|

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, all set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE TWO HUNDRED AND SEVEN:

On Wednesday 21st December 1853, 27 year old Hannah Heisse, a married mother-of-one gave birth to a baby daughter, later to be joined by her husband, a 34 year old tin plate worker called Bertolt Heisse. For three days, being cared for by Bertolt and her mother, Hannah rested as this prolonged birth had left her weak. It should have been the start of a new life for this beautiful little family. But owing to a little thing called jealousy, on Saturday 24th December 1853 (Christmas Eve), Bertolt (her loving husband) would unleash a bloody massacre and destroy this whole family forever. But why?

CLICK HERE to download the Murder Mile podcast via iTunes and to receive the latest episodes, click "subscribe". You can listen to it by clicking PLAY on the embedded media player below.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location is marked with a teal exclamation mark (!) below the words 'Shaftesbury Avenue'. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, click here.

MUSIC:

Welcome to Murder Mile. Today I’m standing on Shaftesbury Avenue, W1; one street north of the killing of Soho king-pin Red Max Kassel, one street south of the brutal slaying of Dutch Leah, a few doors east of the fatal seizure of James McDonald, and three streets south of the striptease of death - coming soon to Murder Mile. Today, Shaftesbury Avenue is the supposed home of the West End show, but with very few new plays to warrant its nickname, Theatreland is little more than a slew of pointless pap; where faded pop stars crowbar six hits into two-hours of tenuously linked drivel, tired 1960s farces called ‘Oooh Err Missus’ feature two repugnant horn-dogs opening and closing doors until the hinges (and their knickers) fall off, and – for the truly vapid - movies remade for the stage. So expect to see, a rom-com of Schindler’s List, Top Gun the drag-act, a Busby Berkley version of Amistad, and – as the final nail in the coffin, as Disney has truly suckled this withered teat dry – a kitchen sink drama about the Marvel multiverse. And yet, had anyone opened their eyes, they’d have seen that the real drama was on their doorstep. Demolished to make way for Shaftesbury Avenue, back in the 1850s King Street consisted of two lines of three storey terraces, crammed with semi-skilled working-class labourers, whether tailors, painters and tin pot makers. On the top floor of 15 King Street once lived Bertolt Heisse, his wife Hannah, her toddler daughter and soon, a new baby. It should have been the happiest of times for this little family… …but unlike a funny little farce about infidelity, a lack of trust would lead to tragedy. My name is Michael, I am your tour guide, and this is Murder Mile. Episode 207: A Jealous Streak. Triggers. We all have our triggers, those little ignitions of our dormant thoughts and our uncontrolled emotions, which can make us smile, can make us cry, and – if pressed too far - can make us snap. His full name was Bertolt Theodore Heisse, a 34-year-old native of an unspecified town in Germany. With no known relatives in England, let alone in London, why he came to Britain is uncertain, but since then he had lived an unremarkable life on the borders of Soho and Haymarket for at least four years. We know little about his life, and had it not been for his callous crimes, he would have been forgotten. What’s most vexing is that Bertolt wasn’t a bad man; he worked hard, he didn’t break the law and he wasn’t a layabout, a loafer or a lout. He was just an ordinary man who refused to see his own faults. Described as professional but sober, since his arrival, Bertolt had been employed as a master tin-plate worker at Messers Farwig & Bullock of 16 Rupert Street, just off King Street. Being a semi-skilled man in an in-demand profession, he would fashion sheets of tin into all manner of household essentials, such as kettles, saucepans, canisters, milk pails, lamps and lanterns, using shears, hammers and solder. According to Walter Bullock the co-owner, Bertolt was well-liked and well-regarded, being a reliable man who was never late, never unruly and prided himself in the quality of his work. Always a neat man, he liked his life to be as orderly as his appearance, with clean hands, short hair and a tidy beard. He was sober in character and in drink as he rarely drank, and almost never got drunk. But he was not a solitary figure, a friendless sort, or someone others disliked, he was just as ordinary as anyone else. Sadly, we know little about his love live, whether he was ever engaged, previously wed, a gay bachelor, a grieving widower, or was simply a singleton who was in and out of love like an eternally jilted Romeo. Described as tall, dark and handsome, Bertolt had no problem attracting the ladies… but that was one of his faults – it wasn’t the single women who wooed him who he wanted, but the married ones. As a lover of other men’s wives, he openly flirted with any filly who took his fancy, it is said he engaged in tawdry affairs with any attractive woman who caught his glance even for a second, and – even when shopping for basics like bread – he couldn’t help but slather a sexy stranger with his smoothest words. Obviously, as a lothario who preyed on those in loveless marriages, there are no records of his illicit affairs or who with, so we can only speculate. But as much as he only thought of himself and his carnal lusts, he never set aside a single iota about the fall-out from his dirty little dalliances with an already-wed woman he had wooed into bed – not her husband, her children, her life or the aftermath. Thomas Chater, who also lived at 15 King Street would state “he was very fond of other men’s wives”… …which was ironic, given his little issue. It’s unsurprising that Hannah, his future wife was described as ‘an attractive lady’, a real head turner who made men draw sharp breaths, with a gaping mouth, a widening of the eyes, and causing a slight shift in how they sat, often crossing their legs for fear of their lower half mustering a ‘moral outrage’. 27-year-old Hannah Hodgkin was from Spalding in Lincolnshire in the east of England. As one of several daughters to a family of farmers, she had come to London (possibly) to start a new life where her past would never be known, being an unmarried mother to two toddlers, one of whom had recently died. Travelling 140 miles south from the remote wilds to the bustling throng of the big city must have come as a shock for Hannah, but gripped with grief and fleeing her pain, she arrived with nothing but a bag of essentials and her toddler daughter, in search of paid work, a nice home and hopefully a husband. Bertolt was an obvious choice for Hannah; a tall handsome man who was neat in both life and in style; a sober professional who (as a steady worker) could provide her with everything she could ever want; and as a lover would give her whatever she desired and take on the child of a man he had never met. In January 1853, at a nearby church (believed to be St Ann’s in Soho), Hannah Hodgkin married Bertolt Heisse, in a small service attended by her family, but not his, having no known relatives, until now. For Hannah, this was the start of a new year and a new life with a new husband. Being neither rich nor poor but financially comfortable given his steady income as a semi-skilled craftsman, shortly after their marriage, Mr & Mrs Heisse moved into the front attic rooms in a three-storey terrace at 15 King Street. It was a decent lodging house owned by Mr Powell, a local baker, and occupied by several tradesmen and their families, some of whom Bertolt knew. Entered via a communal street-door, at the top of the wooden stairs, the Heisse family lived in two rooms; a kitchen/sitting room and small tidy bedroom. For Hannah, it must have seemed like a dream come true; a happy marriage to a man she loved, a little toddler who was healthy and happy, a nice home to live in and enough money to be comfortable. At that point, her life was perfect… …until something changed everything. Bertolt loved the ladies. That little fact about his wandering eyes, his creeping-hands and his ardent loins which longed to stand proud before a butt-naked beauty who was already betrothed to another bloke was well known. Whether - whilst married to Hannah – he ever dipped his wick in another man’s inkpot is unknown, but his thoughts were never far away from his beautiful new wife… and her fidelity. He never saw the irony of his actions, as when he flirted with women, it was just a bit of harmless fun; but when she dared to look at other men, or if they dared to ogle his lovely wife, Bertolt would fume. Jealousy pervaded his every waking day and haunted his dreams, as he lay beside the woman he loved. As she slept soundly, he wondered which man it was she dreamed of, never thinking it could be him. As she dressed for the day, he questioned why she looked so pretty, why her perfume was so pungent and always checked to see if her ring was still on her finger, having had it placed there by God himself. In his mind, adultery was the ultimate sin, but only if this sin was committed by her, and not him. Even the most ordinary of days could illicit his irritable temper, as simply walking along Berwick Street market shopping for the basics, his ire would rise as his eyes maybe saw – what he believed – was her licking her lips too often, her hips to close to a man’s, her hands fondling fruit too suggestively, and a predatory wife-snatcher prowling these civilised street looking to pounce on his stunning young bride (as decreed by the law) and thus, ruining his perfectly good marriage, owing to a lothario’s carnal lusts. At home, he would watch her, by keeping one eye open for any sign she was having an affair; whether a new dress, a racier shade of lippy, a crinkled bedsheet, or an extra cup in the washing-up bowl. But at work, it was worse, as plagued by a possessive streak of jealousy, all he could think about was her. A small change became obvious to Walter Bullock, his boss at Messers Farwig & Bullock a few months after the marriage, as sometimes – not often – Bertolt’s punctuality and professionalism began to slip, as instead of worrying about the solder on his tinware, he was focussed on who his wife was shagging. There was no proof she was unfaithful, but once that seed was planted, it could do nothing but grow. And yet, it was that seed and the suspicion… …which changed their lives forever. The summer of 1853 should have been a truly happy time for this little family; the weather was good, their home was fully-furnished, and a swelling in her womb told Hannah that she was pregnant. Like a special little gift for both parents, this baby would be born either on or near to Christmas Day. By all accounts, Hannah was ecstatic with joy and now their family would be complete. But Bertolt was not. As a jealous man who trusted her about as much as any man could trust him with their wife, although he had no evidence of an affair, a boyfriend, or any sex out of wedlock, he couldn’t be certain if the child was his; in the same way that some men who he no longer spoke to said the same of their child. When told of her happy news, his face was blank and his mouth grimaced, as his mind raced to work out who – outside of himself – the father was; and with that, he would taunt her with his suspicions. As her belly grew larger, the greater he grew distant with his wife and her unborn baby. Whereas once, each morning he would kiss her, now he would barely grunt her a ‘good morning’, as while she slept, he couldn’t help but think of who had been inside his home, inside his bed, and even inside his wife. Her swelling wasn’t a symbol of their undying love, but an incessant reminder of her possible infidelity. Her belly wasn’t a countdown to family contentment, but a ticking timebomb to the moment of truth, as it would only be when he held the baby in his hands that Bertolt would know if the child was his. Until then, he felt nothing for her, or even for ‘it’. Every time she twinged; he felt no pains of sympathy. Each time she was sick, all he felt was utter repulsion at the thought that ‘this thing’, this ‘spore’ was most likely conceived by another man’s seed spat-out in an immoral act of filth between her and ‘him’. At some point, they stopped sleeping together, as Hannah and her infant daughter took the bed, and an almost silent and motionless Bertolt made a bed in the sitting room. Feeling unwelcome in her own home, until the birth proved her right, she couldn’t move out as her money was his, as was their home. Until that day, Hannah would do what would come naturally, by building a nest for her brood; a little bowl, a woollen shawl, a wooden crib, and some soft toys for this baby she would love no matter what. But the more reminders he saw of this off-spring which (most likely) wasn’t even his, the less he would contribute to its impending arrival; he paid the rent and gave her money for food, but nothing else. And the bigger her belly got, the nearer the day of reckoning would come, the more unkind he became. Described by his neighbours as a man with a short fuse and a violent temper, those who heard them quarrel said it never lasted long and it was rarely physical. And although he would never hit her… …once he had shaken this pregnant woman hard. By November, with Hannah’s bulging bump being a perpetual reminder of what happiness or horror was to come, Bertolt’s work at the tin-plate factory was becoming inconsistent and sloppy, as his mind wandered, his hands trembled, and – even amongst his colleagues – he became ratty and ill-tempered. He couldn’t eat, he couldn’t sleep, and he couldn’t think about anything except who the father was. At work, of the men he once trusted, he thought “is it him?”. Of any stranger in the street, he posited “perhaps it’s him?”. In his tired and fevered mind, he interrogated himself “is it a friend?”, “was it an ex-lover?”, “could it be a tenant at home, or someone I don’t know?”, “or maybe, it was the man who looked at her all those months ago on Berwick Street?”, as now, every smile was deeply suspicious. It was the ‘not knowing’ which was driving Bertolt crazy. By December, with barely three weeks to go, the only way to know was for the baby to be born, until then, he’d have to wait, and wait, and wait. Two weeks before, he would confide to a colleague, that if the baby wasn’t his… …“I would cut her throat”. As autumn gave way to winter and his sullen mood was replaced by an irritable temper, Bertolt had bought a spring knife with eight-inch blade. With the moment of truth almost upon them, his decision would be simple; if it was his, she would live, but if not “we should go off together in one bloody bed”. On Wednesday 21st December, in the attic room of 15 King Street, a baby was born. Ghostly pale and drenched in sweat, Hannah had done something miraculous in an era when 1 in 150 women died in childbirth. Sat slumped in a mattress bathed in blood, her labour was so prolonged she had barely enough strength to cuddle this bundle of joy, but just enough energy to smile, as this pink podgy mass of flesh gurgled at his adoring mum – a healthy little boy, with ten fingers and ten toes. The second miracle was that Hannah had done this all alone, as having sent her mother (Mrs Hodgkin) a letter and some money to travel down, she had arrived too late to aid her, and Bertolt was at work. At his usual hour, with no sprint in his step having been told of the birth, Bertolt arrived at his home. In his hands, he didn’t carry some flowers or a toy, and his face was far from the epitome of joy. Up the stairs he lolloped like a condemned man climbing the scaffold to his own death, which in truth, he was, only it wouldn’t be just her maternal excretions which would bathe the bed red that night. Setting foot in his room, he saw his wife, on his bed, holding her baby. She smiled hoping her joy would be infectious, only his face was as cold and hard as marble. The moment of truth had finally dawned, as with scrutinising eyes pressed into a harsh squint, Bertolt gazed upon the little sprog before him; examining its eyes, its hair, its face, its hands, to see whether it looked like him, and whether it didn’t. We have no record of what the baby looked like, but Hannah’s mother would state “he shook his head and simply said ‘enough, enough’”. Although what he meant by that will never be known. Moments later, he covered his shivering wife in warm bedclothes and whispered in her ear something unheard. The day was Saturday 24th December 1853, Christmas Eve. Across King Street, a mattress of icy snow carpeted the cobble-stone streets, a grey sky was blanketed in a thick sooty haze of burning tinder, as the soothing smell of roast chestnuts stained the air. It wasn’t Christmas as we would know it today, but across the land, they celebrated the birth of a little boy. Still weak after her herculean ordeal, Hannah mostly slept clutching her baby, as her mother and even Bertolt (who had taken a day off work) busied the house and readied the food while she rested. Mrs Hodgkin would state of her son-in-law “he seemed very kind”, which surprised her, given how Hannah had described him in her letters, and yet, Bertolt showed no anger towards his wife or child. At 7pm, as Bertolt felt the need to “purchase some necessaries for the child”, he escorted Mrs Hodgkin not to the less-salubrious Berwick Street market in Soho, but over to Grafton Street in Mayfair. A much longer walk, but well worth it, being a well-to-do area where the society elite would shop and eat. Having trudged for twenty-minute through the snow, although a little pooped, Bertolt decided to treat Mrs Hodgkin to tea and buns in a teashop off the Burlington Arcade, warming their toes by the fire, as a band of merry mistrals played a festive tune. Like the logs set in flame, she had warmed to him. Bertolt seemed like the perfect son-in-law, as he popped off “to get Hannah something special, I’ll only be but a minute” as he left the one woman who could have saved her alone. Mrs Hodgkin’s words would haunt her forever, as she replied – “mind you do, or I shall never find my way back again”… …but then again, that was the point. At roughly 8:57pm, Bertolt arrived at King Street, not ambling in a slouched saunter as he had when he heard that the baby was born, but his feet fixed with a determined sprint, as he bolted upstairs to his room, where his wife, lay on his bed, with her bastard baby who was born to another man’s seed. Bursting open the wooden door to the front attic room, upon seeing his supposedly cheating wife - it didn’t concern him that her toddler lay playing at her side, that Hannah was still bruised, swollen and bleeding from the strain of childbirth, or that this one-day-old baby was quietly suckling at her breast – all he saw was rage, as he started stabbing at her with feverish hatred with his eight-inch knife. As any mother would, with her instincts to protect, the left-hand side of her body took every piercing stab and slash as this weakened woman shielded her baby in her bleeding arms. Knowing though that she was no match for his blade, she screamed “murder!” as this limp lady stumbled from the room. With her terrified toddler clutching at her mummy’s leg, Hannah staggered onto the landing, her once white nightdress now sopping wet with thick red rivers from her neck to her legs. Seen by candlelight, and said to be “a shocking sight”, Mr Lloyd, a quick-witted neighbour carried her, profusely bleeding, to the safety of his ground-floor room, where on a sofa “her strength failed her”. With the door locked, she was safe, and her child was safe… but in her haste, her new-born baby had slipped from her grip. All the way down King Street, his panicked words were heard screaming “Fetch a doctor!”, “Call the Police!”, and with PC James Vener patrolling nearby Nassau Street, help was there within a minute. But by then, it was too late. Aided by PC Vener, Dr Robert Martin of Frith Street entered the silent attic with trepidation. Inside, it was still. On the bedside table, the eight-inch blade still dripped as thick red globs oozed freely. Said by the doctor to be “a frightful scene”, the floorboards pooled with a never-ending sea of blood. And with the sheets soaked thick, steam rose as the hot blood mixed with the cold winter air blowing in. From the gaping wound in his neck, gurgling was heard, as across the bed, Bertolt lay. With his own blade, he had slit his own throat from ear-to-ear. Described by the shocked doctor: “all blood vessels were cut, every nerve severed, and – slitting across the larynx - both carotid arteries and jugular veins were ripped”, as having thrown himself in pained agony back onto the bed, “having sliced right down to the bone, it was only the cervical vertebrae which had prevented his head from falling off”. It didn’t take a medical man to confirm that Bertolt Heisse was dead. And yet, this room still held one more terrifying sight. At first, neither man had seen it, until it blinked. As among the sodden sheets, it was only when its blood-soaked lids opened wide and the whites of its eyes were seen, that the baby was found – silent, shocked, but with not a scratch on its body. (End) Along with her toddler and her baby, Hannah was taken to the Cleveland Street workhouse where she was attended to by the surgeon, suffering several stab wounds to her face, arm, shoulder and chest. Three days later, an inquest was held in the vestry room of St Ann’s church in Soho (where it was said that the happy couple had married a few months before). With his wounds self-inflicted and his wife’s wounds a deliberate act of attempted murder (as Hannah still clung to life), after much deliberation, the jury returned a verdict “that he had destroyed himself while in a state of temporary insanity”. For several days, Hannah was attended to by doctors who described her as “being in a low and weak state”, and although – by New Year’s Eve - her mother said she was “progressing well”, a few days into the New Year, Hannah Heisse, a recently widowed mother of two, had succumbed to her injuries. With her body too weak having only just given birth, although those stab wounds weren’t all that deep for such a young and healthy woman, her blood loss was too great, and her strength was too little. There is no record of what happened to her toddler and her baby. Had her family adopted them, they may have stood a chance albeit scarred for life, but left to the workhouse, their fate would be sealed. Bertolt Heisse lived his life loving other men’s wives, he had no qualms about the families he ruined or the conflict he had created, just as long as he could fulfil his own carnal needs. But when the tables were turned, and his own paranoia took hold, lives would be lost… owing to his little jealous streak. The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of.

0 Comments

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25.

EPISODE TWO HUNDRED AND SIX: This is Part Ten of Ten of The Soho Strangler. At the crime-scene of ‘French Marie’s murder, the culprit had left his fingerprints. At the pub and a nearby market, he was seen with the victim, just hours before ethe murder, by at least twenty eye-witnesses, some of whom he had spoken to, even giving them details about his life. As the case stalled, once again, a strangler had vanished into thin air, and the murders would stop… …but only in Soho. 300 miles north of London, another murder and an attempted murder or two prostitutes in very similar circumstances would lead the Police to a very likely suspect in the murder of French Marie. But was he The Soho Strangler?

CLICK HERE to download the Murder Mile podcast via iTunes and to receive the latest episodes, click "subscribe". You can listen to it by clicking PLAY on the embedded media player below.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location is marked with a purple exclamation mark (!) above the words 'Euston Square'. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

SOURCES: This case was researched using some of the sources below.

MEPO 3/1722 - https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1257764 Murder, reduced to manslaughter, of Elsie Charlotte Torchon by Robert Dixon alias Norman Stephenson at Euston Road, NW. on 16 August 1937. STEPHENSON, Norman: at Durham Assizes on 25 February 1939 convicted of manslaughter; sentenced to 10 years' penal servitude; at Central Criminal Court (CCC) on 25 April 1939 convicted of manslaughter; sentenced to 16 years' penal servitude concurrent. PCOM 9/2030 https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1353018

MUSIC:

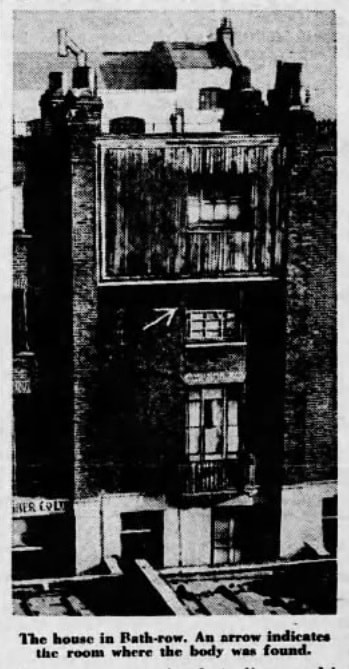

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: The investigation was led by Chief Inspector Drewe of the CID, who had overseen the murders of ‘French Fifi’, Marie Cotton, ‘Dutch Leah’ and ‘Red Max’, and would confirm “this is a case of murder”. As before, there was no struggle, robbery or assault. With a timeline of events as clear as the day itself, the evidence as irrefutable as dust, and an embarrassment of eyewitnesses (who had seen and spoken to her killer face-to-face from a few inches away), there was no mystery as to who had murdered her. A composite description was compiled by witnesses, which would perfectly match the man they would convict of killing Marie. He was “aged 24-30, 5 foot 3 to 4, thin to medium build, a roundish pasty face, a ruddy complexion, blue eyes, brown brushed-back hair, a dark brownish scruffy suit and no hat”. That same man was seen with the victim at the Adam & Eve pub, at Seaton Place market and then, at 4pm, both were seen by the tenants of the building entering her second-floor flat at 306 Euston Road. Dr Alexander Burney confirmed by in-situ examination that her time of death was “4pm to 5pm”. Eva & Kaufman Shladover living one floor above saw that same man from their window “walk into Bath Row and into Euston Road” at roughly 5:30pm. And no-one was seen to enter or exit her room, until at 6pm, as established by the Scent factory whistle, when they extinguished the fire and found Marie. With the police report stating: “…the victim was a woman given to drinking and prostitution… there is no doubt that the murderer was a chance ‘pick up’ in a public house”, the evidence was irrefutable. Without doubt, her killer was a man she trusted; having held his hand on the walk back, accepted a kiss in public, and let him into her flat for sex, when it could have occurred in any dark back alley. Inside, they sang and clapped to the music, as heard by Eva. They drank four bottles of stout; two of Reid’s and two of Guinness, which were marked with that day’s date and the pub’s address. And then, at the table, they both enjoyed a light meal, with the man opening the salmon tin using a can-opener. As expected, sex followed, as she willingly removed her hat, bra and knickers, but not her dress. She lay on the bed, her back on the sheets, her head on a pillow, and with no signs of a struggle (no cuts, no internal bruising, and no fingernails broken) consensual vaginal sex is believed to be taken place. For at least an hour, this simple sexual transaction between a prostitute and a punter had occurred as it (probably) had two-or-three times prior. For both of them, it was fun, friendly and unthreatening… …only, this time, something would change. With a fist to the face, a lack of struggle suggested that she had been knocked out. With frothy mucus in her airway and bruising about her neck, she was manually strangled at first, but then with a ligature - taken by her killer - it is unknown if it was knotted or if he held it tight until her life had ebbed away. The Police would state “we failed to find anything in the nature of a ligature”. With Marie not wearing any stockings, either he had taken it as a souvenir, kept it as it belonged to him, or it was destroyed in a short ferocious fire which blackened the sink, burnt the curtain and turned the rags within to cinders. With no money in her purse, it’s possible that this ‘trusted punter’ didn’t need to pay her first, or that maybe he only took ‘his money’ back. But with witnesses stating “he had no more than half a crown”; what was his plan? To charm her into charging less, to rob a woman he had begun to like, or – being too broke to pay – did his uncontrollable lust for sex lead this out-of-work man to commit a murder? His motive was a mystery, but – given enough time – his identity would not. Although unknown to any pub locals or West End coppers - with his fingerprints on the can-opener, the bottles, the salmon tin and her handbag – the Police would manually search every fingerprint of every criminal with a history of assaulting women or prostitutes who matched that man’s description, until they found the culprit. It was an almost impossible task… …made simpler having left a few clues. Openly chatting in the pub to two strangers, Frederick Dobson and George Bakewell, Marie’s killer had shared details about his life; his birthplace, his job, his hobbies and his prospects, all except his name. In co-ordination with the Durham Police, they searched for a short, thinly built, mid-twenties man with a round pasty face, who was born or raised in Newcastle. But as he mentioned nowhere specific, their list was too long. The same was said of every coal mine they checked in both Wales and the northeast. A more specific lead was that he was once a boxer: “his last fight was with a man named McGuire who ruined him”. But having interviewed over a thousand boxers, worked with the British Boxing Board, the Amateur Boxing Association and having posted an article in ‘Boxing’ magazine, no-one could recall ‘McGuire’ or his opponent. It’s possible that the witnesses may have misheard, or that the culprit had lied, although some would state that he didn’t look like a boxer, as he looked “sickly” and “weak”. Having said he was unemployed, the Police checked the details of every man who had recently signed on at the Labour Exchange. Having said he was homeless, they searched every lodging house, hotel or casual ward in London and Newcastle, even placing his description in the Police Gazette. And having said he had been sacked, that morning, from the Central Hotel in Marylebone “for upsetting a milk churn”, they questioned the hotel staff, the agency and Ministry of Work, but came up with no-one. The Police placed informants in public areas, witnesses compared photos of possible suspects at the Records Office, and - as they had done with Fifi, Marie and Leah – they requested that every police division in the country compile a list of men with convictions for assaulting women, who matched that description. Every suspect was questioned and investigated, but with solid alibis, all were released. They had evidence, fingerprints, eyewitnesses, and yet, even after weeks of dogged investigation with every avenue of suspicion examined and any possible suspect scrutinised, the case had begun to stall. The Police report states: “the inquiry has been aggravating, for whilst we have witnesses together with the fingerprints to support a conviction, we have no prisoner… we have many witnesses capable of identifying him but up to the moment he is unknown… however no effort is being spared to bring this to a successful termination and… DCI Drewe and his officers are in no way disheartened. I am hoping for a little good fortune to come their way, which has been conspicuously absent so far”. Once again, a strangler had vanished into thin air… …only, he wasn’t a criminal mastermind or a crazed sadistic genius, he was just an ordinary man living in a population of 47 million people, in an era where the best resource the Police had was a card index. For him, it wasn’t difficult to disappear, when the Police don’t know who they’re looking for. His name was Norman Stephenson. Born on the 10th of March 1913, 300 miles north of London in the north-east city of Newcastle, Norman was always an undersized boy, often bullied for being small; and whose weedy frame, ruddy cheeks and pale face - contrasted starkly with his dark brushed-back hair - made him look sickly and weak. He never seemed to let it bother him, but maybe that’s why he lied about being a miner, a boxer and regularly visited prostitutes, as deep down, he was just a little boy who wanted to be seen as a man. Little is known about his upbringing in a small terrace house, just a short walk from Castle Leazes Moor and Fenham Barracks, but often being jolly and chatty to all, he blended in because he didn’t stick out. Educated at St Andrew’s Council School, aged 14, he left being described as “educated, but not smart”, and being too small for heavy labour, his first job in 1927 was as an errand boy for a picture framer. But all that changed when a little mistake left him scarred for life. On 14th September 1927, Norman’s favourite football team, Newcastle FC, were playing against Derby County at St James’ Park. Being too poor to buy a ticket, this little whippersnapper tried to sneak in by shimmying up the six-foot high railings, but slipped. With two iron spikes impaled through his stomach, all he could do was hang there, in pain, as his blood ran from his midriff down to his feet and his face. Hospitalised for three weeks, he would be plagued with bouts of sickness and unemployment for life. After his accident, his work record became sporadic. In 1928, he was a confectioner’s van boy, but quit in 1930 owing to stomach pains. In early 1931, he was off sick, but worked for nine months erecting a concrete garage in Newcastle. And until April 1932, he worked at Park Royal Training in West London, but owing to sickness he returned to Newcastle, where he engaged in casual work and petty crime to fund habitual drinking and sex with prostitutes. Norman Stephenson had ten convictions, mostly for minor offences; on the 27th February 1931 and 8th February 1932 in Gateshead he was charged with ‘acting suspiciously’, 11th January 1933 he did six months in prison for stealing cigarettes, 22nd January 1934 at Newcastle he was fined for stealing two tins of petrol, and on 14th May 1934, he did three months hard labour for stealing women’s clothing. Upon his release, in February 1935, he moved to London, and – as may have been misheard, or a white lie to sound tough - for six months he was a boiler house labourer at the Central Hotel on Marylebone Road. Only he wasn’t sacked for “upsetting a milk churn”, but he left owing to ill-health. And it didn’t happen on 16th August 1937, the morning of the murder, but on 7th June 1935, a year and a half earlier. In the months preceding the strangling of ‘French Marie’, he worked a slew of badly paid jobs in West London, living in lodging houses, crashing on friend’s floors, and committing a spate of minor crimes. On 9th October 1935, at Marylebone Police Court, he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing from a gas metre; on 16th June 1936, back in Newcastle, he served nine months for shop-breaking and (again) for larceny from a gas metre; and on 31st May 1937, in Willesden, West London, he would serve three months hard-labour at Wandsworth Prison for stealing 12s, again from a metre. As a weak and sickly boy, little Norman Stephenson didn’t fit the profile of a murderer; he was a part-time labourer, who suffered with stomach aches, and sometimes stole clothes, stamps and cigarettes. Since the murder of ‘French Fifi’, the Police had sought a man resembling his description, who had a history of violence against women or prostitutes. Only, Norman had no such convictions. In fact, his only violent offence, before he was charged with murder, was the assault of a policeman while drunk. Which begs the question – after almost two years of hunting for this very unlikely suspect - with three murders having gone unsolved and no other suspects for a fourth, as they had done with Stanley King and James Allan Hall, had a baffled Police force simply bagged themselves a convenient scapegoat… ...and was Norman Stephenson an innocent man? Having vanished, it would take seventeen months for the Police to find Norman Stephenson, by which time memories had faded, recollections were hazy, dates had shifted, and faces were lost. His alibi for the day of the murder was not to deny knowing Marie, but to deny that he was even there at all. On Monday 16th August 1937 at 7:45am, Norman Stephenson was released from Wandsworth Prison in South London, having served three months’ hard labour for stealing 12s from a gas metre. Dressed in a shabby brown suit but no hat, with a few coins in his pocket, he boarded the tram to Westminster. From 9am, he said he ate breakfast at the Salvation Army hostel on Great Peter Street, but there is no record of his visit. At 12pm, as Marie entered the Adam & Eve pub, he said he paid a visit to Bertram Bussell’s home near Waterloo Bridge, only his friend wasn’t in. Later, he said he ate lunch at a hostel on Middlesex Street, but again, his details were not recorded there or at any of the nearby hostels. At roughly 1pm, he said he caught a train from Waterloo to Merstham, two hours and 19 miles south of Marie’s flat. At 2:30pm, around the time it is said he entered the pub, his sister said she “gave him five shillings” but “I can’t recall the date”. And with so long having passed - although the Police had his fingerprints on a Guinness bottle as bought by the victim, marked with the pub’s details, dated the day of her death, which was bagged and carried to her flat, and was later found open and drank beside her bed where her body was found - they couldn’t disprove that Norman wasn’t elsewhere… …just as, they couldn’t prove (without a shadow of a doubt) that he had strangled Marie. On 29th October 1937, even with an overwhelming wealth of evidence and only one possible suspect in Marie’s murder - being unaware that Norman Stephenson even existed - the inquest was concluded by the coroner, who would state: “there is no doubt at all that the Police have made all the possible enquiries… it is clearly a case of murder… and there is only one verdict which fits these facts”. Across a few months and several streets in Soho, three women of similar description were strangled by an unseen assailant in almost identical circumstances. And now, declared as ‘murdered by persons unknown’, a fourth woman’s life was lost and her justice denied, as again, her killer would remain free. That night, a foul mood enveloped the detectives, as they knew they had done everything right. When the public pinned the blame on society’s outsiders, and when a feverish press bastardised the facts to concoct silly stories about a monster they had dubbed The Soho Strangler for as long as it sold papers, the Police stayed steadfast in their belief that each victim was murdered by a man with a history of violence against women. But having investigated every possible suspect, they had failed to find him. Only they weren’t wrong. Marie’s murderer had a history of strangling sex-workers… …it was just that, until now, he had never been caught. Sixteen months after the inquest, and 300 miles north in Durham, on the evening of Friday 27th January 1939, 56-year-old Catherine Maud Chamberlain left the home she shared with her husband at Douglas Terrace, passed St James’ Park, and headed to Castle Leazes Moor. It is uncertain why she was there; some say she was “meeting a pal”, whereas others suggest that as the wife of a poorly paid labourer, she was earning a few extra shillings by selling sex to the soldiers stationed at nearby Fenham Barracks. With the snow falling thick and the night bitterly cold, Catherine wore a long woollen scarf to keep the chill from her neck, and a set of rubber wellies, as her feet churned the grass into a brown slushy mud. At 10:10pm. Catherine was seen chatting with a “small man” at the main gates of Leazes Park by Mabel Jackson, they then “made their way together across the park, where there were some ARP trenches”. She described him as “about five foot three, aged about 25, dark hair, ruddy complexion, round face, dressed in a dirty dark suit, with collar and tie, but no hat”. The same as the suspect seen with Marie. Later arrested, Norman would make a confession with chilling similarities. He would state: “I realised there was £2 missing from my waistcoat pocket”; a crime he would blame on Catherine, having been ‘dipped’ in the past, by which a prostitute will either overcharge a punter, or will discretely steal their money - although we have no evidence to prove his assertion of her theft. Feeling aggrieved, “I let her have one blow on the chin”, but only being a little guy, although “she went down against the wall on her knees”, as she started to struggle, he rained down repeated blows to her face as the terrified woman began to scream for her life. It was then that he strangled her to death. Norman would confess, “I grabbed her by the throat”, but being too weak to choke the very life out of her, “I then got hold of her scarf”. Not being the kind of man who plans to murder a prostitute, “as she screamed, I tied a knot in it”, a granny knot, which he knew how to tie in haste being a labourer. And as “I had no intention of killing her”, he’d state, “I did it to frighten her and get my money back”. Which was almost certainly a lie, as in the same way that French Fifi hid her money in her left stocking, Catherine hid hers in her wellies which he removed. This suggests three things; first, that he knew her; second, that he knew she was a casual prostitute; and third, that he knew some of her secrets. At 10:15pm, a passing couple heard several screams by the ARP trench, but by the time they had raced to the Barrack’s wall, finding her body in a pool of mud, Catherine was dead… and her killer had fled. With any evidence eviscerated by the winter sludge, the Durham Police were at a loss as to who this man was. Placing a description of the man in the papers, the press reported the facts in a factual and an unsensational way, but - with only one prostitute dead – this little story would quickly be forgotten. The murder of Catherine Chamberlain may have ended unresolved… …but it was then, that the Met Police got the little bit of luck they needed. As the Met Police had done, Durham Police had requested all divisions across the country to compile a list of men matching that description with a history of assaulting prostitutes, especially strangulation. It was too eerie to be a coincidence, as the man last seen with ‘French Marie’ was from Newcastle. With the press accurately reporting this suspect’s description in the local papers, with his victim’s body found so close to his home and with his face being seen, Norman Stephenson had become spooked. Mid-afternoon on Friday 3rd February 1939, one week after Catherine’s murder, Norman had tried to strangle another prostitute, whilst drunk, on Newgate Street in the heart of Newcastle city centre. In a local pub, having met Annie Cunningham Thomson, a sex-worker who he knew and liked, they headed to an alley for sex, “only nothing happened as he was too drunk”. Moments later, “he put his hands around my neck and tried to strangle me”. Which may have been his real motivation, as with this little boy desperate to be seen as a man, were these assaults because he couldn’t get an erection? Fighting him off, Norman fled as two men came to Annie’s aid. But as he ran into Westmoreland Street, being wracked with anxiety, Catherine’s killer gave himself up. Walking up to PC John Patterson, Norman said “I want to give myself up for murdering Mrs Chamberlain… since the murder, people have said queer things about my appearance”, as reported in the papers “and it has got on my nerves”. Detained at Arthurs Hill police station, he was charged with assault and murder. On Thursday 2nd and Friday 3rd March 1939 at Durham Assizes, Norman Stephenson was tried for the murder of Catherine Maud Chamberlain. Pleading ‘not guilty’, his defence was “I thought she had only fainted”, “I didn’t mean to kill her”, and – claiming self-defence for a knife which was never found - “I thought she had a razor, I was in fear for myself”. But with no prior history of violence, the charge was reduced to manslaughter, as the court knew they hadn’t the evidence to prove any pre-meditation. Having retired for 45 minutes, a jury of eight men and four women found him guilty of manslaughter, and – allegedly flicking a little grin from the dock – he was sentenced to ten years in Parkhurst prison. Throughout the trial, Chief Inspector Drewe absorbed every detail about Norman Stephenson… …but if he was so sure that he had murdered Marie, why did they convict a man called Robert Dixon? With Norman sticking to his shaky alibi and unwilling to admit his guilt, he would state “I know nothing about it. I wasn’t in Euston Road that day. I don’t know the Adam & Eve and I don’t know the woman”. Two years after the murder, he was put on an ID parade at Albany Street police station. Of the thirteen witnesses who had seen him, some of whom had spoken to him - with so much time having passed - only two could positively identify him; Reuben Packcroft and Sadie Gibber, the market stall holders. But backed-up by twenty almost identical eyewitness statements taken on the day after the murder, and with his fingerprints found on the stout bottles, the can opener and the salmon tin found inside her flat and within a very specific timeframe, Norman Stephenson was committed to criminal trial. On 2nd May 1939, ‘Robert Dixon’ was tried at the Old Bailey, as with so much coverage of the murder of Catherine Chamberlain, the prosecution and the defence felt it prudent to try him under an alias. Pleading ‘not guilty’ to murdering Lottie Asterley alias ‘French Marie’, he would state “we were both drunk… she told me to leave and pushed me. I pushed her back and as she fell, I grabbed her silk scarf … and I think it must have tightened”. Only, no-one could recall her wearing a scarf, as it was summer. Having retired for one and a half hours, during which time, the jury had sought rulings from the judge on various points of law, they returned a verdict of ‘not guilty’ of murder, but ‘guilty’ of manslaughter. With Norman Stephenson alias ‘Robert Dixon’ sentenced to 16 years for the manslaughter of Lottie Asterley and 10 years for Catherine Maud Chamberlain, escaping a death sentence, he should have served at least 26 years in prison, but with both convictions to run concurrently, he served just half. Released from Dartmoor prison in 1955, Norman Stephenson died in 1969, a free man. (Fake finish) … ... … (Wind, Ripper sounds as at start of series). 140 years after his killing spree, as it is unknown if Jack the Ripper was ever caught, no-one knows his name, or if he even existed, as with so many theories and conspiracies concocted by a feverish press and a public only interested in what’s sensational, the facts are lost in a quagmire of lies and suspicion. More than 85 years after The Soho Strangler killings, the same could be said, as was he a man, a myth or a monster? There were many suspects over the years, but with very few proven, except maybe one. No-one has ever tried to solve the riddle of who The Soho Strangler was… until now. Since the start, the Police would state “some of the papers have suggested these cases of strangulation of prostitutes in 1935 and 1936 are connected, we have convinced them that they are wrong”. But did they think that, or with only circumstantial evidence of a Soho serial killer, was it quicker and legally safer to conclude one murder as solved, rather than four they could never prove were connected? We know he strangled two women to death, Catherine Maud Chamberlain and Lottie Asterley, as well as assaulting Annie Cunningham Thomson. But with no history of violence against prostitutes, he was never suspected, as his first conviction for strangulation wasn’t until 1939, three years after the murder of ‘French Fifi’. And yet, although we have no sightings of the man who murdered ‘French Fifi’ or Marie Cotton, the suspect last seen with ‘Dutch Leah’ is almost identical to Norman Stephenson: “aged about 25, 5 foot 5 inches, medium build, fresh complexion, brown hair, clean shaven, long black coat and no hat”. It could be a coincidence, or maybe be not. As a small unassuming boy who looked ‘sickly’ and ‘weak’, was he often mistaken for harmless, being so friendly he would chat to strangers in a pub, the kind of punter a prostitute would wave at across a bar, and who she would invite back to her flat for a meal and sex, because she trusted him? He may not have been arrested for violence or sexual assault, but he regularly visited prostitutes, his earliest crimes were for ‘acting suspiciously’ and he was charged twice for ‘stealing women’s clothing’. Was that entirely innocent, or does it hint at something deviant? Prior to their deaths, three of the victims were assaulted by punters, who would claim to have been cheated out of money. Norman would admit “I have been ‘dipped’ before by prostitutes in London”. He also knew Soho and the West End red-light districts, he could tie a variety of knots at speed, and – with no money found at any of the crime-scenes - he knew where Fifi and Catherine hid their earnings. Of course, all of that is circumstantial… but it’s a very different thing to place him at the scene. In neither the press nor the police reports is Norman named as a suspect in any of the ‘Soho Murders’, but by comparing his work history and his prison record, there is a series of startling similarities: Sentenced to two months at Pentonville for stealing from a gas meter, Norman was released on 4th November 1935, the day that Josephine Martin alias ‘French Fifi’ was murdered. Dressed in a shabby brown suit, with no home, no job and no money, it’s likely that prison life had left him sex-starved. On 16th April and 9th May 1936, the days when Marie Cotton and ‘Dutch Leah’ were murdered, being unemployed and kipping of friend’s floors, we know he was in the West End, but for unknown reasons, by his conviction in June 1936 for shop-breaking, he had fled back the Newcastle, where he felt safe. And having been sentenced to three months’ hard labour, released from Wandsworth prison on the morning of 16th August 1937 – with no money, job or lodging – with a need to have sex, he got drunk in a pub, and just hours later, he murdered a prostitute, known as ‘French Marie’, for a few shillings. It could really be as simple as that; there was no myth, no monster nor conspiracy; he wasn’t a crime boss, a sadistic gay or a sinister Jew; as the most obvious answer is usually the right one - that these women were murdered by a recently released convict, who was broke and had a deadly desire for sex. Had the press reported the truth rather than scandal, these women would have received their justice. So, was Norman Stephenson Soho’s serial-strangler… …or was The Soho Strangler just a myth? The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of.

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, all set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE TWO HUNDRED AND FIVE: This is Part Nine of Ten of The Soho Strangler. On Monday 16th August 1937, in the second floor lodging of a 48-year-old casual prostitute known as ‘French Marie’, a fourth French prostitute would strangled to death by an unknown assailant, and in a way which was as identical as the others. But unlike the others, her murderer would murder her was seen, not by one witness, but by at least twenty.

CLICK HERE to download the Murder Mile podcast via iTunes and to receive the latest episodes, click "subscribe". You can listen to it by clicking PLAY on the embedded media player below. THE LOCATION As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location is marked with a purple exclamation mark (!) near the words 'Euston Square'. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

SOURCES: This case was researched using some of the sources below. MEPO 3/1722 - https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1257764 Murder, reduced to manslaughter, of Elsie Charlotte Torchon by Robert Dixon alias Norman Stephenson at Euston Road, NW. on 16 August 1937. STEPHENSON, Norman: at Durham Assizes on 25 February 1939 convicted of manslaughter; sentenced to 10 years' penal servitude; at Central Criminal Court (CCC) on 25 April 1939 convicted of manslaughter; sentenced to 16 years' penal servitude concurrent. PCOM 9/2030 https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1353018

MUSIC: