What happens if you ask Chat GPT or AI software "sarcastically explain who Jack the Ripper was"?25/10/2023 YOU GET THIS....

Oh, certainly! Jack the Ripper was obviously a misunderstood Victorian chef who was simply trying to promote his avant-garde culinary creations. You see, he had a peculiar taste for carving up the finest cuts of meat in the most unconventional and artistic ways possible. His "signature" style of arranging internal organs was just a way to express his passion for gastronomy. In his spare time, he must have moonlighted as a fashion consultant, offering free wardrobe makeovers to those "ladies of the night." His method of disrobing them so meticulously was just a testament to his commitment to the latest fashion trends. Of course, it all makes perfect sense when you look at it this way... or perhaps not. But in all seriousness, Jack the Ripper remains one of the most perplexing unsolved mysteries in criminal history. OR, IF YOU ASK "SARCASTICALLY, EXPLAIN WHO JACK THE RIPPER WASN'T"!? Well, it's safe to say that Jack the Ripper definitely wasn't a time-traveling extraterrestrial ninja with a penchant for parallel universe cuisine. I mean, that would be way too obvious, right? And there's absolutely no evidence to suggest that he was a misunderstood ballet dancer moonlighting as a sous-chef in a Victorian-era fast-food joint. It's also clear that Jack the Ripper couldn't have been a highly trained circus clown who specialized in acrobatic escapology. Such a flamboyant character would surely have left a trail of balloon animals and cream pies at crime scenes, and we have no record of that happening. And let's not forget that Jack the Ripper couldn't possibly have been a disgruntled Victorian-era poet who wrote murderous limericks in his spare time. That's just a bit too poetic for a serial killer, don't you think? LET'S BE HONEST, IT'S A BETTER ANSWER THAT THE CRAP IT USUALLY CHURN OUT :-) OR WIKIPEDIA.

0 Comments

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25.

EPISODE TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY:

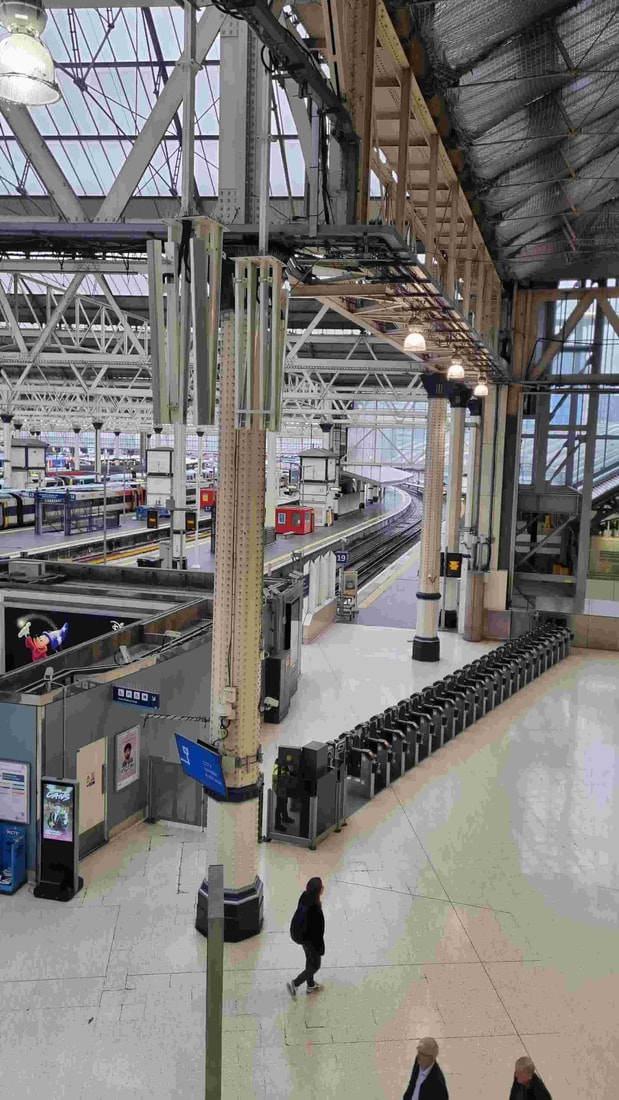

On Monday the 25th of February 1935 at 2:30pm, an unusual parcel arrived at Platform 19 of Waterloo Station. At 21 inches long, 9 inches wide and deep and weighing close to two stone, the train's cleaner found a severed paid of legs. And although to some this was just a piece of lost property, it would lead to one of the strangest criminal investigations in the Met Police’s history.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location is marked with a black coloured exclamation mark (!) near the words 'London Waterlooo'. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other maps, click here.

SOURCES: This case was researched using some of the sources below.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE Welcome to Murder Mile. Today I’m standing in Waterloo Station, SW1; one street south of Peggy Richards’ “fall”, a short walk from the ‘happy slapping’ attack on David Morely, a few feet from the left luggage kiosk where the bloodied bloomers of Emily Beilby Kaye lay, and soon something grim - coming now to Murder Mile. As one of London’s busiest transport hubs, the lost property office at Waterloo Station is a treasure trove of bafflingly bonkers cast-offs which make the cleaners wonder who the hell these weirdos are; having found enough books to fill a branch of Waterstones, walking sticks to stabilise sixty-two wonky centipedes and crinkly-paged grumble mags to milk the saddest git’s love-plums dry. And occasionally, they also find a gimp mask, a llama, a breast implant and (far too often) a stool sample - a human one. But many moons ago, they also found something which sparked a nationwide hunt for a killer. It takes a lot to surprise those who work in this lost property office, and although they still diligently catalogue every object they receive to return each missing item to its rightful owner, what they found back in 1935 would lead to one of the strangest criminal investigations in the Met Police’s history. My name is Michael, I am your tour guide, and this is Murder Mile. Episode 230: Pieces. Usually, at this point in the show, I would introduce you to the victim. With the sad music playing, we would hear about their life, their upbringing, their hopes, their struggles and their dreams, everything from the moment they were born to their last moment alive. But this time, I can’t do that… …I can’t even tell you a few pieces about his life, as that is all that was left of him. Monday 25th February 1935 was bitterly cold, as a Siberian blast had driven London’s winter as low as -28. But in contrast, with highs of 3 degrees and lows of -4, that ice-caked day was practically barmy. The day had begun as it always had, as the train (an electric locomotive with twenty-six carriages) pulled out of a railway siding at Hounslow in West London at exactly 6:48am. Scrubbed and polished by a team of cleaners, the train ran a regular route from Twickenham and Waterloo, stopping at twenty-two stations including Richmond, Mortlake, Barnes, Wandsworth and Clapham Junction. At 1:24pm, the train departed Twickenham Station with hardly a handful of passengers in its first-class coaches, some in the second-class and a smattering in the much cheaper third-class. By all accounts, the journey was uneventful and barring a delay owing to ice, it arrived at Waterloo just shy of 2:30pm. With a light dusting of anonymous passengers disembarking from Platform 19 on the north-west side - all of whom showed their tickets to the inspector – another team of cleaners set about removing any rubbish or lost property from the carriages; maybe some newspapers, some books, and occasionally a pair of missing gloves, a scarf or a woolly hat, although that was unlikely in this bitterly cold weather. A few minutes in, James Albert Eves, one of the cleaners made his way down the third-class carriage numbered 94806, carrying a refuse sack. The train was empty, except for an unidentified man who was dressed in a black suit and hat who – he believed - had boarded for the return leg of the journey. James hadn’t the time to consider the items he’d find and having spotted a brown paper parcel pushed right to the back under the seat - with the biggest crime being to delay the train on its predetermined route back to Twickenham - as it pulled out, James carried the large parcel to the lost property office. Handed to the office supervisor, John George Cooper, both men stared with concern at the parcel. At 21 inches long, 9 inches wide and deep, and weighing close to two stone, wrapped in an odd L-shape, it looked as if it was a fat stubby golf club. Only with its string fraying and the paper wet, James would state “I felt the weight was curious, as at the bottom, when I touched it, it felt like there were toes”. Peeping in through a split, there was no denying what was inside, as John said, “we found legs”. Having alerted the Metropolitan Police, Chief Inspector Donaldson headed up the investigation, aided by Dr Davidson of the Police Laboratory and Sir Bernard Spilsbury as the Home Office pathologist. The brown paper told them nothing, as like the string, it was generic. Unwrapping it, the legs had been swathed in tabloid newspapers; an issue of the Daily Express dated 21st September 1934, six months prior, and two sheets of the News of the World dated 20th January 1935, one month before. But being two of the most popular papers, bloodstains suggested that the dismemberment occurred two days earlier, and with the legs beginning to putrefy, that death had occurred at least eight days before that. Inside were the severed legs of an adult male; complete with shins, calves, ankles and feet, but nothing above the knees. With the lower legs and feet accounting for 12% body mass, weighing roughly 12lbs each, it was clear that he was once a man of 5 foot 8 to 5 foot 10 inches tall, but unable to determine his age – at that point – all they knew was that he was somewhere between 20 to 50 years old. It was impossible to identify him, as he had no scars and no tattoos. Examined at Southwark mortuary, they were able to define his details further, but not much. As being a white pale male, given his fair hair and his freckles, it was assumed that he worked outdoors, and having the musculature of a ‘healthy vigorous male’, x-rays showed no signs of ‘Harris Lines’ (the arrest of bone growth in his teens) or any ‘senile changes’, so it was likely he was in near to his late twenties. But as hard as they tried, the victim couldn’t be identified by his lower legs, and that’s all they had. The wounds told them even less about who had dissected them and why, as with “a clean cut through the soft tissue of the knee joint, just below the patella… it was carried out with extraordinary precision by a person with anatomical knowledge”. But who? A surgeon? A butcher? Or was it just blind luck? And yet, one detail would perplex these officers more than most. With the victim’s toes bent like clenched fists as if to make them smaller, given that his legs were shaved, it suggested that either this man had been so poor that he was forced to wear ill-fitting shoes as hand-me-downs, or he’d been masquerading as a woman. Whoever this man once was, the Police had little to go on… …but they were unwilling to give up. Every passenger who could be traced from the train was questioned, but no-one saw anyone carrying a large parcel or anything strange. But then, how often do we notice other people? And with the parcel deliberately pushed back under the seat, it was hidden, but why would anyone hide a pair of dismembered legs onboard of a train which was heading back to its original location? Had the early morning cleaners at the railway siding missed it by mistake, or had someone planned to dump them? Examining the generic brown paper using infra-red light and microscopic analysis, Dr Olaf Block of the Ilford Photographic Company was able to spot two very faint numbers; a partially erased ‘5’ written in black crayon on the bottom left-hand corner, and a ‘14’ written in pencil in the right-hand corner. Across the city and wider boroughs, Police questioned every courier, freight and removals firms, as they were most likely to mark a parcel with identifying numbers, but it came to nothing. And although this tatty brown paper had been used several times previously, not a single fingerprint was found. The newspapers were submitted to the same scrutiny, as with top-right-hand portion of the front page of the Daily Express having been cut away with a sharp knife or a razor, given that this is where some newsagents tend to write the address of the house where the paperboy should deliver it, the Police spoke to hundreds of vendors, but that cut wasn’t unique enough and the handwriting didn’t match. And although they had enlisted the help of two sculptors from the infamous Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum on Baker Street who made plaster casts of these unusual feet, no-one could identify them. Every piece of evidence had only led to dead ends, and every theory had hit a brick wall. It was suggested that – given how cleanly the legs were dissected – it could have been a prank by a medical student who had removed a pair of amputated limbs from a hospital incinerator. But with the feet being unwashed and the wound devoid of a surgical skin-flap, this theory was quickly discounted. Enquiries were made at hospitals, undertakers and mortuaries whether any body parts were missing, but this turned up nothing. As did the hunt for a butcher or abattoir worker who could have performed such a skilled dissection, “as the knees are particularly hard to disarticulate”, but this too drew a blank. And with the Police appealing for any relatives who were missing a loved one to get in touch, a deluge of families gripped with grief from across the country – regardless of whether their husband, brother or son was a 5 foot 9, fair-haired male in his late 20s, or not – they swamped the phonelines for weeks. So desperate were the Police to solve this case that they had begun to find similarities in the Brighton trunk murders from the year before. But later being dismissed as a theory by Sir Bernard Spilsbury, they were left wondering - why would anyone go to so much effort to disguise the victim’s identity? Or had they? Whether it was a murder or not, they still did not know. Whether he was still alive, they couldn’t tell. And although the Police had some evidence of who this man may have been… …that was all they had – pieces. Three weeks later, on Tuesday 19th March 1935 at about 5:30pm, three boys were playing on the bank of the Hanwell Flight of the Grand Union Canal. As a series of seven locks from the Hanwell Asylum to the River Thames at Brentford, passed a chocking swathe of factories and under two bridges for the Piccadilly Line tube and Southern Railways, Clitheroe Lock was the last before the Great West Road. Having had his tea, 14-year-old Ronald Newman was watching a 70-foot-long cast-iron barge exit the lock, as its weight displaced tonnes of water below it as it slowly headed downstream. But as the wake disturbed the dark calm of the water, “I saw something bobbing up and down”, a little patch of brown as a sack floated on the surface, as underneath a meniscus of mildew, the bulk of its contents dipped. Grabbing a stick, as Ronald drew it near, it was clear that this wasn’t a bag of rubbish, as the sack was as big as a medium sized dog, diamond shaped like a giant stinkbug, and weighed several kilos at least. Heaving with all their might, as the lads wrenched the drenched sack onto the bank, hearing a tearing, they quickly wrestled it ashore as the old rotten sack split. But as Ronald grabbed at its sodden base, as his hand slipped inside the sack, it also slid into a wet festering ooze which stunk like rotting meat. Withdrawing his hand, inside he saw a gaping wound of flesh, and as it slowly dried, within seconds a fever of hungry flies had begun to swarm and feast, at what Ronald knew was “a man’s severed neck”. Having alerted a local Bobby, within the hour, the Met’ Police were on the scene. Untying the string which sealed this hessian sack shut, inside lay a man’s torso; no forearms, no waist, no legs and no head, just a torso. Wearing a tatty brown woollen vest, he hadn’t any of the ordinary clothes a man in his era would wear, no jacket, no shirt nor a tie, just a vest. And with all but the top two buttons missing, and a portion of the lower-left corner having been cut away, it was likely that someone had tried to disguise his identity by removing the laundry marks - but this was just a theory. Having been submerged in the feted water of the canal for several weeks, owing to the decomposition, it was impossible to accurately determine when he had died, or even when he had been disposed of. With his breastbone, every rib and several vertebrae either broken or fractured, with a few ribs poking through the skin like white jagged spears, although the chest had been completely crushed, this wasn’t how he had died as these injuries had all occurred post-mortem, as the cast-iron barges rolled over it. Only this wasn’t an accident, or a body part missing from a morgue, this was undeniably a murder. With no hands nor head found, the erasing of his identity was paramount for the killers, but with the dissection lacking a surgeon or a butcher’s skill, this dismemberment was described as “rather crude”. Lacking the clean slices of a sharpened blade, it was as if someone had been in haste to dispose of this body as quickly as possible, or maybe several men of differing skills had taken it in turns at a side each? Severed at the elbow, the left arm was cleanly cut through the humerus, the radius and the ulna, and where-as the right had been hacked, as a rough jagged knife had ripped the skin and tore at the flesh. With the stomach as crudely ripped as if someone had split a bag of rice, spilling the intestines and its red lumpy guts like a slops bucket at an abattoir, across the top of the hips lay a band of rough tears where the blade had caught and tugged, as a skin flap hung over the innards like a damp cloth cap. And with the neck little more than a fleshy stump severed by blows with a blade and a swung axe, this wasn’t the work of a professional anatomist but a crude killer with a body to disguise. And yet, spotting two wounds to his heart which exactly matched two cuts in the vest, there was no denying… …he had been stabbed to death. The torso told the Police these few facts; as a white male with fair hair, pale skin, freckles and his age initially suspected to be in his 40s to 50s but later determined by x-rays to be in his late 20s, as a well-built broad-shouldered male of roughly 5 foot 9 inches in height, it was likely he was a manual worker. Removed to Brentford mortuary in the grounds of a local gas works, Sir Bernard Spilsbury determined several key details; one, this man was healthy when he died; two, his death was unnatural; and three, there was “a strong presumption” that this torso belonged to the two legs found at Waterloo Station. So, although submersion in water for several weeks had rendered a time of death impossible, based on the legs, it was likely he had been murdered near the 15th February and was dismembered on 23rd. And yet, another unusual detail would pepper this case, as along with his shaved legs and small feet which suggested he was “masquerading as a woman” (a theory which could never be proven), three four-inch-long dark hairs – possibly made from a woman’s real-hair wig – were found on his body. But were they a message, or a mistake? With this stretch of the canal being remote, although questioned, there were no witnesses who had seen anything suspicious, or heard a sack being dumped in the water. But how did he end up here? The Thames Police were requisitioned to drag and drain three miles of the canal, with several hundred yards of it dredged and manually searched, but nothing of significance was found. All barge crews travelling from Coventry to London were interviewed, as well as nomads on the banks, and officials of the Grand Union Canal supplied details about the sluice gates and water flow, but it proved fruitless. One theory as to why the torso was found here was owing to its location, as 200 yards above the lock sits Bridge 206A, which runs the Piccadilly Line train between Boston Manor and Osterley, and 300 yards below sits Bridge 207A, which runs Southern Railway trains from Hounslow to Waterloo Station. The Police mulled over the thought that the torso had been thrown from the train into the canal, and that – maybe - with the severed head and arms tossed into one of several miles of woods or ditches along the train track, and that – maybe - with too many passengers onboard, the killer hadn’t the time to dump the legs before the train reached its destination at Waterloo Station – this was considered. But although the Twickenham to Waterloo train doesn’t pass through Hounslow, and Bridge 207A was downstream from where the body was found, having checked every track siding, nothing was found. That said, the killers could have changed trains, or maybe it was just a coincidence? But with so much evidence leading to this neck of the woods, the Police truly believed that the murderers were local. But who were they, and where were they? With very little to go on, the Police set about tracing the brown woollen vest, hoping that its purchase would lead to the purchaser. Made by Harriot & Coy at a cost of 2 shillings and 6 pence, although this mass-produced vest was distributed to thousands of wholesalers each year, the label was used by one company – a Midlands based garment maker who also sold it to the North of England and Scotland. Every shop which sold the ‘Protector’ brand was questioned, from Bishopsgate to Argyl, Cheapside to Glasgow, but with few records kept of who had purchased this vest, this line of inquiry would stall. As for the sack, with it bearing the name ‘Ogilvie’, a flour manufacturer of Montreal in Canada, when examined, the company confirmed the sack was made in 1929, but was one of 1000s sent to the UK. And although missing persons reports were read for every British county against anyone who matched that description, every lead was checked and proved to be a dead end, and with a less-than-respectable tabloid reporting the discovery of a severed head in Ealing, that was proven to be a lie. With no fingerprints, no teeth, no ID, no laundry marks and no face, his identity was a mystery. Two of the most promising leads they had came in the weeks before the inquest. Continuing the use infra-red rays on the brown paper, Dr Olaf Block had found four words which had been erased – they were “Harry”, “Hanwell” and “Ward 14”. Interviewing the postal clerk at Hanwell Mental Hospital at the back of the Hanwell Flight of the Grand Union Canal, he confirmed the writing was his… but unable to trace who “Harry” was amongst those in “Ward 14”, that clue led to nothing. And the final lead occurred on Monday 25th February at 1pm, 90 minutes before the severed legs were found. At Hounslow Station, Harold Hillier, an attendant saw three men in the booking hall, at their feet lay a large brown-paper parcel. Only one of the men boarded the 1:06pm train to Waterloo, and although he was described as late 20s, medium build and fair-haired, we know he wasn’t the victim. Departing on time, this train didn’t originate in Twickenham, but it did cross the Grand Union Canal at Bridge 207A, downstream of the Clitheroe Lock, where the torso was found. And although the legs were found on a different train, he could have changed at Clapham Junction, or unable to throw them out the window, having arrived at Waterloo Station, maybe he hid them on an outward-bound train? Who these men were nobody knew, but with Harold’s statement backed-up by his colleague Thomas Shea, they confirmed this - that all three men were either Welsh or Irish miners, many of whom were employed locally by McAlpine, who were working on the sewage works and road construction. (End) That clue took the Police one step closer to the victim’s identity. Having questioned Alfred McAlpine, owner of McAlpine Construction, they went through the payroll and employment records for their workers over the last year. But with no-one known to be missing and many of them paid in cash, officers would state “this appeared a most likely clue, but it revealed little hope of success as the firm’s labourers are the flotsam and jetsam of Ireland and Wales”. They had so many clues, but equally as many dead ends and loose threads. On the 10th of April 1935, an inquest was opened at Southwark Mortuary. But with no suspects, no witnesses, no weapon, no fingerprints, and no crime scene to the murder or the dismemberment, on the 6th of June, an ‘open verdict’ would remain into an unknown male torso and a pair of severed legs. Chief Inspector Donaldson would state “every possible enquiry has been made to establish the identity of the victim, but without success. Vigorous but negative efforts have also been made to obtain the identity of the person or persons responsible for this offence”. And with that, the case was closed. Who the victim was will never be known, nor will the resting place of his forearms and head. We don’t know his name, his home or the location of family. We don’t know what he had done, why he was killed, or who by? And denied a proper burial, all that we know of him is all he will ever be… pieces. The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. The abolition of the death penalty in Britain marked a significant milestone in the history of criminal justice and human rights. This transformation, spanning over several decades, showcases a remarkable shift in societal values and the recognition of the fundamental importance of human dignity. In this article, we will explore the journey of how and why Britain abolished the death penalty.

For centuries, the death penalty was a ubiquitous part of the British legal system, with a wide range of crimes carrying the ultimate punishment, from murder to seemingly minor offenses like theft or forgery. Public executions were a gruesome spectacle, attended by large crowds. However, the 20th century saw a shift in attitudes towards capital punishment. The Role of World Wars. The devastation of the two World Wars played a crucial role in reevaluating the death penalty. The loss of millions of lives during these conflicts prompted a more critical reflection on the value of human life. The concept of retribution, central to the justification of the death penalty, came under scrutiny as societies grappled with the overwhelming human cost of war. The Homicide Act of 1957. One of the most significant legislative steps toward abolition was the Homicide Act of 1957. This act established the "partial defence" of diminished responsibility, which allowed courts to consider the defendant's mental state when determining the sentence. It was a recognition that not all murderers were equally culpable, and some may have been driven to their crimes due to factors beyond their control. The Abolition of the Death Penalty for Murder. The first practical step towards the abolition of the death penalty came in 1965, when the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act was passed. This act abolished the death penalty for murder in Great Britain and replaced it with a mandatory life sentence. While capital punishment for murder was retained in Northern Ireland, this marked a significant turning point in the broader movement against the death penalty. The United Nations and International Pressure. International pressure also played a role in Britain's decision to abolish the death penalty. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, emphasized the right to life and the incompatibility of the death penalty with human rights principles. This global shift towards human rights was reflected in British policies. Public Opinion and the Decline of Executions. As the 20th century progressed, public opinion began to turn against the death penalty. High-profile miscarriages of justice, like the case of Timothy Evans, who was wrongfully hanged for a murder he did not commit, stirred public outrage. Advocacy groups, such as Amnesty International, campaigned vigorously against capital punishment. The Death Penalty Abolished in Northern Ireland. In 1973, capital punishment was finally abolished in Northern Ireland, marking the end of executions throughout the United Kingdom. The decision was largely influenced by the same factors that led to the abolition in Great Britain, including shifting public opinion and international human rights considerations. The abolition of the death penalty in Britain reflects a broader global trend towards the recognition of the fundamental right to life and the rejection of the death penalty as a form of punishment. The role of international pressure, evolving societal values, and legislative changes like the Homicide Act of 1957 all played a crucial role in this significant transformation. The United Kingdom's decision to abolish the death penalty was a testament to the evolving understanding of justice and human rights, as well as a commitment to upholding the inherent dignity of all individuals. Serial killers and murderers often display cunning and meticulous planning to evade capture, making them some of the most elusive criminals. However, history is replete with instances where these ruthless criminals made grievous mistakes, leading to their eventual capture. This blog explores some of the most astonishing cases of murderers who got caught due to bizarre blunders, reminding us that even the most cunning criminals can falter. The BTK Killer's Careless Taunting. Dennis Rader, known as the BTK Killer (Bind, Torture, Kill), terrorized Kansas from the 1970s to the 1990s. Despite his apparent intelligence, he made the crucial mistake of sending letters to local newspapers and the police, taunting them about his crimes. In one letter, he included a floppy disk containing metadata that could be traced back to a computer at his church. This slip-up led to his capture in 2005, ending his reign of terror. Ted Bundy's Reckless Traffic Stop. One of the most infamous serial killers, Ted Bundy, had a knack for escaping custody multiple times. However, his eventual capture was a result of a routine traffic stop in Utah. Bundy's Volkswagen Beetle was pulled over by the police, and upon searching his car, they found burglary tools and suspicious items. This arrest ultimately led to the discovery of his horrific crimes. 3. Richard Ramirez's Fingerprint Blunder The Night Stalker, Richard Ramirez, terrorized Southern California in the mid-1980s. He committed a series of gruesome murders and assaults. Ramirez's capture came about when he carelessly left behind a fingerprint on a mesh screen during one of his break-ins. When this print was matched to him, it led to his arrest, trial, and eventual conviction. 4. Gary Ridgway's DNA Oversight Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer, targeted vulnerable women in the Pacific Northwest during the 1980s and 1990s. He managed to evade capture for many years, but his undoing came when DNA evidence was used to link him to the crime scenes. Years later, he was arrested and eventually confessed to murdering 71 women. 5. The Pizza Delivery That Unraveled Mark Goudeau Mark Goudeau, a serial rapist and murderer known as the "Baseline Killer" in Arizona, was captured in 2006 when he made the mistake of ordering a pizza for delivery from a crime scene. When the delivery driver arrived, they noticed the suspicious circumstances and called the police, leading to Goudeau's arrest. 6. The Facebook Post That Snared Antwone Fisher In a bizarre and almost unbelievable twist, Antwone Fisher, a convicted murderer, was captured in 2011 due to a Facebook post. Fisher had been on the run for several years when he posted a status update on his Facebook page, revealing his location. An astute tipster saw the post, contacted the authorities, and Fisher was apprehended. 7. A Zodiac Cipher Unraveled The Zodiac Killer is one of the most enigmatic and mysterious criminals in history. Despite taunting police and the media with cryptic ciphers in the late 1960s, he was never identified or caught at the time. However, in 2020, a team of amateur codebreakers finally cracked one of the Zodiac's unsolved ciphers. The deciphered message revealed the name of a deceased acquaintance of the killer, leading to speculation about his identity. While the Zodiac Killer remains unidentified officially, this codebreaking breakthrough brought the case back into the public eye. 8. Joseph DeAngelo's DNA Slip-Up Joseph DeAngelo, also known as the Golden State Killer, terrorized California in the 1970s and 1980s. He committed a string of burglaries, sexual assaults, and murders without being caught. But his downfall came in 2018, thanks to a combination of advancements in DNA technology and his own carelessness. Investigators used genealogical databases to trace his DNA back to distant relatives, eventually leading them to DeAngelo. They then collected his discarded DNA from a public place, confirming the match and ultimately arresting him. His decades-long reign of terror ended due to advances in forensic science and a misjudgment of his own genetic trail. 9. The Craigslist Killer's Digital Footprint Philip Markoff, dubbed the Craigslist Killer, lured victims through online classified ads and subsequently killed them in a series of brutal attacks. However, his foolish mistake was leaving a digital trail. He used his personal email and phone number when communicating with his victims, allowing investigators to trace him back to his online activities. The electronic evidence became a crucial factor in his arrest and conviction. 10. The Green River Killer's Intentional Oversight Gary Ridgway, known as the Green River Killer, committed a staggering number of murders, possibly exceeding 70 victims. His cunning tactic was to dump his victims' bodies in remote areas, making it difficult for law enforcement to connect the crimes. However, his audacious error was a result of the meticulous record-keeping he maintained regarding his murders. He maintained a list of victims and their locations, which eventually fell into the hands of investigators, leading to his arrest and life imprisonment. 11. Richard Ramirez's Failed Carjacking Richard Ramirez, the infamous "Night Stalker," terrorized Los Angeles in the 1980s. His reign of terror came to an end when he attempted to carjack a woman in 1985. The intended victim fought back, and Ramirez fled the scene on foot. The woman noted his description and his abandoned car, which contained critical evidence. This mistake, combined with the subsequent identification, led to his arrest and eventual conviction. 12. The Slip-Up in Ted Bundy's Beetle Ted Bundy, one of the most notorious serial killers in American history, had an intelligent and charming façade that allowed him to evade capture for years. However, in 1975, he was pulled over by police in Utah for a suspicious vehicle. Inside his Volkswagen Beetle, officers found burglary tools and ski masks. Bundy was arrested and later connected to a string of murders and abductions, ultimately leading to his execution. 13. Pedro Lopez - The Monster of the Andes Pedro Lopez, known as "The Monster of the Andes," was responsible for the murders of hundreds of young girls in South America. His reign of terror ended when he attempted to abduct a young girl in Ecuador, but her cries for help drew the attention of local villagers who captured and beat him. The police later took custody of Lopez, leading to his capture and eventual conviction. 14. The Shoe Fetish of Jerry Brudos Jerry Brudos, also known as the "Lust Killer" and the "Shoe Fetish Slayer," was a serial murderer who preyed on young women in Oregon in the late 1960s. Brudos had a bizarre fetish for women's shoes and was known to keep souvenirs from his victims. This obsession ultimately became his undoing when he was apprehended trying to steal shoes from a department store. Suspicious employees called the police, who discovered evidence linking him to the murders, leading to his arrest. 15. The Facebook Posts of Christopher Cullen In 2009, Christopher Cullen, a nurse at a New Jersey hospital, was convicted of killing 22 patients by injecting them with lethal doses of medications. He might have continued his murderous spree if it weren't for his own Facebook posts. Cullen had made numerous alarming and incriminating statements online, which led to an investigation into his activities. These posts provided crucial evidence linking him to the murders and ultimately led to his conviction. 16. Aileen Wuornos - The Prints on the Stolen Car Aileen Wuornos was one of America's most infamous female serial killers. Her killing spree came to an end when she was arrested in 1991 for an outstanding warrant, stemming from a routine check on a stolen car that she was driving. Subsequent investigations connected her to a string of murders, resulting in her conviction and execution. Of course, the United Kingdom has had its fair share of notorious serial killers and murderers who have struck terror into the hearts of the public. While many of these criminals eluded capture for extended periods, some were eventually brought to justice due to the most unexpected and seemingly trivial mistakes. In this blog, we'll explore the dark and chilling stories of British serial killers whose reigns of terror came to an end because of their own foolish errors. 17. Dennis Nilsen - The Strangely-Spacious Flat Dennis Nilsen, one of Britain's most infamous serial killers, was responsible for the murders of at least 12 young men in London during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Nilsen's spree of heinous crimes came to an end when a plumbing mishap in his apartment building led to the discovery of human remains clogging the drains. This blunder led to Nilsen's arrest, as it was determined that he had been dismembering his victims and flushing their remains down the toilet. 18. Harold Shipman - A Baffling Signature Harold Shipman, a trusted family doctor, carried out a horrific killing spree that spanned over two decades. He is believed to have murdered around 250 of his patients, administering lethal doses of prescription medication. It was not until a fellow doctor noticed an unusual pattern in the number of deaths under Shipman's care that suspicion was raised. His mistake? Shipman had forged the will of one of his victims, leaving her entire estate to himself. This blatant act of greed ultimately exposed his sinister deeds, leading to his arrest in 1998. 19. Peter Sutcliffe - A False Number Plate Peter Sutcliffe, infamously known as the "Yorkshire Ripper," terrorized the north of England in the late 1970s. He was responsible for the brutal murders of 13 women and the assault of several others. Sutcliffe's reign of terror was brought to an end in January 1981 when he was caught with false number plates on his car. Suspicion was raised, and a subsequent search of his vehicle revealed a hammer and knife, which linked him to the murders. This seemingly insignificant traffic offense led to his arrest, and he was subsequently convicted of multiple murders. 20. Levi Bellfield - A Simple Parking Ticket Levi Bellfield, a serial killer and rapist, operated in London during the early 2000s. His crimes involved the murder of several young women and girls. Bellfield's eventual downfall can be traced back to a relatively minor parking ticket. In 2004, he received a parking ticket near the scene of one of his crimes. This seemingly inconsequential detail later contributed to his arrest when detectives connected him to the location and his victims' disappearances. 21. Colin Ireland - The Bragging Letter Colin Ireland, also known as the "Gay Slayer," targeted gay men in London during the mid-1990s, committing a series of gruesome murders. In an astonishing act of arrogance, Ireland sent a handwritten letter to a local newspaper in which he claimed responsibility for the murders, signing it with his real name. Detectives quickly traced the letter back to him, leading to his capture and subsequent confession. 22. John Christie – The Rillington Place Strangler John Christie was a British serial killer responsible for the murders of at least eight people, including his wife, Ethel, and several women he lured to his residence at 10 Rillington Place, London. Christie's critical mistake came to light when the new tenant at Rillington Place discovered the concealed bodies of his victims in the garden and under the floorboards. Christie's heinous crimes were exposed, leading to his arrest and execution. 23. The Suffolk Strangler – Steve Wright Steve Wright, also known as the Suffolk Strangler, committed a series of murders in Ipswich, Suffolk, in 2006. The critical error that led to his capture was captured by surveillance cameras. Wright was recorded picking up his victims in his car, which later linked him to the crimes. His arrest and subsequent confession put an end to his killing spree. 24. Stephen Griffiths, the Crossbow Cannibal Stephen Griffiths, dubbed the "Crossbow Cannibal," was responsible for a series of gruesome murders in Bradford, England. He believed he could outsmart the police, but his desire for notoriety led to his downfall. Griffiths approached a police officer while wearing a bowler hat and told them, "I'm the Crossbow Cannibal." His bragging ultimately led to his arrest in 2010, and he was convicted of the murders. 25. Colin Pitchfork Colin Pitchfork is known as the first person in the world to be caught using DNA evidence. His murder of two teenage girls in the 1980s rocked the UK. However, it was not his careful planning that led to his arrest, but rather his arrogance. Pitchfork convinced a friend to take a DNA test in his place, but the friend's suspicious behavior raised alarms. When police investigated further, they found inconsistencies in Pitchfork's story, leading to his arrest. 26. The Moors Murderers - Ian Brady and Myra Hindley While Ian Brady and Myra Hindley were not caught due to a single mistake, their ultimate capture can be attributed to their ill-conceived recording of the abduction and murder of 10-year-old Lesley Ann Downey. The tape contained incriminating evidence, and the police, upon discovering it, were able to link the couple to the heinous crimes they had committed on Saddleworth Moor. 27. Ian Huntley - The Soham Murders One of the most shocking cases in recent British history was the murder of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in Soham, Cambridgeshire, in 2002. Ian Huntley, the school caretaker and perpetrator of the crime, made a series of errors that led to his capture. Notably, he lied about his involvement, and his account of events was inconsistent with the evidence. This inconsistency, along with other suspicious behaviors, eventually led to his arrest and conviction. 28. John Straffen John Straffen was a notorious British child killer who committed several murders in the 1950s. He was initially apprehended, but during his time at a psychiatric hospital, he managed to escape in 1952. However, his escape was short-lived as he made the mistake of asking a police officer for directions, not realizing that he was conversing with the very people he was trying to avoid. This error led to his recapture, and he remained in custody until his death. 29. Peter Manuel Peter Manuel was a Scottish serial killer who murdered multiple people during the 1950s. His capture was largely due to his arrogance and lack of caution. He sent taunting letters to the police, signed his real name, and even included a confession to one of the murders. This gave the police the break they needed to apprehend him, and he was later executed for his crimes. 30. John George Haigh John George Haigh, the notorious "Acid Bath Murderer," killed at least six people during the 1940s. His unique method of disposing of the bodies by dissolving them in sulfuric acid initially allowed him to escape detection. However, his ultimate mistake was attempting to cash in on his victims' assets. After forging their signatures and selling their belongings, he attracted the attention of authorities and was arrested. Haigh's confessions to the murders during his trial sealed his fate. While many serial killers and murderers seem to possess an uncanny ability to evade the law, their reigns of terror often come to an end due to unforeseen, sometimes trivial mistakes. The cases mentioned here are a stark reminder that even the most calculated criminals can falter, and justice can prevail. These blunders demonstrate the crucial role that diligence, technology, and the watchful eyes of the public play in bringing perpetrators to justice, ultimately making the world a safer place. True crime has been a source of fascination for many people for decades. Whether it's through books, documentaries, podcasts, or TV shows, we are drawn to the mysteries and intrigue surrounding real-life criminal cases. However, there's a growing concern that our society's infatuation with true crime might be more harmful than we realize. In this blog, we'll explore why we shouldn't glamorize true crime and the potential consequences of doing so.

1. Human Tragedy and Sensationalism One of the most significant reasons to reconsider our fascination with true crime is the inherent exploitation of human tragedy. These stories often involve heinous crimes, violent acts, and profound suffering. By glorifying or sensationalizing these events, we risk disrespecting the victims and their families, who have already endured immense pain and loss. 2. Desensitization to Violence Exposure to graphic and disturbing content through true crime media can lead to desensitization to violence. When we consume such content regularly, it can become challenging to empathize with the real-life pain and suffering of those affected by crime. This desensitization may contribute to a broader societal issue of diminishing empathy and compassion. 3. Perpetuating Stereotypes True crime narratives often rely on stereotypes to tell their stories. This can perpetuate harmful biases and preconceived notions about certain groups of people. It's essential to recognize that the criminal justice system can be flawed, and by consuming true crime content without critical thinking, we may inadvertently support these harmful stereotypes. 4. Distraction from Important Issues Our fascination with true crime can sometimes serve as a distraction from more pressing social issues. Instead of focusing on systemic problems like poverty, inequality, or healthcare, we find ourselves engrossed in the minutiae of individual criminal cases. While true crime is undeniably interesting, we must strike a balance between consuming this content and addressing larger societal challenges. 5. Ethical Dilemmas in Entertainment The true crime genre often presents ethical dilemmas within the realm of entertainment. Exploiting real-life tragedy for the sake of entertainment raises questions about the boundaries of our moral responsibility as consumers of media. Where should we draw the line between entertainment and respect for the people involved in these stories? 6. Disturbing the Grieving Process For families and individuals affected by the crimes featured in true crime stories, the constant reminder of their trauma can be distressing. The rehashing of their experiences in the media can inhibit the healing process, as well as make it difficult for them to move forward and find closure. While it's natural to be curious about the mysteries and dark sides of human nature, we should be mindful of the potential consequences of glamorizing true crime. It's essential to engage with this content responsibly and critically, taking into account the real-life pain and suffering involved. Rather than glorifying these stories, we should strive to support and advocate for a more empathetic and compassionate society. By doing so, we can strike a balance between our natural fascination with crime and a more responsible, ethical approach to consuming true crime media. True crime has become a global cultural phenomenon. It dominates our television screens, bookshelves, and podcasts, and countless online communities revolve around the discussion of real-life criminal cases. But what is it about tales of murder, mystery, and malevolence that keeps us so captivated? In this blog, we'll delve into the psychology and societal factors behind our obsession with true crime.

1. Human Nature and Curiosity. At its core, our fascination with true crime may be an extension of our innate curiosity. Humans are naturally drawn to puzzles and mysteries. We have an insatiable desire to understand the world around us, and true crime presents an opportunity to satisfy this curiosity. We want to know the "why" and "how" behind the crimes, and we're often left intrigued by the complexity of human behavior. 2. Voyeuristic Thrills True crime offers us a voyeuristic thrill—a chance to peer into the darkest corners of the human psyche. This experience can be both chilling and cathartic. It allows us to confront our fears from the safety of our own living rooms, experiencing the horrors without actually being in danger. 3. Empathy and Relatability Many people find themselves empathizing with the victims and their families in true crime stories. The shared experience of fear, grief, and trauma can make these stories feel relatable. This emotional connection helps us explore our own fears and vulnerabilities, making us feel more human in the process. 4. Morbid Fascination There's no denying that we're drawn to the macabre and the mysterious. The shock value of true crime stories can be both titillating and disturbing. Morbid curiosity, as some psychologists call it, leads us to explore the darker aspects of human existence, even if it's unsettling. 5. The Puzzle of Justice In many true crime stories, there is a pursuit of justice. We become armchair detectives, trying to solve the case alongside law enforcement. The search for the truth and the quest for justice can be deeply satisfying, reinforcing our belief in the triumph of good over evil. 6. Fear and Self-Preservation True crime can also serve as a form of self-preservation. By learning about real-life crimes, we become more aware of potential dangers and how to protect ourselves and our loved ones. Knowledge about past crimes can help us make safer choices in our own lives. 7. Social Connection The popularity of true crime has led to the formation of vast online communities, book clubs, and discussion groups. Engaging in these communities allows people to connect with others who share their interests, creating a sense of belonging and camaraderie. 8. Psychological Thrills The psychology behind criminal behavior is a fascinating field of study. True crime offers a unique window into the minds of criminals and the intricate motivations behind their actions. This intellectual aspect can be highly engaging for those who seek to understand the intricacies of human behavior. Our obsession with true crime is a complex interplay of human psychology, curiosity, and societal factors. While it might seem morbid to some, there's much more to it than a mere fascination with violence and mayhem. True crime stories provide us with an opportunity to explore the depths of the human psyche, to grapple with our own vulnerabilities, and to find solace in the pursuit of justice. Ultimately, the popularity of true crime is a testament to our enduring need to understand and connect with the darker aspects of the human experience. The world of serial killers and murderers has long captivated the public's imagination. The depraved acts of individuals who commit such heinous crimes are often incomprehensible to most of us. Yet, one aspect of their lives that has received relatively less attention is their early years, specifically the nicknames they earned during childhood and how those nicknames may have played a role in shaping their twisted paths. In this blog, we will delve into the disturbing connections between cruel childhood nicknames and the psyches of some infamous serial killers. Childhood is a time of innocence, curiosity, and vulnerability. The nicknames children earn during these formative years can significantly affect their self-esteem, emotional development, and, in some cases, their future behavior. When cruel or derogatory nicknames are inflicted upon a child, the consequences can be deeply damaging. Serial killers and murderers are no exception to this pattern. Children often resort to name-calling and teasing as part of the socialization process. These behaviors may be seen as harmless in most cases, but they can take a dark turn in certain circumstances. Some kids, for various reasons, become the targets of relentless taunting, leading to the development of particularly cruel nicknames.

The cruel nicknames assigned to these individuals during their formative years may have contributed to their descent into psychopathy. The emotional scars inflicted by these labels can manifest in various ways, such as feelings of inadequacy, isolation, and the need to prove themselves. Some killers may have sought infamy and recognition as a way to compensate for their perceived deficiencies, while others may have developed warped views of normalcy. Furthermore, these childhood nicknames may have played a role in eroding the killers' empathy and conscience, making it easier for them to commit acts of extreme violence and cruelty. While it is essential to understand that not every child who endures a cruel nickname during their formative years becomes a serial killer, there is a connection between early emotional trauma and the development of psychopathic traits in some individuals. The stories of serial killers like Ed Gein, Richard Ramirez, and Jeffrey Dahmer serve as chilling reminders of how factors such as cruel nicknames can contribute to the creation of monsters.

The complex interplay of genetics, upbringing, and personal experiences shapes the minds of these individuals. Examining the role of childhood nicknames is just one piece of the puzzle. Ultimately, addressing the issue of childhood trauma and providing support and therapy for those who have experienced it is crucial in preventing the emergence of future serial killers and murderers. Serial killers and murderers often captivate the public's morbid fascination. These individuals commit heinous acts, leaving a trail of devastation in their wake. While there is no one-size-fits-all explanation for their actions, a significant number of them share a common thread - traumatic childhood experiences, particularly injuries or accidents that left a lasting mark on their mental and physical well-being. In this blog, we will delve into the unsettling stories of British serial killers and murderers who suffered significant childhood injuries, and explore how these events may have played a role in shaping their monstrous paths. Fred West, infamous for his part in the Gloucester House of Horrors case, experienced a traumatic accident at the age of 17 when he fell from a tree and suffered a head injury. This incident left him with severe mood swings and behavioral changes. Experts have speculated that this injury may have exacerbated his already troubled upbringing and contributed to his sadistic tendencies. West's violent acts, including the murders of multiple women, showcased a deep-rooted depravity that manifested after his childhood injury. While not all those who suffer head injuries turn to violence, it is evident that in West's case, this event had a profound impact on his mental state. Dennis Nilsen, another notorious British serial killer, suffered from a head injury as a child when he was struck by a car. Although not immediately life-threatening, this event, combined with his family's isolation and abuse, likely contributed to his later crimes. Nilsen's childhood accident, alongside a challenging upbringing, resulted in feelings of isolation and detachment. These emotions later found an outlet in the horrific murders of at least 12 young men. While not all who suffer from childhood injuries resort to violence, in Nilsen's case, the psychological impact of his accident seems undeniable. Mary Bell, one of Britain's youngest serial killers, had a traumatic childhood marked by abuse and neglect. She suffered an accident at the age of 2, falling from a window, which left her with a severe head injury. This accident could have contributed to her erratic behavior and later, her participation in the murders of two young boys. Mary Bell's case highlights the devastating consequences of childhood injuries and the potential long-term psychological impact they can have, especially when coupled with other traumatic experiences. Ian Brady, one of the infamous Moors Murderers, was struck in the head with a shovel during a childhood altercation. This head injury, combined with a troubled family life, likely played a role in his descent into sadistic violence. Brady and his accomplice, Myra Hindley, tortured and killed several children in the 1960s. The head injury suffered by Ian Brady could have contributed to his already disturbed mindset, eventually leading him down a path of unimaginable brutality. Robert Black, a Scottish serial killer and pedophile, had a traumatic childhood marked by frequent head injuries due to accidents and a tumultuous upbringing in foster care. These early traumatic experiences may have contributed to his psychopathic tendencies, as he later kidnapped and murdered multiple young girls. Peter Sutcliffe, famously known as the Yorkshire Ripper, sustained a serious head injury in a motorcycle accident during his adolescence. This injury coincided with a troubled upbringing, which experts suggest might have played a role in his descent into brutal serial murders, targeting women in the late 1970s. Colin Ireland's childhood was marred by an accident at age seven, which resulted in a severe head injury. His adult life took a dark turn as he transformed into a serial killer, targeting gay men and brutally murdering five individuals. Experts believe that his traumatic childhood experiences may have contributed to his violent tendencies. Levi Bellfield, the man responsible for a series of high-profile murders in the UK, had a traumatic childhood filled with head injuries due to accidents. This, combined with a dysfunctional family, may have contributed to his violent tendencies and later crimes against women. Rosemary West is infamous for her involvement in the murders of at least 10 young women, including her own daughter, Heather. Rosemary endured a difficult childhood marred by sexual abuse at the hands of her father and suffered a head injury in a motorcycle accident at the age of 16. This injury, combined with her early exposure to sexual violence, likely contributed to her later sadistic tendencies and her willingness to participate in her husband Fred West's gruesome crimes. Robert Maudsley, incorrectly dubbed "Hannibal the Cannibal" courtesy of talentless tabloid hacks, experienced a traumatic childhood marked by neglect and abuse. His upbringing was filled with violence and instability, which ultimately led him to become one of Britain's most notorious serial killers. As a teenager, he suffered a head injury in a fall, which some experts believe may have exacerbated his violent tendencies. Kenneth Erskine, also known as the "Stockwell Strangler," committed a series of brutal murders in South London. He had a history of developmental issues and was described as being "different" from a very young age. A head injury sustained in a car accident during his teenage years was thought to have further contributed to his mental instability. Peter Bryan earned notoriety for his gruesome acts of cannibalism. A head injury he sustained during his teenage years in a car accident was later cited as a contributing factor in his violent tendencies. The accident had caused significant damage to his frontal lobe, a region responsible for impulse control and decision-making, which could have influenced his horrific actions. Richard Dadd - While not a traditional serial killer, Richard Dadd's story is a chilling one. As a talented artist in the 19th century, Dadd suffered a head injury during a trip to Egypt. After the accident, he underwent a dramatic transformation, developing paranoid delusions and ultimately committing murder. His traumatic brain injury had a profound impact on his mental state and led to his descent into madness. Michael Ryan - The Hungerford Massacre: The Hungerford Massacre in 1987 sent shockwaves through the UK. Michael Ryan, the perpetrator, had a troubled childhood marked by head injuries and trauma. His father's suicide and a series of accidents left him deeply scarred and potentially contributed to his violent outburst, where he killed 16 people and injured many more before turning the gun on himself. Graham Young, known as the "Teacup Poisoner," was responsible for a series of poisonings in the 1960s. As a child, Young suffered from a mysterious illness, which required numerous hospitalizations. These frequent encounters with death and illness ignited his fascination with toxic substances, setting him on a path towards serial murder. Young's childhood trauma left him mentally scarred and deeply disturbed, ultimately leading to a string of poisonings. John George Haigh, the "Acid Bath Murderer," had a difficult childhood, witnessing his father's affairs and experiencing social isolation due to his stammer. His troubled youth culminated in a near-fatal fall at age 21, which led to head injuries. These events might have propelled him toward a life of crime, resulting in the murders of at least six people, with their bodies dissolved in sulfuric acid. Joanna Dennehy is one of the few female serial killers in Britain. She embarked on a killing spree, targeting men, and later claimed that a traumatic car accident in her youth had altered her personality, making her more prone to violence. This accident potentially played a role in shaping her murderous tendencies. Thomas Hamilton was responsible for the Dunblane school massacre in 1996, where he killed 16 children and their teacher before turning the gun on himself. Hamilton, who struggled with social isolation, survived a serious head injury as a teenager. This incident could have contributed to his mental instability and eventually, his heinous act. Myra Hindley, infamous for her role alongside Ian Brady in the Moors Murders, witnessed her parents' tumultuous divorce. Later, she suffered a severe head injury after a motorcycle accident in her late teens. This event is believed to have triggered her descent into darkness, as she became a willing participant in the sadistic murders of five children. The trauma and brain injury seemed to have heightened her capacity for cruelty. Robert Napper's childhood was marred by an accident that left him with a brain injury. The injury was thought to have triggered his paranoid schizophrenia, which eventually led to a horrifying crime. Napper brutally killed Samantha Bisset and her four-year-old daughter Jazmine in 2005, illustrating the devastating consequences of early trauma. John Duffy's troubled youth was characterized by a serious head injury he sustained during a fall at a construction site. This injury had lasting effects on his mental well-being. He later became a serial rapist and murderer in the 1980s, earning him the nickname "The Railway Rapist." His childhood injury and resulting psychological trauma undoubtedly contributed to his violent actions. John Reginald Christie's childhood was a tumultuous one, marked by a severe fall from a tree, leading to a head injury. This injury, along with his troubled family life, played a pivotal role in his later criminal activities. Christie would go on to commit a series of gruesome murders, including the infamous Rillington Place murders in the 1940s and 1950s. Neville Heath's childhood was marked by tragedy and loss. He lost his mother at an early age and endured a traumatic head injury when he was involved in a car accident. This accident left him with severe headaches and mood swings, which would later contribute to his violent tendencies. Heath was responsible for a string of murders and sexual assaults in the 1940s, earning him the moniker "The Lady Killer." John Straffen's story is a chilling example of how early trauma can set a person on a dangerous path. As a child, he was involved in a serious accident, sustaining a head injury that led to epileptic seizures. These seizures not only affected his mental health but also hindered his ability to control his impulses. Straffen would later become one of Britain's most notorious child murderers, taking the lives of several young girls in the 1950s. Mary Pearcey, a Victorian-era murderer, had a tragic early life. She lost her parents at a young age and suffered a traumatic head injury in a riding accident. Some have speculated that her head injury may have contributed to her descent into madness, culminating in a double murder in 1890 that shocked London. John Childs, the "Essex Boy Killer," had a troubled childhood. He was severely bullied and had an accident that left him with a fractured skull. This traumatic experience caused personality changes and a deep-seated need for revenge, ultimately leading to a life of crime. Childs later murdered three of his tormentors, highlighting the profound impact of childhood trauma on his psyche. Peter Manuel, a notorious Scottish serial killer, had a traumatic childhood. He suffered a severe head injury in a playground accident, which some suggest may have played a role in his later sadistic and violent behavior. Manuel went on to commit a series of heinous murders in the 1950s, leaving a legacy of terror in his wake. Peter Tobin, infamous for his brutal killings, also suffered a traumatic head injury as a child. His early accident, along with a difficult upbringing, played a part in his descent into a life of crime. Tobin's history of violence against women is a stark example of the devastating effects of childhood trauma. George Joseph Smith, known as "Brides in the Bath" murderer, experienced a traumatic childhood accident when he was hit by a tram, which left him with a severe head injury. His crimes were marked by a pattern of marrying and subsequently drowning his wives. The lasting effects of his accident have been theorized to have played a role in his sociopathic behavior. Anthony Arkwright - "The Suffolk Strangler". Anthony Arkwright's teenage years were marked by a traumatic car accident that left him with a severe head injury. He later became "The Suffolk Strangler" and murdered multiple sex workers, possibly influenced by his past trauma. (not to be confused with Steven Wright) Mary Wilson, dubbed "The Merry Widow of Windy Nook," suffered from encephalitis as a child, resulting in severe neurological issues. Her mental health struggles likely contributed to her criminal activities, which included the murder of her husband. Robert George Clements - "The Camberwell Poisoner". Robert Clements' childhood took a tragic turn when he suffered a head injury during a fall at age 10. This accident altered his behavior, and he later became the infamous "Camberwell Poisoner," convicted of poisoning several family members. Stephen Griffiths was a disturbed individual who suffered head injuries during a car crash in his teenage years. These injuries, combined with his troubled upbringing, may have played a part in his later murders and dismemberments in Bradford. Note: in court he wished to be - incorrectly - known as "the crossbow cannibal" as he whoreishly courted fame from the press. Peter Moore, known as the "Man in Black," had a tragic childhood marked by severe head injuries from multiple accidents. Moore's traumatic experiences and head injuries may have contributed to his sadistic murders of men in North Wales. His crimes were especially gruesome, involving torture and dismemberment. John Justin Miller, dubbed the "Essex Monster," had a traumatic childhood marked by a significant head injury in a car accident. This accident may have played a role in his later criminal activities, which included rape and murder. Miller's life is a stark example of how early trauma can lead to a life of violence. Beverly Allitt, also known as the "Angel of Death," suffered from a severe head injury in her early life. This, coupled with her Munchausen syndrome by proxy, contributed to her poisoning and murder of several children in a UK hospital. Robert Mone and Thomas Walker, who were responsible for the "House of Blood" murders in Glasgow, both had traumatic childhoods marked by severe injuries. Their upbringing, coupled with their shared mental instability, led to their violent crimes. David McGreavy, also known as the "Monster of Worcester," had a history of head injuries from childhood accidents. These injuries, combined with a tumultuous upbringing, contributed to his horrific murders of three young children in 1973. Amelia Dyer, one of Britain's most notorious baby farmers, had a troubled childhood marked by an accident. As a child, she suffered a head injury from a fall, which is often cited as a contributing factor to her later crimes. Dyer would go on to murder infants left in her care, a crime rooted in her past trauma and mental instability. Michael Lupo, known as the "Hampstead Heath Vampire" and "the wolfman" experienced a traumatic head injury as a teenager. The injury reportedly changed his personality and may have contributed to his gruesome murders in the 1980s. Patrick Mackay experienced a troubled childhood, including an incident where he was hit by a car. This early trauma was followed by a life marked by mental instability. Mackay went on to become one of the most notorious British serial killers in the 1970s. John Childs - "The Granny Killer", who terrorized the elderly population in the 1970s, experienced childhood head injuries. His violent tendencies may have been exacerbated by these early traumas, which eventually led to a series of brutal murders. Steve Wright - "Suffolk Strangler". Steve Wright's troubled upbringing included a head injury from a motorcycle accident in his teenage years. The trauma may have contributed to his later sexual crimes, as he went on to murder five women in Ipswich. Donald Neilson, infamously known as the "Black Panther," committed a series of violent crimes, including the murder of heiress Lesley Whittle. In his youth, Neilson sustained a head injury during a fall, which some speculate could have had a lasting impact on his cognitive and emotional development. Colin Stagg was falsely accused of being the "Rachel Nickell killer" in a highly publicized case. Stagg had a difficult childhood and was the victim of a severe dog attack in his youth. Although he is not a serial killer, the media scrutiny and false accusations he endured had a significant impact on his mental well-being. The lives of British serial killers and murderers are often shrouded in darkness, but it is important to examine the role that childhood injuries and traumatic events play in their descent into violence. While it is essential to remember that not everyone who sustains a childhood injury becomes a criminal, these cases illustrate that early trauma can, in some instances, intersect with preexisting emotional and psychological vulnerabilities, pushing individuals toward horrific acts. Understanding the complex interplay between childhood trauma, mental health, and criminal behavior is a crucial step in preventing and addressing such atrocities. It also underscores the importance of providing support and intervention for those who have experienced traumatic events during their formative years, as this may help prevent a future marred by violence and suffering.

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, all set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY:

On Friday 27th of March 1959 at 2:50am, Graham Osborn man was found slumped against the railings at 117 Piccadilly. Later dying of his wounds, no-one knew why he was there, few knew that had happened and no-one knew who had attacked him or why. And although the Police would bring his killers to trial, this little-known case would only lead to more questions than it answered.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location is marked with a teal coloured exclamation mark (!) near the words 'The Green Park'. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other maps, click here.

SOURCES: This case was researched using some of the sources below.

MUSIC: