, as a prisoner-of-war in a cramped camp riddled with disease, filth and squalor, never knowing when the nightmare would end. It was no life for a child, and yet incarceration would become a familiar presence over his next three decades. In 1946, with the war finally over, the family were reunited and they returned to the safety of their home in Sydney, Australia. Being free, life should have got better. But for Ted, it would only get worse. In 1949, his father died of a heart-attack, leaving Ted and his three younger sisters without a dad. To try to regain a sense of stability for the family, his mother remarried. But when she fell ill, aged 8, Ted was put in a children’s home for 18 months - a second prison sentence for something he hadn’t done. With an erratic education, he attended several schools in Sydney and Wollongong, where he was described as an average student, who had issues with authority figures and often played truant. Aged 15, with his mother moving to the country, he stayed in the city and had little contact with her since. Ted would state that he had a good childhood, but with so much turmoil and upset, although everyone agreed he was a good bloke – because his first memories were of poverty - he was blessed with a strong sense of pride but cursed with a short fuse. So, whenever he felt cheated, he was easily stung. As a young lad, living alone, he tried his best to lead a good life. In 1955, he worked as an attendant at Underra Service Station. In 1956, he spent a year as a sales assistant at Mick Simmons Sports Shop. In 1957, he joined the Merchant Navy but never left port. And in 1958 he became a farm labourer in Wollongong. But frequently being in-and-out of work, by his late teens, he had turned to petty crime. Between March and June 1961, he was charged four times for twenty cases of theft, mostly for stealing cars but also an outboard motor. He was sentenced to 2 ½ years hard labour at Parramatta Prison, plus ten months for each charge which he served concurrently. In July 1963, having been released on bail, he fled to Melbourne and (in his own words) “lived of the proceeds of crime”. That same month, he was arrested and charged with five counts of shop-breaking, stealing and sentenced to five years. While held at McLeod Prison on French Island, he was further convicted of absconding legal custody and wilful damage, having attempted a prison break and was given a further nine months inside. Interestingly, he had no convictions for drunkenness, firearms or assault. In fact, the only unusual blip in his criminal record which hints at the crime which was to come was his first offence. As in May 1960, he was sentenced to six days hard labour for the unusually vague crime of ‘indecent behaviour’. On the 12th August 1966, Ted was paroled. Seeking a fresh start – not just from a life of crime, but also from his country – he cleaned-up his act, moved in with his grandmother, got a job as a fisherman, and - through honest toil and sweat - he saved-up his money so he could start a new life in England. On 26th July 1967, Ted arrived in London. In the interim, he stayed at a friend’s flat at 87 Ridgemount Gardens in Bloomsbury, he started working as a van-driver for a company called Instant Van earning a regular £14-a-week, and as a 26-year-old singleton, he was hoping to find himself a nice lady. Being a big drinker, it wasn’t uncommon for him to sink 15 bottles of beers a night, but he wasn’t a drunk. Three weeks in, Ted was still finding his feet, but so far, his new life was going well… By all accounts, Saturday 19th August 1967 was just an ordinary day. At 5pm, having finished his shift, Ted parked up the white Ford Transit in the garage at 9 Bristol Mews, just north of Paddington Station. Having been paid, he had already started saving to rent his own place as he didn’t want to keep kipping in his mate’s spare bed forever. But as this was Saturday night, he felt he deserved a little blow-out. At 6pm, Ted, Ken Smith (who was an old pal) and Martin Penny (who owned the flat) headed out for a night on the tiles in Martin’s black Armstrong Sidley. With no drink drive limit, Martin could happily sink a few suds and drive with impunity, as long as he didn’t hurt anyone. But he didn’t. Being sensible, he had a few but not too many, and although the two Aussies liked boozing, they weren’t dickheads, At 6pm, they headed to a pub in Bethnal Green and stayed for roughly 30 minutes. They had fun, the mood was good, and they all got on well. There were no issues, arguments or moments of conflict. If anything, they could have stayed there all night. But they didn’t. At 9pm, they arrived at a pub called the Cockney Pride, just off Piccadilly Circus. As before, they had a few beers, a few laughs and there was nothing to suggest that this night was about to turn sour. At 10pm, Ted said he “wanted a dance”, the other lads liked the idea, so they left and headed to Soho. It made sense, as this was an area synonymous with fun. Whatever floated your boat, Soho had a club to assuage the most specific of tastes; whether live music for the groovers, casinos for the cash flashers and something decidedly seedy for those whose idea of fun was bouncy boobs and bobbling butts. Like any city, it had its dangers, but taking that risk was part of the deal. Even a nice night out might end up with someone being fleeced, slapped or stabbed. But as these lads weren’t looking for trouble, just fun, even though Ted had a quick-temper, both Ken & Martin knew what to do if he lost his rag. At 11pm, they walked up the south-side of Wardour Street into what was yet to become Chinatown. Passing the dark-lit sleaze and flashing neon signs of a nearby alley, at 33 Wardour Street, they tried to get into the Whiskey-a-Go-Go – an infamous music venue which that year alone had hosted such greats as The Drifters, Ben E king and Stevie Wonder – but being full, they had to look elsewhere. The streets were busy, if a little aggressive, as the hot night made the drunks jittery. Beside the arched entrance to Rupert Court, Ted saw a Chinese guy agitatedly barking in broken English to two bobbies about how he’d been robbed by a woman. The lads tittered as they secured their wallets, knowing he probably wasn’t the first man she had fleeced and he wouldn’t be the last. Welcome to Soho. For about 15 minutes, the lads tried a few other venues, but got no joy. It was then that Ted changed his mind. He still wanted to dance, but a different kind of dance. Being single and (if he was honest) a little lonely as a stranger in a new country, he couldn’t be arsed with the hassle of chatting up a girl and buying her a drink, in the remote hope of getting a quick kiss and a little fondle - if he was lucky. What he needed was a place where some sexy-time with a pretty lady was a dead cert, as feeling a little bit horny, he had a solid gold boner in his pocket which he didn’t want to waste on a wank. At 11:30pm, beside the Whiskey-a-Go-Go, as his pals waited outside, Ted entered Rupert Court. This thin dark alley - four times taller than it was wide – was bathed in a sickly neon glow which pulsed like hot blood into a throbbing cock, as the sinister shadows foretold of both terror and thrills within. With signs flickering in single syllable words like ‘girls and ‘nude’ - as clearly long words are impossible to read when you’ve got a hard-on - in this seedy alley there was no denying what was for sale – sex. Along both sides were several ‘hostess’ clubs; including the Two Decks, the Casino and the Alphabet, many of which offered a lap-dance, a striptease, the purchase of porn, or a peep-show. The choice was his, and either of which might have left him a little lighter in the pants, but not heading to prison. Only he didn’t. To his left was the Rupert Court Club at 8 Rupert Court. Not that he would have known this, as with no sign outside, the windows were covered-up and the sills were painted sills in deep reds and fleshy whites. But outside, stood a slim attractive brunette, whose job was the lure the young men in. The name of this raven-haired temptress was Maureen. Hot! Maureen Chapman. Hot! And with a few keenly-chosen words, this sultry siren said the words which Ted (and his balls) wanted to hear. Sexily, Maureen cooed “are you looking for a girl?”. Playing it cool, Ted shrugged “yes, it depends”, as if he was the one chatting-up her. So, having said “come in and I’ll talk to you”. With that, the deal was done and having been lured in by the simplest of cons, so was Ted… only he didn’t know it. At any point, he could have changed his mind, but part of the con is to make the punter feel bad about backing out or rejecting the lady. So, the second he stepped foot beyond the tall dark screen which shielded the world from its raw sexiness, he was in. This was the club… and it wasn’t much. It consisted of a single room, 10 feet wide by 15 feet long, being no bigger than a caravan. With a few red lights - as much to bathe the peeling wallpaper in an unsubtle sexy vibe as to disguise the stains - Ted was sat in one of several mismatched chairs; one which looked like it was once part of a patio set, one borrowed from a granny flat and one had blatantly been ripped out of a crashed Ford Zephyr. As to the left, a tacky velvet curtain sectioned off a tiny bar which was littered with watered-down drinks. Ted could have said “f**k this for a dingo’s dinky” and fled, but he didn’t. Being seated and with his bill racking-up, this is where their statements deviate. Maureen would state “I said to him ‘if you would like company, it’s £4 to sit and talk for a bit, or £8 for as long as you like’”. Although what heard her say was “she asked me would I do sex with her. I said “yes”. She said “it’s £4 for a short time or £8 for all night”. In a quick decision made using his other brain, more than half of his week’s wage was blown… and as he sat there grinning, he hoped that soon he would be too. With his cash, Maureen popped behind the curtain and handed it to her boss, having got Ted to hand over another £2 for whatever sundry bullshit they said was essential, and there he sat and waited. For fifteen minutes, they sat side-by-side and chatted politely with no touching, kissing and certainly no sex. The con is simple; the hostess never mentions sex, but the man assumes he is getting some. When he realises he has been conned, he has three options; leave having learned his lesson, get rough only to be turfed out, or call the police, except with no evidence, it would be his word against theirs. With his mates still waiting outside, Ted was already becoming impatient, when a familiar face walked in. With the two bobbies able to help, the agitated Chinese guy stormed in, barking in broken English that he wanted his money back. Ted would later state “I knew then that I had been taken for a fool”. As many men do, Ted demanded his money back, but Maureen explained “I can’t get it, it’s booked in and we’re not allowed to refund it”. Ted insisted, his face turning puce as his temper grew fouler. This was his money, he had earned it, and – although he had made the mistake – he hated being cheated. Seeing his mood grow black, to pacify him (as her boss had vanished), she agreed to meet Ted in about twenty minutes time for a coffee at the Golden Egg on Oxford Street. Unsure if he’d get his money back or his money’s worth, calling her bluff, he threatened her: “if you don’t turn up, I’ll come back”. And with that, Ted walked out. Martin would state “when he came out, he was silent but I could see he was in a flaming mood. I asked him what was the matter and on the third time he said ‘nothing’. He wanted to go back to the flat”. With their fun night out well-and-truly buggered, Martin drove them back to 87 Ridgemount Gardens; they climbed the stairs to his flat, and by the stroke of midnight, the boys were getting ready for bed. Ted could have gone to sleep, he could have let it go, or he could have brushed it off as a silly mistake? But he couldn’t. His pride was damaged, his tipping point was reached, and somebody had to pay. Half an hour later, the lads realised that Ted, his bag and Martin’s car were missing… …but by then, it was too late. At 12:30am, Ted sat waiting outside of The Golden Egg, its drunken punters stumbling into this late-night café to feed on a feast of foods all served with chips… but none of them were Maureen. (Ted) “I waited a few minutes till I was sure she wasn’t coming”, then he headed back to Rupert Court. Twenty minutes later, having dumped the car, Ted got out. Still seething; he didn’t lock it and he didn’t think, as fuelled by raw emotions, he stormed down Rupert Court. His walk quick and his eyes fixed, as across his heaving chest he clutched a blue and white bag emblazoned with a Pan Am logo. The alley was just as he had left it an hour before; the nauseating hum of neon, the crunch of broken beer bottles and the stale stench of warm piss, as outside two guys argued with a girl over money. Ted would later state “I pushed past her and said ‘I wanna see the other one’”. Barging her aside, she grabbed his sleeve and asked him to leave, yelling “get out or I’ll call the police”. But Ted was tired of asking nicely, he meant business, as from his shoulder bag he pulled out a little gift from the Land of Oz. Through the gloom, the girl screamed “help”, “call the police”, as in his tightening fist he held a 12-bore sawn-off shotgun. The alley erupted into blind panic, “help, he’s got a gun”, as with a swift bolt action he loaded a cartridge of No4 lead shot into the barrel, and stormed into the dingy dark-lit club. Inside, although one punter had fled, several sat in the battered car-seats, too terrified to move. Hearing the commotion, as Maureen came from behind the tacky velvet curtain, Ted stuck the barrel of the shotgun in her startled face, (Ted) “I want my money”. With his eyes wide and his teeth bared, there was no negotiation to be had, no bullshit about a refund policy, as Ted barked “I want my fucking money”. Maureen knew she had to calm him and comply – (Maureen) “relax, I’ll get it, just chill out”. As she went into the backroom bar, Ted followed, standing half-way between the tacky velvet curtain, with one eye on the hostess and one on the punters. To Ted, this wasn’t an armed robbery, as with him being the victim of confidence trickster, he was just getting back what was his – only quicker. Outside, the panic had reached fever pitch as excitable crowds jostled for a peek. With the bar as big as a bank of urinals, she only had to count out ten quid, but the longer this took, the more wound-up Ted got. “You’re stalling, hurry up” Ted barked, as he focused on Maureen and not on the door. Roy Martinson had been standing outside of the Two Decks club with his pal Sammy the Turk, when he heard a hostess hysterically screaming “some man’s trying to shoot my friend” and went in to help. Only half-believing her story, as Roy sauntered into the club, seeing only a flank of frozen men sitting silently on threadbare seats, Roy quizzed them with a knowing smirk - “alright then, who’s got a gun?”. From beyond the curtain, the angry Aussie drawled “I have” as he poked the shotgun’s muzzle in Roy’s chest. Stuck in a stand-off, the Aussie glared the local lad down, but Roy was not intimidated. Not in the slightest, as he chuckled “that’s a silly thing to do, I should put that away if I were you”. With both men pumping too much testosterone, as if to challenge him, Ted said “do you want it?”. At this point, their statements deviate; as Roy said “I took that to mean did I want the gun. I reached out for it”, Ted would claim “he had a look of surprise on his face and he grabbed for the gun. It went round in an arc as we twisted”, only Maureen would later clarify “there was no struggle, no fight”. Either way, from just two feet apart, the shotgun went off. With a flash of yellow, as a shockwave echoed the tiny room, Roy was blasted in the stomach. Doubling over, as his shirt pooled with a flowing crimson, he stumbled out of the club and collapsed in the alley. Snatching the ten quid from Maureen’s trembling hand, Ted fled the club. With his getaway car parked barely fifty feet to the left, and that side of this narrow alley blocked by a group of panicked people tending to a bloodied Roy, turning right Ted ran into Wardour Street followed by a small furious crowd. (Ted) “As I reached the footpath, somebody hit me over the head with a bottle”. Having heard the shot, Dinos Mayromatis, a kitchen porter and Petro Neophytou, a waiter, chased after Ted, as blood streamed from his head wound, pouring down his back, as they hurtled Gerrard Street. Three times Ted waved the shotgun at the two men, hoping to scare them, but they kept chasing him, hurling whatever they could, whether bottles, bricks or traffic cones, to stop him or slow him down. Passing Macclesfield Street, having grabbed a broom handle, Dinos would state “I tried to hit him with it and we came face-to-face. I was about 6 feet away, when he pulled out the gun and shot me”. As hot balls of speeding lead blasted into his face, neck and chest, as he slumped onto the cobbled street. So indiscriminate was the shotgun’s blast, that a single shot zipped 200 feet down Gerrard Street, and outside of Rupert Court, it hit Barry Glatz in the neck, as he chatted to a pal outside the Alphabet Club. Petro gave chase from a cautious distance, but he lost sight of Ted on Shaftesbury Avenue. With his victims rushed to Charing Cross Hospital, Barry had a single pellet removed from his neck and needed only two stitches, Dinos’s blast from six-feet away left only superficial wounds although he would remain partially sighted in his left eye, and - miraculously – although he was on the critical list and underwent an emergency operation to his stomach, having contracted pancreatitis and gangrene, Roy was discharged after six weeks. Thankfully, there were no serious injuries and no loss of life. (End). In the following days, Ted laid low and although the incident was in the papers, no-one knew his name. Ten days later, finding a shotgun cartridge under his bed, Brian McDonald (a room-mate of Ted’s pal, Ken Smith) realised the connection to Ted who was seen bleeding and had fled, and called the police. At 7:45pm on 3rd November 1967, Ted was arrested as he pulled the white Ford Transit into the garage at 9 Bristol Mews. Technically, he was on the run, but needing money, he was still driving the van. Taken to West End Central police station, Ted confessed to the shooting, bluntly stating his motivation “they robbed me of money and I lost my temper”. But when Detective Sergeant Hopkins asked “so why did you cut down the shotgun’s barrel with a saw?”, Ted’s reply was as Aussie as it gets – “I was going to use it for shark fishing… only I didn’t realise that, in this place, they are no bloody sharks”. The trial was held at the Old Bailey on the 19th and 20th February 1968, before Mr Justice Thesiger. Blessed with a sympathetic jury and having pleaded guilty to two lesser charges, he was found guilty of wounding and possessing a firearm. But on the charges of ‘grievous bodily harm’ and ‘shooting with intent to murder’, he was found “not guilty”. Ted was sentenced to a total of ten years in prison. After his release, Ted moved back to Australia and settled in Riverwood in Sydney; where he married, had several children and grandchildren, and he recently passed away in July 2020, aged 78 years old. For the sake of £10, a little kiss-kiss and a flash of bang-bang, three lives were ruined and ten years of life were lost. It may seem ridiculous, but then again, everybody has a tipping point. So, what’s yours? ** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London” and nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards".

0 Comments

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, all set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-THREE:

On the 14th March 1922, in a small ground-floor lodging at the back of 168 Hampstead Road, a baby girl was born. Conceived in secret by a young couple - 21-year-old Harry Gimber and 23-year-old Alice Crabbe - they hadn;t been able to abort it, the couldn't afford to keep, so having ran out of options, they decided to "abandon it". One week later, the body of a new born baby was found in Enfield, but with no way to identify Harry & Alice as the parents, its disposal should have remained a secret. So, what went wrong?

CLICK HERE to download the Murder Mile podcast via iTunes and to receive the latest episodes, click "subscribe". You can listen to it by clicking PLAY on the embedded media player below.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of 168 Hampstead Road where the unnamed baby of Alice Crabb and Harry Gimber was murdered is marked with a mustard coloured raindrop near the words Mornington Crescent. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

SOURCES: As this case was researched using some of the sources below. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/record?catid=5098213&catln=6 MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: Welcome to Murder Mile. Today I’m standing at 168 Hampstead Road, NW1; a few streets east and several doors south of Edith Humphries and Mabel Church, the first possible murders by the Blackout Ripper, as well as a deadly feud at Regent’s Park Zoo which saw a keeper bludgeoned to death - coming soon to Murder Mile. The Hampstead Road is a busy thoroughfare heading from Mornington Crescent to Warren Street. As you pass a set of flats and a brown bridge over the trainline into nearby London Euston, on this site once stood a row of three-storey Georgian terraced houses, which have long since been demolished. Crammed-full of dozers as Cross Rail decimates the city, it’s no surprise they’ve gone over budget as you never see a construction worker actually work. You might spy one wetting a bit of road with a limp hose or ten men ‘supervising’ as one man digs, but most of the time, all they do is eat. Go to any café and you’ll be blinded by lines of hi-viz vests all chuntering ‘oi oi’, ‘fakin ewl’ and ‘lavely cappa tea’. Sadly, as a vital part of any city, although progress erases the past, sometimes that’s not a bad thing. Back in 1922, on this site stood a three-storey terrace at 168 Hampstead Road. As a lodging house for those with barely a few pennies to rub together, in a small back-room on the first floor lived a young couple – Harry Gimber and Alice Crabb. Being too poor to marry and too selfish to think of anyone but themselves, owing to the consequences of their carnal lust, it was here that a baby was born in secret. Having gone to full-term, it should have been a joyous day as a new life was born by two lovers. Only being seen as little more than a side-effect of their sex, even before its birth, the child was unwanted. And although this little baby would only live a very brief life, it wasn’t loved for a single second. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide, and this is Murder Mile. Episode 163: ‘The Unloved’. The tragic tale of this little baby is truly heart-breaking; as it was unloved, unnamed and unwanted. Many may ask ‘how could anyone do something so horrific to someone so young and innocent?’ But it happens more often that you’d think, as even today, the most likely victims of murder are babies. Henry William Gimber, known to his pals as Harry was born in Islington in 1902. Given the cruelty he would inflict, you may expect me to impart you a story of hardship, violence and insanity? But I can’t. Like many young men, Harry was born into a working-class family who fought to keep a modest wage coming-in and the looming hunger at bay. They were good people who weren’t criminals nor wastrels. Mentally, he was just a very average lad, who wasn’t aggressive, moody or depressive. In fact, except for a grandmother who had died in the Hanwell Asylum owing to senile dementia, his family had no history of mental illness, and neither did he suffer any diseases or accidents - which could excuse this. At worst, he was immature and selfish. But find a young lad on the cusp of freedom who isn’t? Aged 14, Harry left school. Alongside his dad, he joined London Transport Company as an apprentice, but found the grit and grime of the railway wasn’t for him. In his teens, he still wasn’t sure what he wanted to do, so – although often working several low-paid jobs at a time – he flitted between many menial roles; whether as a waiter, a kitchen porter, a butcher’s assistant and a nightclub attendant. By his late teens - like many young men - Harry was desperate to move out of his parent’s house; to live his own life, to do his own thing and to finally become a man. Only, as we’ve all done, he still hadn’t got a grip on his responsibilities; like paying bills and rent, before buying treats and having fun. It was a big part of growing up which he was yet to learn. On the 20th March 1920, in Tottenham Court Road, 18-year-old Harry met 21-year-old Alice Crabb and the two fell in love. As a local girl born and raised in nearby Clement St Danes, although both parents were rarely home, she was raised under the supportive bubble of her grandmother and her niece. Living in a small lodging full of strong independent women who earned their own wage and ran their own household, it’s not surprising that – although society dictated that Alice could only follow one path in life, as a wife and mother – what she wanted was a little fun first and to enjoy being young. For Alice, marriage was not the be-all and end-all, and - with at least two decades of fertility ahead of her - she knew she had time to get a job, to live her life and to make her own mistakes, rather than being dragged kicking and screaming into the endless everyday exhaustion of cooking and cleaning. In April 1921, they began working at the National Orchestral Association at 14 Archer Street in Soho, with him as a doorman and her as a waitress – along-side her close friend, Dolly Oust. And having moved out of her parent’s home at 44 New Compton Street, Alice got her own lodging on Tottenham Street, where she could live as she saw fit. On 12th June 1921, Harry Gimber moved in… …and their relationship began. Harry Gimber & Alice Crabb were not bad people. They were two ordinary kids who were cursed with immaturity and a selfishness, and – some may argue –struggled in an era fuelled by the societal pressures of the morally upright and a series of cruel rules based on the law-maker’s religious beliefs. There is no denying that what they did was abhorrent… …but being little more than children in an adult’s world facing grown-up issues - even when a wealth of evidence stood against them - what we still don’t know is who was telling the truth? According to both Alice & Harry, it wasn’t until the first night together that they engaged in sex. Maybe they were careless? Maybe they didn’t know about contraception? Or maybe they cared little about the consequences? But that night, a baby was conceived - not out of love, but by mistake. In court, Harry would state “at first, I had no idea what to do. We were more or less astounded. We decided to make the best thing out of a bad job and get rid of it”. A feat which is easier said than done in an era where unwed sex was a scandal and abortions were illegal. But that’s when nature took over. In November 1921, being a little over five months pregnant, Alice suffered a miscarriage. Within their small lodging, she stifled her squeals to prevent her pain permeating the wafer-thin walls, as this slight girl gave birth to a cold lifeless child in the cramped confines of a communal bathroom. Not one of the tenants heard a sound nor saw a drop of blood, as their clean-up of the squalid toilet was thorough. Sadly, this was an all-too-common sight in an era when women were forced to give birth regardless of whether they were fit, well or could cope. Torn by the risk losing their job, home or family, most newspapers were full of stories of young unwed girls who had abandoned their babies in secret; whether in churches, doorways or bushes, in the hope they’d be found before succumbing to the cold. For many women, this was a desperate time. But for Alice & Harry, this wasn’t a life they held in their hands, it was a liability. And with the 10 inch long, half-formed foetus lying dead in the base of the bowl, they spoke of its disposal with the cold callousness of someone who didn’t care: (Harry): “I threw the miscarriage down the lavatory. Neither of us told anybody about it”, as this half-pound lump of life was flushed away like human waste. Of course, this may seem sad, but Alice’s miscarriage was a lie… …and it was one of many lies they would tell to hide the awful truth. By January 1922, Alice was seven months pregnant. It was winter, so hiding her bump wasn’t difficult, but reduced to a wage of just £1 and 10 shillings a week, they were lucky to have fivepence to spare. Unable to ask their parents for help, Alice & Harry moved into a small one-roomed lodging at the rear of 168 Hampstead Road. Being roughly 10 feet square – a space smaller than a prison cell - it had a horsehair bed, a tiny wash basin, a little fire and a small table for meals, but no kitchen or bathroom. It wasn’t much; but it was cheap, the landlady (Mrs Birch) bothered them just once a fortnight to wash the bedsheets, and – having been built on top of a busy trainline - the rumble of trains hid many sins. Being desperate, they had hoped for a miscarriage, but it was not to be. Being broke, they couldn’t procure a black-market doctor who could bring about a swift solution with a bottle of bleach, a coat-hanger and a high risk of infection and maybe death. So instead, they had to rely on quacks and tales. They had tried it all; everything from hot baths to neat gin, heavy lifting to icy swims, vigorous walks to (the new wonder cure) castor oil. An accident was a cheap option, but a punch to the gut or a fall down some stairs risked her own life. And even the tried-and-trusted purgatives like Penny Royal and Ergot only made her sick. So, with the baby just eight weeks away, they were running out of options. At the end of January 1921, with just six weeks till the birth, while working one of his jobs as a kitchen porter, a waitress called Grace heard his tale of woe and said “you ought to see my sister”. That night, Alice, Harry and Ada Cook met in a pub in Chalk Farm. They sat quietly and chatted in hushed tones about the best way to “flush it out”, and although Ada could help, she said “it won’t be cheap”. And it wasn’t. For a few capsules in a plain box, a bottle of an unknown liquid, a syringe, a funnel and a hand-written list of instructions, it would cost £4 - more than Harry earned in a single month. This was their last chance… but it failed. With Alice now eight months pregnant, their only option was to give birth. But then what? No-one knew about the pregnancy, not their families, friends nor landlady. In court, Harry would state “we agreed that should the child be born alive we were going to get rid of it by abandoning it”. When asked “what do you mean ‘abandon’?”, he admitted they hadn’t made plans to put it up for adoption, but that “we thought we’d knock and leave it on a doorstep”, denying his plan was to “leave it to die”. Quizzed by the prosecution, when Alice was asked “had you not arranged to get rid of it somehow?”, she would state “no sir, I would have kept the child but Harry did not want to”. Only this was a lie, as when asked “what preparations had you made?”, she had to admit “none sir, none whatsoever”. For the baby’s arrival, there was no food, no clothes, no toys and no crib. Conceived by accident and to be born in secret, the little baby was doomed to die in silence and to be disposed of by stealth… …as the only preparations her parents had made for her brief life was a few sheets of brown paper, a set of sharp scissors and a ball of string – these were the tools they needed to dispose of its body. On Saturday 10th March, with Alice’s bump too big to hide, her disappearance was excused with a lie. (Harry) “she twisted her leg, catching her heel in the tram lines on Hampstead Road, and was confined to bed for a week”. It was a tall but believable tale they would tell the landlady and (later) the police. Three days later, on the morning of Tuesday 14th March, Alice’s labour pains began. Sat silently in their small dingy room, although she wanted to scream as the afterthought inside her pulled apart her tiny pelvis - to disguise their dirty deed - they spoke only in hushed whispers. “It’s coming, Harry”, “right, what do I do?”, “I don’t know”. Without a midwife or mother present, these novices had no knowledge nor skills to cope with what would happen - whether they liked it or not. As her pains grew more powerful, Alice bit into her pillow to muffle her screams, only daring to expel an audible squeal as the trains roared by, without the fear of being caught by those in the next room. The baby was coming. Only they weren’t ready for a birth, they were ready for a death. As across the small bed where Alice lay, digging into her stretched and sweaty skin was the uncomfortably sharp crinkle of sheets of thick brown paper, a quick fix to soak up the blood which they landlady might see. At roughly noon, she knew it was time (Alice) “Harry, it’s coming out, I know it is, I can feel it’s head”. Shuffling to the foot of the bed, dressed only in her nightdress, Alice stood upright; sweaty incessantly as her pale knuckles tautly gripped the metal bed-frame. Breathing hard but keeping silent, as the top half of its head stretched her vagina wide, with tear-sodden eyes and gritted teeth she hissed at Harry “don’t fail me, don’t fail me”. Although, quite what she meant by that, we shall never know. With no witnesses, there were two possible ways that the baby was born. Alice’s way: (Alice) “I was standing by the bed. The child was born. It fell onto the floor”. With no-one to catch it, having fallen head-first onto the hard wooden floor, her defence was that a two-foot drop had shattered its skull – which is plausible. Only a pathologist would note; “the bones of a new-born are not fused and the skull is soft, so it may have rendered the child unconscious, but it did not kill it”. In court, Alice described the moment for the jury: “it was lying on the floor, I could see it, it was a girl, she was small”. But as much as she would play the grieving mother, the evidence told a different story, as never once did she pick it up, comfort it or cuddle it, she just let it lie there on the cold hard floor. And then there was Harry’s way: (Harry) “…when I saw the kiddie coming out, I made a grab at it and caught it by the neck. I held it hard because it was greasy and when I was hanging on it, I pulled it very hard and it went limp. As soon as it went limp, I started to tremble and dropped it on the floor…”. His defence being that he was frightened and inexperienced, not that he was cruel and wanted it dead. It’s possible that both births could be true, just as both could be lies. But then again, an autopsy would find no evidence of a fractured skull, a brain haemorrhage or a broken neck. And again, neither of its parents showed any compassion for the little baby girl which lay at their feet. All they could think of was their own lives, own jobs and own future now this little problem was gone. With it out, Alice got back into the bed covered in brown-paper, to rest and deliver the afterbirth, as Harry: “no sooner had it dropped, I thought to myself the best thing was to get it out of the way”. Only, if the baby was really dead? Then why they do what they did next? Alice would state “I was standing by the bed. I was conscious. I saw Gimber put his hand round it’s throat and try to strangle it. I asked him not to” - a statement which Harry would vehemently deny. But with this new-born baby still covered in the vernix caseosa – a greasy second skin which protects it in the womb - being too slippery to grip its throat, it’s likely that Harry chose to strangle it by ligature. Harry: “she gave me the bootlaces to tie around its neck” – a statement Alice would deny. But then again, although an autopsy would find both manual and ligature marks as well as a boot lace around its tiny neck, with no witnesses we only have their vague recollections as to what happened that day. And although an attempt to strangle it was made… that was not what killed this unnamed baby. (Alice) “He took a knife off the table”, at which Harry decried “that’s not true”. A large kitchen knife roughly six inches long. (Alice) “I saw him pick it up and put it to it’s throat”, which Harry protested “I never touched it, I didn’t”. And although he would shout “that’s not true” to all of her statements, in court, Alice would deal the fatal blow to his defence by stating “I saw him cut the child’s throat”. And as if to tug at the jury’s heartstrings, she would state “as he did it, I heard the child whimper”. Which begs the question; how could the child whimper if it was unconscious, and why were its tiny little lungs still half-full of amniotic fluid, as if she had barely had a chance to take her first breath? The timings made no sense. After its death, as Alice rested on the crinkled paper, Harry set about cleaning up, although “I can hardly remember what else I did”. But thankfully – unlike Alice & Harry - the evidence would not lie. Having folded the pale lifeless baby into a foetal position, this tiny ball-like bundle was wrapped in brown paper, tied up with string and stuck in a cupboard - out of sight, out of mind, out of conscience. Once the afterbirth was out, he washed the floor with a bucket of water, he disposed of the brown-paper bedsheets, and at the little dinner table beside the cupboard, the two ate eggs, then she slept. At 7pm, she was awoken by burning, as their small fire consumed all of the evidence, and the almost familiar smell of cooked liver emanated their tiny room as the child’s afterbirth burned in the grate. At no point, in any statement, do they admit to feeling guilt, upset or remorse for the baby… …only themselves. At 6pm, Harry took the parcel out of the cupboard, “I got on a tram to Lordship Lane in Wood Green. I know the district well. I got half way down, I went along the side street to Five Oaks. I dropped it in a ditch, then I got on a tram and returned home” - in a disposal which he said “was mutually agreed”. And that was it - their baby was dead, dumped and forgotten. On Saturday 18th March, four days later, 9-year-old Stanley Mathers was playing with a piece of wood on the water. Popping his pretend sailboat into a drainage pipe, “when I put it in, it usually came out, but it did not. I looked inside and saw a small wet parcel… a piece was torn and I saw a very small ear”. Examined by Dr Robinson Dixon, she had been dead for several days. With a bootlace around her neck and no other obvious injuries, death was caused by “a cut across the throat from one side to another… a very deep gash right down to its spine, and although the knife was very sharp and the child’s tissue was very soft, the cut was v-shaped, as the two cuts joined causing three gashes to the spine”. With no way to identify this abandoned child, a hushed inquest was held at Wood Green Coroner’s Court, which determined that the unnamed baby was “murdered by person or persons unknown”. The case was closed, the evidence was destroyed and the child was forgotten – loved by no-one. This was the dark little secret which Harry & Alice would take to their graves… …only a secret can only remain silent if both parties stay quiet. Three weeks after the murder, they moved out of 168 Hampstead Road and a new couple moved in. For the next six months, they shared several lodgings in Blackfriars, Westminster and Warren Street. Only the pressure of hiding such a dark secret inside them had taken a serious toll on their relationship. They argued at home, they fought at work, the screamed in the street, and - with their love affair now in tatters – behind Alice’s back, Harry had started seeing someone else – their close friend, Dolly Oust. On 17th October 1923, seeing Harry in Old Compton Street, Alice began throwing accusations at Harry and Dolly, as much to hurt him as to ruin their relationship. Out loud and in public, she accused Dolly of being pregnant, of being a whore, and of Harry murdering and disposing of their unwanted baby. With nothing else to lose, Alice dragged Dolly, followed by Harry, to their former lodging house at 168 Hampstead Road and expelled the whole sorry story to the landlady – Mrs Birch. They did the same at the abortionist Ada Cook’s – none of whom wanted anything to do with them – but with Harry in denial and Dolly all defensive, with no evidence to prove it, Alice’s words just sounded empty and sad. But then again, to quote William Congreve’s ‘The Mourning Bride’ – “Heaven has no rage like a love to hatred turned, nor Hell a fury like a woman scorned”. Two days later, upon hearing the news that Harry & Dolly had been married at Brixton Registry Office, Alice Crabbe went to the police. (End) At Albany Police Station, Alice confessed, in a way which made her as much of a victim as the baby. Although in court, she would admit that her motive wasn’t justice for the baby, but jealousy and spite. She blamed Harry for the death, the disposal, and said he had blackmailed her into keeping it a secret. Harry Gimber was arrested on 20th October, the day of his honeymoon, and gave a statement which – like Alice’s – was as vague as it was convenient. In it, he denied strangling or slitting the baby’s throat, but confessed to everything else – making him guilty of conducting an unlawful burial, but not murder. The trial began at The Old Bailey on the 4th December 1923 before Mr Justice Avery. On the charge of murder, Harry pleaded ‘not guilty’ and although ‘an accessory’, Alice only appeared as a witness. For the jury, the trial was indeed a trial, a trial of their patience; as Alice came across not as a grieving mother as “her arrogance and lack of compassion shone through”, Harry’s memory remained vague and he repeatedly littered his abusive curses with slang which (not only confused but) annoyed the court, and the judge was so old and deaf, that every statement was suffixed with “what did he say?”. And yet, through all of Alice & Harry’s bickering from the dock, it was thanks to the expert witnesses that a conclusion was reached. Having retired for half an hour, on 14th December 1923, Henry William Gimber was found guilty and sentenced to death, but this was later commuted to a life sentence. Alice Crabb was neither convicted nor tried for any offence, and she was released. And as for their unnamed, unplanned and unloved little baby? She remains buried in an unmarked communal grave. ** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London” and nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards".

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, all set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-ONE

This is Part Three of Three of 'Do Not Disturb', the untold story of the murder of Sarah Gibson. In the summer of 1972, 21-year-old Sarah Gibson worked as assistant housekeeper at the RAC Club at 89 Pall Mall, London, SW1. She was quiet, pleasant and she kept to herself. Those who knew her had nothing but kind words to say about her, but on across the night of Sunday 2nd to Monday 3rd July 1972, not only would a sadist assail this veritable Fort-Knox of security and navigate its maze of corridors to access her room, but they would subject this young girl to a truly shocking attack over four torturous hours, which ended in her death. But why?

CLICK HERE to download the Murder Mile podcast via iTunes and to receive the latest episodes, click "subscribe". You can listen to it by clicking PLAY on the embedded media player below.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of The RAC Club in Pall Mall where Sarah Gibson was murdered by David Frooms. It is marked with a mustard coloured raindrop near the words Charring Cross. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

SOURCES: As this case was researched using some of the sources below.

MUSIC: