Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast #82: Sulphuric: 6 - Henrietta Helen Olivia Robarts Durand-Deacon24/12/2019

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within one square mile of the West End.

EPISODE EIGHTY-TWO:

On the evening of Friday 18th February 1949, serial-killer John George Haigh murdered his sixth and final victim Henrietta Helen Olivia Robarts Durand-Deacon, also known as Olive at his storeroom at Leopold Road. Six people had been murdered, as English Law states that “corpus delicti – with no body, there can be no crime”, having dissolved their bodies in acid, he knew he could literally get away with murder… but Haigh had made a fatal error.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

Ive added the location of The Onslow Court Hotel at 108 Quen's Gate where John George Haigh lived for the last four years of the murders and where he met Olivia Durrand Deacon. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, Paddington or the Reg Christie locations, you access them by clicking here.

here's two little videos for you to enjoy with this episode; on the left is Wandsworth Prison (still a prison today) where John George Haigh spent his final days and where he was executed, and on the right is The Onslow Court Hotel in South Kensington where Johnny lived and where he met Olivia Durrand Deacon, his final victim. These videos are links to youtube, so they won't eat up your data.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This series was researched using the original declassified police files held at the National Archives, the Metropolitan Archives, the Wellcome Collection, the Crime Museum, etc. MUSIC:

SOUNDS:

TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: PART SIX OF SULPHURIC.

Johnny Haigh seemed such an unassuming little fellow; small and slight, neat and polite, and being just a few weeks from forty – blessed with a boyish face, dimpled cheeks and an unbroken voice - as he nibbled his toast and supped his tea, the quiet little choir-boy whose mummy had dressed him in bow-ties was still easy to see… but not the monster that he claimed to be. For the last few hours, the four men had sat in the stuffy cramped confines of Interview Room Three of Chelsea Police Station, and as Chief Superintendent Barratt, Divisional Detective Inspector Symes and Detective Inspector Webb listened, little Johnny Haigh candidly recounted his callous crimes with the calmness of a man for whom murder was routine. And as each delicious detail tickled him, his feeble moustache bristled, but behind the dark dots of his marble-like eyes, there was nothing. (Haigh) “I have made some statements to you about the disappearance of Mrs Durand-Deacon. The truth is, we left the hotel together and she was inveigled by me into going to Crawley. Having taken her into the store-room at Leopold Road, whilst she was examining some paper for use as fingernails, I shot her in the back of the head and disposed of her in a tank of acid”. Having befriended the McSwan family and the Henderson’s, assumed their identities, inherited their estates and drained their assets, all five had mysteriously vanished and almost no-one had noticed. Any investigation would prove fruitless; years had passed, evidence was sold, and with no fingerprints or witnesses, basing his murders on the legal loophole that (Haigh) “corpus delicti - with no body, there can be no crime”, all that remained of his victims was a yellowy-green sludge. And so, cocky in his confidence, having already confessed to five perfect murders, John George Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers would now confess to a sixth; the how, the where and the when, every single detail… but without a body, the Police could do nothing. (Interstitial*) Give or take a few minor mishaps, his first five murders had been a doddle and his sixth would be easy-peasy, but unlike the pitiful scraps he had been tossed having popped-off the supposedly wealthy McSwan’s and the Henderson’s, this time, Johnny would hit the jackpot… and not a moment too soon. Johnny was broke! Again! Having first fleeced the fortunes of the McSwan family and blown every penny in two and a half years, as the Henderson’s deaths had netted him a hefty £7700 (almost a quarter of a million pounds today), this should have been enough money to last a lifetime… only after just eight months, Johnny squandered the lot, and worse still, his bank account was overdrawn. How? Don’t ask! He didn’t drink, barely smoked, didn’t do drugs and – described by his on/off lady friend as a “bit of a cheapskate” – although he wore sharp suits, drove fancy cars and ate in the best eateries, that was all just for show, as his idea of a good date was tea, toast and scrambled egg. But then, nobody’s perfect. Of the three vices Johnny had, all would bleed him dry; as a bad gambler he couldn’t tell a dead-cert from an old nag; as a wannabe entrepreneur, he couldn’t see a done deal from a dodgy dud; and – most bafflingly of all - although he never had an ounce of empathy for anyone but himself, this working-class boy aspired to be accepted by those he secretly despised. By the first week of February 1949, being neck-deep in debt and having bounced his last cheque, owing six weeks back-rent at the Onslow Court Hotel who had told him to “pay-up or get-out”, the middle-class reputation Johnny had cultivated was now in tatters and his name was becoming mud. Business was bad. Nothing came of the silent jackhammer, the needle-threader, the toy rocking horse, the battery powered fan, or the other silly ideas he had no skills to build, and with Edward Jones sick of his so-called partner’s stupid schemes, Johnny’s only other means of income had come to an end. As hard times bit hard, having sold Archie’s Lagonda and Saloon 12, shamefully this supreme swindler (who’d been half way to becoming a millionaire) scuttled back to his old tricks, by illegally refinancing his Alvis for just three hundred quid, a petty scam he last did a decade ago, only now, being so in love with living the high life, this pittance wouldn’t last him a day. But for Johnny there was no going back. He’d been poor, broke, hungry and homeless, and he didn’t like it, not one jot. For this boy born in the stark austerity of the Plymouth Brethren, there was nothing finer than sleeping on Indian linen sheets and taking tea and tiffin in the Tudor Room of the Onslow Court Hotel. It was civilised, cultured, sophisticated and – as one of its few male residents - being swarmed by a wealth of lonely widows, easily ensnared by the cheeky charms of a harmless man who (even during rationing) could slip his girl’s a little treat - like tights, bags and silks (just ignore the scorch marks) – oh yes, here he was adored… but taking tea with Johnny was like putting a famished shark in a paddling pool. Since Christmas, wreaking with desperation, he had struggled to lure several ladies to their deaths at Leopold Road, and now he was out of money, out of time, out of luck… but not out of persistence. (Haigh) “When I discovered there were easier ways to make a living, I did not ask myself whether I was doing right or wrong. That seemed to be irrelevant. I merely said “this is what I wish to do”. And as a means lay within my power, that was what I decided… if you’re going to go wrong, go wrong in a big way. Go after women – rich old women who like a bit of flattery. That’s your market”. Unlike the pitiful pay-out he had been bequeathed from his old dead pal Mac McSwan and his fleet of pinball parlours, the day Johnny met Mrs Durand-Deacon, he knew had hit the jackpot… Mrs Durand-Deacon was blessed with an impressively regal name which reflected her upper-middle class status, born on 28th February 1880, she was christened Henrietta Helen Olivia Robarts Fargas, although for brevity’s sake, she preferred to be called “Olive”. As the first of five children to Henry, a prominent solicitor and Helen, a solicitor’s wife, raised among the royal parks in the wealthy borough of Richmond, shielded by the ornate wrought-iron gates of an affluent country villa with private tutors, four servants and a nurse, the upbringing of Olive could easily be described as privileged, and although she had money, above everything else, she had morals. Being smart and fiercely independent, Olive was protective of her younger siblings; Nigel, Angela, Fred and Esme, and as a big sister - in every sense - being five foot ten and fourteen stone, as a stoutly built and strong-willed girl, she stood-up to bullies, shielded the weak and had a fire in her belly to fight for the rights of those less fortunate; not an easy a feat in an era where women were second-class citizens. Having rejected the shackles of marital subservience, for Olive, the early 1900’s was a time to fight… By the death of Queen Victoria - one of Britain’s wealthiest and most powerful women – the average woman had less rights than a horse; education was limited, careers were denied, prospects (beyond marriage and babies) were bleak, and denied the right to vote, women had no say on their own lives. In 1903, infuriated at the ineffective women’s groups whose crusades culminated in a strongly-worded letter to the all-male British government, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Sylvia and Christine set-up The Women’s Social and Political Union; a small but powerful group who through “deeds not words” would fight and (if needed) die to give women the right to vote - one of their group was Olive. Seen as little more than weak women, the government grossly underestimated the passion with which these women would fight, refusing to be silenced and unfazed by the threat of arrest, in order to draw attention to their cause, they relied on new tactics, what they referred to as “direct action”; whether by heckling, threats or protests, hunger-strikes, suicides and even bombs. Under the name of ‘Mrs Drew’, Olive was unabashed about her own direct actions; over three years, she was expelled from the Albert Hall for shouting-down the First Lord of the Admiralty, she publicly harassed Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and Cabinet Minister Winston Churchill as they strolled along Whitehall and being a staunchly vocal and physical supporter of women’s rights, she took part in the Black Friday protest of 1910 and two city-wide campaigns of targeted criminal damage across the West End in November 1911 and March 1912 - the second of which would land Olive in prison. On Monday 4th March 1912 at 8am, The Women’s Social and Political Union congregated in Parliament Square for what their invite implied would be speeches by well-known suffragettes, but in truth, this rally of little women was nothing but a cunning ruse. As the speeches began, in a simultaneous attack, over 150 women armed with hammers, stones and clubs smashed shop windows right across the West End. Olive and her pal, the radical suffragette Maud Joachim broke six panes of glass at a jewellers and tea-shop on Regent Street, causing £32 worth of damage, and although the press initially dubbed this as an act of mindless violence, it was actually a very calculated political statement, designed to prove the government cared more about broken windows than a woman’s life… and they were right. As one of the 126 women arrested, Olive spent five days at Holloway Prison, was fined £50 and was bound-over for one year, but it was a small price to pay, as vowing to fight on until every last women, regardless of class, wage or education had the right to vote… by 1928, they had won. On 13th August 1918, 38 year old Olive married Reginald Durand-Deacon, a Captain in the Gloucester Regiment who later became a wealthy London lawyer, and although (a little late in life) she had finally found true love, standing true to her beliefs, her life would be good but her fight would never be over. In short, unlike his other victims – a thin timid drip, a weak pair of old recluses, a bankrupt impulsive boozer and a bed-bound neurotic - Mrs Durand-Deacon would be no push-over. Compared to Johnny, she was taller, heavier, stronger, bolder and a real force-of-nature who never let a mere man boss her about. But as Johnny knew, every victim had their fatal flaw, and hers… was that she was lonely. After twenty years of wedded bliss, on 25th January 1938, Reginald died. With a will of £5800 (just over £360,000 today) and no debts or dependents, her financial stability was assured, but a large pile of money is a poor substitute for the love, warmth and companionship of her beloved husband. For the last eleven years of her life, Olive never remarried, and although she was lonely, she was never alone… …which was bad news for Johnny. In fact, almost everything about Olive Durand-Deacon made her unsuitable for his murderous plan. Olive was a well-known face in South Kensington high society, who was liked by everyone and was an active participant in groups such as the Six Points women’s suffrage, the Francis Bacon Society, Christian Science and Solicitor’s & Artists Benevolent Fund, all of which she gave sizable donations. Olive was predictable; a precise and punctual lady who disliked surprises and rarely deviated from a schedule she openly discussed with her closest friend Constance Lane, and hating waste, she always informed the staff at the Onslow Court Hotel if ever she planned to be away (which was rare) or late. Olive was easy-to-spot; as a tall, broad and regal looking lady, with immaculate make-up, who turned heads in her royal blue dress, black Persian lamb coat, large black hat, tortoiseshell spectacles and a bright red handbag. And as a lover of exquisite jewellery – who was never without her twin-set of pearl necklaces, pearl studded earrings, 18 carat gold watch, five rings (studded with rubies, sapphires and diamonds) and a large Russian crucifix on a gold chain – whenever she walked, she sparkled. But worse still for Johnny, her disappearance would be entirely out-of-character and unexpected… …Olive was an honourable lady; she had no vices, debts or enemies, she lived sensibly, spent frugally and although she tipped well, she never withdrew more than £5 a week to cover her needs. And with no psychological issues, as an older overweight lady, she had no major medical problems, except for gall-stones which gave her a mild stomach ache and a new set of dentures she had recently had fitted. As his next victim, she was entirely unsuitable… …only Johnny was blind-sided by one bright shining detail. Olive was rich, very rich, as having been bequeathed a small fortune by her late husband, as a savvy businesswoman and a shrewd investor in her own right, Olive had turned this £5800 into £37000 – a lonely widow who today would be worth £1.2 million pounds. To Johnny, he had hit the jackpot, and all it took was a little flattery. (Interstitial*) (Haigh) “She was inveigled by me into going to Crawley. Having taken her into the store-room at Leopold Road, whilst she was examining some paper for use as fingernails, I shot her in the back of the head. Following that, I removed her coat, jewellery and disposed of her in a tank of acid. Oh, I should have said that in-between, I went round to a cafe for a cup of tea and scrambled egg”. But she was so strong, so confident and so feisty? She was a fiery independent woman who harangued Prime Ministers, shouted down an Admiral, smashed shop windows and scraped in the street with the Police, where-as little Johnny Haigh, the skinny little weasel had repeatedly lied in his so-called confession, so was her death really that simple? (BANG, SLUMP, FIZZ) Well, yes, it was. With his first five deaths a doddle and his sixth easy-peasy, having learned his lessons, murder really had become routine for Johnny… and yes, as always, he made a few cock-ups here-and-there… only this time, being so broke and desperate to sink his claws into Olive’s fortune – with his cocky calmness replaced by an impulsive recklessness – his mistakes weren’t just big, they were bloody stupid. The killing Mrs Durand-Deacon wasn’t a well-though-out plan but a last-minute decision… On Monday 14th February 1949, four days before her death, as Olive took lunch in the Tudor Room with her friend Gwendoline; overhearing the ladies discuss a lack of suitable alternatives to artificial fingernails and offering to mock-up a solution, Johnny invited Olive to his workshop in Crawley. It seemed inconsequential, but several witnesses heard the killer, lure his victim, to the murder location. On Tuesday 15th February, Johnny ordered thirty gallons of sulphuric from Alfred White & Sons, being broke and his cheques having bounced, and although their relationship had fractured, he was forced to loan the cash off his unhappy business partner Edward Jones, and get Thomas Davies to deliver it. On Wednesday 16th, as a years’ worth of wind and rain had rusted the steel drums he had stashed in the yard, yet again, unable to replace or repair either, he was forced to order a new one, but with no money to pay the bill, he didn’t, and for days afterward, risked a bailiff being sent round to collect it. And yet, his worst mistakes were yet to come – this time, his crime had witnesses, a lot of witnesses. Friday 18th February 1949 was Olive’s last day alive. As usual, as she took tea with Constance Lane in the small but tightly-packed Tudor Room, Olive said “I’m going down to Mr Haigh’s place in Crawley where he experiments on different things”, her appointment was at two-thirty and the time was ten passed two. This exchange was overheard by Constance, several residents and three waitresses. At 2:10pm, Hilda Kirkwood (the hotel’s bookkeeper) witnessed Johnny leave via the front door, cross Queen’s Gate, enter his garage at Manson Mews and drove two and a half miles east in his dark-blue Alvis (registration plate BOV463), which was odd, as he was meant to meet Olive in fifteen minutes. At 2:15pm, distinctively dressed in a royal blue dress, a large black hat, a black Persian fur coat, two pearl necklaces and a bright red handbag, Hilda watched as Olive hailed a taxi and headed in the same direction, to the Army & Navy Stores on Victoria Street where Olive purchased a set of false nails. His plan was simple, as before, by meeting in a pre-arranged place, Johnny could ensure he was never seen with any victim on the day they died. Only having picked-up Olive, he was spotted… twice. First at 3:45pm, as Johnny’s 20hp Alvis trundled passed Maurice Laudauer’s garage at Povey Cross at a sedate 35mph, the owner (who knew him well having serviced his car on many occasions) saw Johnny, in broad daylight, driving his Alvis towards Crawley, with a lady who fitted that description. And second, a little after 4pm, with her gall-stones giving her gip, Olive needed to use the loo, so they stopped-off at The George; a local hotel, where (for the last five years) Johnny had often ate and slept, and having politely asked “Would you don’t mind if I use your bathroom?”, the manager Hannah Caplan would later positively identify Mrs Durand-Deacon... and Johnny Haigh; together, in Crawley, just three streets from Leopold Road and a few moments before her death. (BANG, SLUMP, FIZZ). With Symes & Barratt having stepped away a while ago, as Haigh concluded his confession to Detective Inspector Webb, although his mouth grinned, the soulless glare of his cold dead eyes gave away nothing, “Mrs Durand-Deacon no longer exists. She has disappeared completely and no trace of her can ever be found. How can you prove murder if there is no body?” And with that, the callous killer slurped his tea. He loved to toy with this simple copper, knowing his intellect was vastly superior… …but there was one thing Johnny didn’t know - the Police were one step ahead. Being a master of silence and subtly checking his watch, Webb waited till Johnny had ran out of things to say and segued into small-talk, Haigh asked “so, where are the other two?”, suitable baited Webb replied “Well, they shouldn’t be very long now, they’ve got a fair way to come”, leaving that little morsel dangling on a hook, (Haigh) “They’ve been a long time, haven’t they?”, and with that Johnny fell into Webb’s trap (Haigh) “Where are they coming from?” to which Webb replied “Oh, they’ve been down to Crawley”. Johnny didn’t react; no smile, no blink, no wince, just a single solitary gulp. But what could they prove? Nothing. For Johnny, the evening of Olive’s death was like any other (Haigh) “disposal had become automatic by then. I am not aware of any remorse. It was a fatiguing business getting a fourteen stone carcase into an oil drum on one’s own, it took me two hours”. So hungry and tired, he had tea, toast, scrambled egg, a good night’s sleep, and the next morning, pumped the drum four-fifths full of acid and left. There was blood on the walls, a handbag on the floor, tortoise-shell spectacles on the bench and a dead body dissolving in a drum, but with so much money to spend, Johnny was gone. And yet, before his cunning subterfuge of writing letters to lawyers and siblings began, it all took an unexpected turn… On the afternoon of Sunday 20th February, with the usually punctual lady now missing for two days, Constance Lane, a long-term resident at the Onslow Court Hotel walked into Chelsea Police Station and reported her close friend – Olive Durand-Deacon - as missing… and she was aided by Johnny Haigh. Eager to limit the damage, as Police Sergeant Dale took down Olive’s particulars, Johnny vainly barked “You have written down Mrs Lane’s name and address, but you haven’t asked for mine”. A decision which would prove fatal, as being so prominent in South Kensington’s high society, her disappearance made the papers… and so did Johnny’s name… a detail which didn’t go unnoticed by Arnold Burlin. On Monday 21st, three days had passed, but the body hadn’t dissolved, (Haigh) “I returned to Crawley to find the reaction almost complete, but a piece of fat and bone was still floating in the sludge”. Being taller than Amy & Rosalie, having pumped the drum four-fifths full of acid, just like Archie, although her flesh, muscles and bones had dissolved into a black acrid soup, parts of her left foot still bobbed about on the thick sticky surface of yellow-green gloop. (Haigh) “I emptied off the sludge with a bucket and pumped a further ten gallons of acid into the tank to decompose the remaining fat and bone”, having tossed in her red handbag for good measure. A day later, “I dumped it in the yard”, and with that, the body was gone, evidence was destroyed and Mrs Durand-Deacon had vanished (Interstitial*). …but the Police were closing in. As a matter of routine in a missing person’s case, WPS Alexandra Lambourne questioned everyone at Onslow Court; their answers were solid, but one resident stood out; as being too eager to tell his side of the story, although this neat little man came across as harmless, something about him caused her skin to crawl, and unhappy with his answers, she alerted her boss - Detective Inspector Albert Webb. Across the week, Johnny volunteered several statements in connection to her disappearance, but with his details vague, his facts shifting and his eyes cold and unemotional, having pulled his criminal record - although he had no history of violence – the detectives were in no doubt that they were dealing with a fraudster, a forger and a professional liar, so treading carefully, they brought him in for questioning. On Monday 28th February at 4:15pm, when asked to assist the Police once more, Haigh exclaimed “I’ll do anything to help you” and was driven to Chelsea Police Station… but instead of being free to speak, as Webb awaited his colleagues’ return, for the first two hours, all they did was sit and wait in silence. Exuding the calmness of a man who knew he would never be caught, Johnny supped tea, nibbled toast and even snoozed, but the delay was deliberate, and being so desperate to show-off just how clever he really was, although he would brazenly confess to his six perfect murders… the wait gave Barratt and Symes time to examine the storeroom at 2 Leopold Road. Given permission by Edward Jones to break the lock, everything was a Johnny had left it a few days prior; his clean-up wasn’t even slap-dash, it was non-existent, but he knew he didn’t need it to be. With the later investigation headed-up by Home Office pathologist Dr Keith Simpson and Detective Chief Inspector Guy Mahon; inside, they found three carboys of acid, an Enfield Mk1 revolver, eleven rounds of .38 calibre ammunition (three spent), a rubber apron, a set of rubber gauntlets, an Army-issue gas-mask, several items marked with a large monogrammed H, ten strips of red cellophane (believed to be a prototype for artificial fingernails), a broken monocle, a spatter of bloodstained whitewash removed from between two windows, an attaché case full of passports, driving licences, identity cards, ration books and marriage certificates in the names of William Donald McSwan, Donald McSwan, Amy McSwan, Archibald Henderson and Rosalie Henderson, and outside in the yard, three 40 gallon steel drums (two badly rusted and one nearly new but empty and dry) and a large quantity of yellowy-green sludge. It was a wealth evidence, but it was all circumstantial, and it wasn’t a body. From the basement at 79 Gloucester Road, they recovered some unspecified sludge from inside the manhole and an old worn axe, gifted by Johnny to the estate agent, Albert Marshall, but not a body. From Room 404 at the Onslow Court Hotel, they found a large stash of personal possessions belonging to all six victims, including Mac’s typewriter, Archie’s suits, every piece of forged paperwork relating to the theft of their estates, a shopping list written in Johnny’s handwriting for (Haigh) “a drum, acid, stirrup pump, gloves, apron, rags, cotton wool, red paper etc”, and amongst his dirty linen they found a bloodied shirt. And although he fully confessed (Haigh) “that must be Mrs Durand Deacon’s blood. I was wearing that shirt when I shot her”, again, it circumstantial evidence, but wasn’t a body. After a painstaking examination of the yard at Leopold Road, having sieved 400lbs of soil, the Police found the smashed frames of Olive’s spectacles and the plastic handle of her red handbag, as well as several fragments of bone identified as the left foot of an elderly female, the broken pieces of Olive’s dentures (identified by her dentist) and amazingly even one of her gallstones. But once again, it wasn’t a body, in fact, with everything having been dissolved into an unrecognisable stew, these random bits of a dead woman were as close as the Police ever came to finding the remains of Mrs Durand-Deacon. When shown all of the legal letters he had forged, although Johnny cockily crowed “yes, I wrote all of the signatures”, even going so far as to quip, “I signed Mac’s name, I remember I didn’t make a good job of it, instead of Donald, I write Ponald”, they could only arrest him for fraud but nothing more. Even his diary, in which he had celebrated each killing with an initial “A is for Archie, R is for Rose”, knowing that “with no body, there can be crime”, as circumstantial evidence, it meant nothing. (End) He had given the Police everything, and having confessed to the murders of six innocent people – the McSwan’s, the Henderson’s and Mrs Durand-Deacon - all of whom had vanished completely, John George Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers would never be convicted. (Interstitial*) …or so he thought. Across his six (supposedly) perfect murders, little Johnny Haigh had made a lot of mistakes, many of which he had miraculously got away with, and although many were big, they weren’t the biggest, as back in Lincoln Prison, on the day he had concocted his murderous plan, he had made a fatal mistake. Back in Interview Room Three at Chelsea Police Station, bored of waiting, Johnny impatiently pressed (Haigh) “What are they doing now? Symes and Barrett I mean”. (Webb) “Well John, I don’t really know, but I should imagine they are working hard in order to get you hanged”, (Haigh) “Hanged, what on earth for?”, (Webb) “Oh, you know very well that they only hang people for one reason in this country, don’t you John?”. And he did… but having once read in a law-book about Corpus Delicti, Johnny knew (Haigh) “You can’t prove that I murdered anybody… you can’t prove a murder without a body”. To which, as his trap snapped shut, Webb retorted (Webb) “Oh yes you can…” and as Webb listed two trials off the top of his head, with that cocky grin firmly wiped off his smug little face, Johnny gulped. Johnny was right though, “Corpus Delicti, with no body, there can be no crime”, but his mistake was to assume that by “body” the law meant a human body, but it doesn’t, it means a “body of evidence”. All the Police needed was enough circumstantial evidence to prove where the victim had been, how they had died and been disposed of and – more importantly - who had killed them, and having confessed to six murders, including Mrs Durand-Deacon’s - Johnny had given the police everything. On 2nd March 1949, Johnny was charged with the murder of Henrietta Helen Olivia Robarts Durand-Deacon, to which he replied “I have nothing to say”. The irony lost on him, as many-moons before, he had boasted to his cell-mate “who can tell if a murder has taken place if a person completely disappears? Only the murderer would know and if he kept his mouth shut, he would be safe”. On 18th July 1949, at Sussex Assizes, he pleaded his innocence, but after a two-day trial and having deliberated for just seventeen minutes, a unanimous jury found him “guilty” and he was sentenced to death. On Wednesday 10th August 1949 at 9am, taking just seven seconds from the opening of the cell door to his little torso dangling from a taut hemp rope, as seasoned executioner Albert Pierrepoint perched the tiny trembling monster on a chalk ‘x’ - granted no last words, no final requests, no quick cigarette, no speeches, no bullshit, not even time for tears – with his last ever sight blocked by a thick white hood, as his skilled slayer pulled the lever, the trap doors parted and as his little body plunged seven feet and four inches into a dark cold void, as the hemp rope tugged tight, the top two vertebrae of his neck snapped to the right and little Johnny Haigh was dead. And with that, the killing-spree of John George Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial killers finally (for the very last time) came to an end. (End) But was his death really that simple? (Rope/Pull/Creak) Well, yes, it was. (Interstitial*) OUTRO: Friends. Thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile, that was the final part of Sulphuric; the true story of John George Haigh, with the omnibus editions of this series and a special Q&A episode rolling out next week, to mark the end of the season. A big thank you to my new Patreon supporter – Mir Razavi – as well a big thank you to Julie at Nostalgia Knits for sending me the lovely hand-knitted sock, very cosy, and April McLucas and Emily Lock for the kind donations sent via the Murder Mile website. I promise you, it will be spent on beer and cake. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER *** The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, therefore mistakes will be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken. It is not a full representation of the case, the people or the investigation in its entirety, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity and drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, therefore it will contain a certain level of bias to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER ***

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards 2018", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk

0 Comments

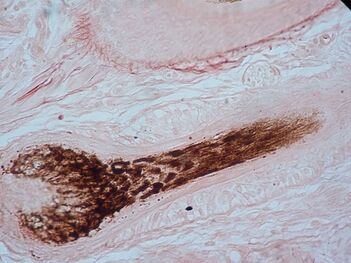

Human Hair: What can a single strand of human hair tell Crime Scene Investigators / Pathologists?20/12/2019

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

What can a single strand of human hair tell crime scene investigators and pathologists?

We’ve all seen it; a cop pulls out a pen, uses it to pick up a single strand of hair, pops that hair into an empty crisp packet, takes it to be boys down the crime lab and boom, the victim is identified. But is that possible, can you get a complete DNA match of a victim or perpetrator from a single thread of human hair? No. You can’t. Currently, it is not possible to identify a person by a single strand of hair, although it is a vital piece of evidence in any enquiry. You can learn a lot from a single strand of human hair, as (unless it’s cut) a human hair normally grows for up to two to six years before it falls out, so you can determine some details: what racial group a person is from (whether European, Asian or African), their hair colour (whether natural or dyed), what chemicals, toxins or heavy metals they’ve been exposed to, the types of foods they eat, possible diseases, genetic disorders, health issues, and if they smoke, drink or do drugs. Gulp! If you’re worried… the drugs which can be tested includes cannabis, cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, methamphetamines, benzodiazepines, methadone, ketamine, most prescription drugs, antidepressants, neuroleptics, steroids and GHB, all from a single strand of hair. And while a urine test will reveal if you’ve used drugs in the last several days, hair testing (depending on the sample) can show if you’ve used drugs over the past 3 months. On average, a person sheds 100-150 strands of hair a day, and although the hair shaft contains some mitochondrial DNA – this DNA is easily degraded by bacteria, fungi, ultraviolet light, bleaches, dyes and the weather, rendering it useless for testing – but it’s actually the root pulp at the end of the shaft which contains the nDNA (nuclear DNA), which is vital for identifying a person. Sadly, the hairs we shed, do not contain root pulp, but they do if they are yanked out in a violent struggle. The problem is that even this nDNA found in the hair’s root quickly degrades when exposed to light, moisture or heat, making it almost useless (but not entirely useless) for identification, so the best hair strands for DNA testing are those pulled directly from the victim or perpetrators’ head with the root pulp still attached, prior to testing, and in order for the laboratory to accurately determine a person’s identity, they wouldn’t need one single hair, they would need at least one hundred. So, the next time you see a TV detective picking up a single eye-lash with their tweezers and getting a match to a known felon within an hour, call “bulls**t”, and check the DVD extras to see if there’s an additional scene where he spends fifty-two days on his hands and knees, scouring the floor for ninety-nine more and praying the felon has a genetic disorder, so unique, they named a disease after him. So why am I bald? Nature’s been cruel to me, that’s all.

If you found this interesting? Check out the Mini Mile episodes of the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast, or click on the link below to listen to an episode.

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards 2018", and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Here's another rather mundane letter written by a serial killer, which willmgives you a different and more interesting insight into them as a person.

This week, we have two different letters written by American serial killer John Wayne Gacy. As a bit of background; Gacy was a man with two distinct lives; on the one hand he was professional contractor, a community volunteer, a business man and a children’s entertainer who dressed as “Pogo the Clown”, and on the other side, he raped, tortured and murdered at least 33 teenage boys and young men between 1972 and 1978, and buried their bodies under the crawlspace of his home. The evidence against him was overwhelming to say the least. Which is why this first letter is so fascinating, it’s a typed letter, by Gacy. It’s undated but appears to have been sent in the early 1980’s, whilst serving on Death Row and awaiting his appeals and was sent to Mr Luis Kutner, Attorney at Law in Chicago. "Dear Mr Kutner. I have recently read about you in the newspapers and wondered if you might be interested in working on my case, at a point of Post Conviction. I have included a clipping on my appeal, while I feel I have good issues, I don’t feel I will get justice in the Illinois courts, because of public pressure and mass publicity surrounding my case. The state appellate defender is handling my appeal at this point, but may not be when I get to Post-Conviction. I was railroaded to where I am now on Death Row, not only by incompetent counsel, but by constitutional law, judicial misconduct and Prosecutors misconduct along with procedural errors. Since you’re as famous as I am infamous, and the vetos you have behind you, I wonder if you would handle the case of a mass murderer who is not one, but can’t seem to get anyone to look at the facts instead of mass publicity, fantasy and state theories. And now in the courts with political pressure. If your interested, I would like to hear from you one way or another, and maybe be able to fill you in on more of the facts so that you would see what I have to work with. I am told that if you would put all of the facts in my case into a computer (ooh) along with all the Illinois law, my case would be thrown out, as there is no evidence to tie it all together. I have been made into a media monster, through mass publicity and the facts seem to just go right out of the door. Thanks for taking time to read this. Look forward to hearing from you. Yours sincerely. John Wayne Gacy" Yes, John Wayne Gacy, you’re absolutely right, put all of the facts to do with the 33 dead bodies who were mysteriously found under your house and the entire US legal system into a computer, which in that era would have been at best a BBC Micro with the computing power of gnat with an abacus, you could press ENTER and it would print GACY IS INNOCENT. Case closed. And secondly, is a handwritten letter, by Gacy, dated 6th May 1994, it is signed John Wayne Gacy and was sent just four days before he was executed. It’s on headed paper, and has at the top (in red ink) “John Wayne Gacy, N00924, Lock Box 711, Menard, Illinois” and as a tag-line “Execution… revenge for a sick society!!!”. Given what we know about him, know this, the letter is written to an unnamed boy who Gacy was corresponding with whilst on Death Row, having murderer young boys his age. “Hi Ho. Hey it was nice talking with you, and keep up with a positive attitude. I understand what your going through with your parents splitting up. But just remember, it’s not your fault, grown-ups do crazy things, but it doesn’t mean they still both don’t love you. You have to accept things you can’t change, change the ones you can, and always think positive for yourself as you have a lot going on for you. I enjoy your letters. I’ve enclosed some art work of mine. Take care for now. Best regards. Your friend up north. John Wayne Gacy”.

If you found this interesting? Check out the Mini Mile episodes of the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast, or click on the link below to listen to an episode.

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards 2018", and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within one square mile of the West End.

EPISODE EIGHTY-ONE:

In the evening of Thursday 12th February 1948, John George Haigh lured Rosalie Henderson (a bed-bound depressed neurotic) to her death, inside the storeroom at Leopold Road, where he had murdered her husband, just a few hours earlier. As with the other four murders, her death and disposal was pretty simple... but something would go horrible wrong.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

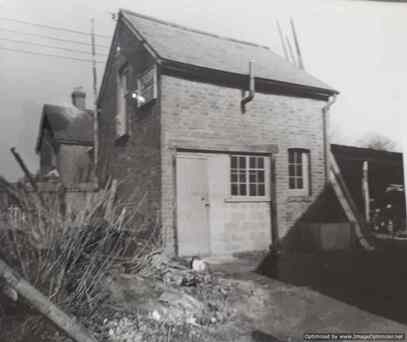

The location of the storeroom in Giles Yard, 2 Leopold Road in Crawley where Archie & Rosalie Hendeson were murdered and their bodies dissolved in acid is marked with a green dot. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, Paddington or the Reg Christie locations, you access them by clicking here.

Two little videos for you to enjoy with this episode; on the left is 2 Leopold Road in Crawley, the site of the storeroom where John George Haigh murdered and dissolved the bodies of Archie & Rosalie Henderson and Olivia Durrand-Deacon (now a nice house) and on the right is 16 Dawes Road in Fulham, former Doll's Hospital toy shop and home of the Henderson's.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This series was researched using the original declassified police files held at the National Archives, the Metropolitan Archives, the Wellcome Collection, the Crime Museum, etc. MUSIC:

SOUNDS:

TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: PART FIVE OF SULPHURIC.

To Johnny, murder had become almost routine, an unemotional moment as common as withdrawing cash, only with the simple transfer between accounts sullied by that tiresome annoyance – people. (Haigh) “I met the Henderson’s by answering an advertisement for the sale of 22 Ladbroke Square. I disposed of Dr Henderson in the storeroom at Leopold Road by shooting him in the head and put him in a tank of acid”. With the doctor dead, the assets should rightfully be his, but in his way was a wife. Rosalie Henderson was a feisty angry neurotic; doped-up on sleeping pills, drowsy with drink and bed-bound in a Brighton hotel, who Johnny – a man her own brother had warned her against – would have to lure out on the flimsy excuse that her now-dead husband (she had threatened to divorce) was sick. Driven at night, in a strange car, to an isolated yard, this paranoid lady with a lifelong fear of the dark would be led inside an odd little shed, illuminated by a single bulb, only to find... no Archie. Instead she would see three acid bottles, two steel drums (one empty, one full), a cracked monocle, a spatter of blood, a rubber apron, a set of gauntlets and - in Johnny’s hand - her dead husband’s revolver. “I went back to Brighton and brought up Mrs Henderson on the pretext that her husband was ill. I shot her in the storeroom, put her in another tank and disposed of her with acid”. But was it really that simple? (BANG / SLUMP / FIZZ). Well, yes, it was. And although it irked Johnny a tad to fritter-away his busy social schedule to do a double-murder, it was (at best) only a bit of a bother and soon enough, with the dirty deed done, Archie & Rosalie Henderson would vanish completely. In his diary, Johnny marked the moment “A is for Archie and the sign of the cross. R is for Rose, I didn’t deal with her until just before midnight”. And yet, so trivial were their deaths, had it not been for that note, he’d have forgotten - “yes, I suppose it must have been on the 12th when I got rid of them”. The killing-spree of John George Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers was complete. As expected, his fourth murder was perfect, his fifth was easy-peasy and with the Police unaware that anyone was missing, the rest would be textbook… but once again, having overlooked yet another small and seemingly insignificant detail, something would go horribly wrong. (Interstitial*) The Henderson’s were gone, and bit by bit, as Johnny picked it apart, so were their assets. (Haigh) “In the case of Dr Henderson I removed his gold cigarette case and pocket watch, and from his wife, her wedding and engagement ring”. Before their bodies were reduced to a dark smouldering goo, Johnny pawned-off a diamond and sapphire ring, a gold watch, a gold chain, a set of gold studs, a Pewter tea set and a silver cigarette case to Horace Bull, a jeweller in Horsham for £292. Johnny gave a false name and address, and all of the pieces were either sold-on, broken-up or smelted down. Having sidled-up in a red Lagonda which burst with boxes, golf bags and suitcases all monogrammed with a large flashy ‘H’, Johnny stashed the property of “two old pals who had gone to South Africa” into the garage of Thomas Davies - some of which, “at their request”, he would dip-into and flog off. Being post-war - with money tight, essentials rationed and the black market a bit of a grey area - the average bod didn’t give two hoots where a case full of hooky goods came from, so with a nod, a wink and no questions asked - unaware that they were destroying evidence - Thomas bought some golf clubs and glassware; Leonard & Gladys Bevan had five pairs of ladies shoes and a lamb’s wool coat; and Barbara Stephens (Allan’s daughter and Johnny’s sort-of girlfriend) got first dibs on a green linen dress, a mustard coloured blouse and a nearly-new bathing suit. And yes, some of it may have been a little scorched, but even Johnny’s overcoat had acid burns on the cuffs, so beggars can’t be choosers. Bits and bobs he stored in his garage to sell later; a metal filing cabinet, two office chairs and an electric heater, but all the best stuff he kept for himself at the Onslow Court Hotel. Of course, it wasn’t weird at-all that he wore dead man’s suits, shirts, ties, cuffs, belts and collars; that he proudly pranced about his bedroom (all peacock-like) in the deceased’s silk robe and slippers, or that Johnny played at being doctor by coveting a few odd objects from Archie’s life; like his hip flask, briefcase, stethoscope, kidney bowls, a brass thermometer, an inkstand and two metal plates marked ‘Archibald Henderson’? No, this wasn’t strange at all, as with the couple now dead and gone, all of this stuff… was his stuff. Okay, maybe Johnny was a tad careless to sell-off his victim’s stuff, to dress in his victim’s clothes, to drive his victim’s car, to take his victim’s dog and to sign his victim’s name on his victim’s cheques at his victim’s bank, but (as before) having laid a cunning subterfuge, Johnny had covered his tracks. One hour after her murder, having adopted a high-pitched voice, Johnny called the Metropole Hotel, and pretending to be Rosalie he stated the couple had (Haigh/Rose) “unexpectedly been called away”, and (concerned for his wellbeing) asked the night porter to feed and walk Pat, their elderly Red Setter. Four days later, clutching a seemingly legal-looking letter supposedly signed by the Henderson’s which gave this random stranger total authority to do as he pleased: (Haigh) “I paid their hotel bill, collected their dog and took their luggage to Dawes Road”. With their account settled in full, the animal gone, the room vacated and the luggage collected, the hotel had no reason to be concerned. Being fond of Pat, Johnny cared for the old dog in his hotel room, where he was loved, brushed and fed on meat rations he’d bought having queued-up for hours at the butchers, he even took the almost-blind dog to an eye-specialist, but with pets being against the hotel’s rules, Pat was put into kennels. With the old ploy practically fool-proof, as before (Haigh) “I kept the relatives quiet by sending letters purporting to come from the Henderson’s to Rosalie’s brother Arnold and Archie’s sister Ethel”. Having stolen their passports, identity cards, driving licences and marriage certificate “I acquired the forged deeds of transfer for 16 Dawes Road” - this time with no spelling mistakes or dodgy signatures -and, once again, he collected the rent, in person, having introduced himself as the tenant’s new landlord. Oh yes, the murders were a doddle, the subterfuge would be a done deal and soon it was time for tea, toast and scrambled egg. I mean it had all worked before so why change a winning formula? Besides, with Ethel busy moving house in Jersey and having swallowed a semi believable story that Archie & Rosalie were moving to Durban, she wouldn’t be aware that anything was amiss until a year later. As for the disposal? Well, Johnny had got the knack now, and as the fifth person he’d liquefied in less than five years, it was all very simple, so in just forty-eight hours The Henderson’s went guts to gloop. Step One: (Bang); a single shot, at close range, blasted in the back of the head, Rosalie dropped like a sack of spuds; the walls muffled the noise, the dark disguised the killing, the fence hid the storeroom. Step Two: (Slide); stripped of stuff (rings, ID, keys, cash), bent double, hog-tied with twine as the limbs were still floppy, she’s slid inside a 40 gallon drum and (as a slight eight-stoner) easily propped upright. Note to self (Phone): Find a phone-box, call Metropole Hotel (Haigh/Rose) “hullo, Rosalie here, could you take Pat for a walkies”, then lock the door, lights off, home for snooze and a hearty breakfast. Step Three: (Pump): Apron on, gauntlets on, gas-mask on, with the carboys still and bucket be damned, stirrup-pump thirty gallons of sulphuric until the drums are four fifths full, windows open and lid on. Step Four: (Fizz): first ten mins, acid turns black as hair, eyes and flesh are stripped; next thirty mins, acid boils as it reacts with the blood and fat; drum rattles a bit, then settles, quick stir with a rod, then a cuppa tea. After three hours; muscles, tendons and cartilage are gone, but the skeleton remains. Second note to self: (Phone) drums are three foot high, the McSwan’s and Rosalie were five foot eight max, but Archie was six foot, so with his left foot sticking out and not dissolved (Haigh) “Hello, White & Son? I’d like to order a forth carboy of acid”, an extra cost, a slight delay, but job done, no biggie. Step Five: (Drum) two days later, with the drums cooled, the gloop tepid and a greasy yellow sludge on top with a black smoky soup beneath, give it a quick stir, check there’s no big bits but a few small fragments is fine. Sadly with no drain at Leopold Road, both drums are dragged into the yard, the goo is tipped amongst the trash and car oil, and soaked into ground, it’s not ideal but the gloop is gone. And as always, a quick clean-up followed, nothing major; apron up, gauntlets away, gas-mask stowed, carboys collected, ID and victim’s stuff stashed, gun and gas-mask back to hotel room, give the drums a rinse out with acid (as fat tends to cling to the sides), dump both in the yard, and after a quick wipe-down with a rag (as blood’s a dead giveaway), return the storeroom keys back to Edward. Easy-peasy. A thorough murder investigation headed-up by Detective Chief Inspector Guy Mahon and Home Office Pathologist Dr Keith Simpson wouldn’t be conducted until more than one year later, after Johnny’s confession, but by then, very little of The McSwan’s or The Henderson’s would be found. In the last half a decade, the basement at 79 Gloucester Road had changed hands several times, so in terms of cast-iron proof, it was useless. Any personal items belonging to these five victims could have been legally acquired at any time (which Johnny certainly had the paperwork to prove) and as a full year had passed, any evidence relating to the Henderson’s at Leopold Road was purely circumstantial. There would be no witnesses; nobody on Leopold Road saw, heard or smelled anything strange coming from this engineer’s workshop. Between Brighton and Crawley, nobody spotted Johnny with either of the Henderson’s that day. There would be no ballistics; no bullets, no holes, no casings and although a firearms specialist recreated the shot, shielded by brick walls, it sounded like a muffled pop. Being a dirty oily storeroom, the investigators were unable to pull a single fingerprint from any surface. His clean-up was slap-dash, but using a wet rag he wiped away any trace of the Henderson’s blood. Of their personal possessions; the cracked monocle was proven to be Archie’s, as were the gas-mask, the revolver and the hat-box marked with a monogrammed ‘H’, as well as his and his wife’s ID’s, licences, marriage certificate and passports, all which were legally acquired and none of which was a body. And although forensics found a beech-wood rod with one end disintegrated, two rusted steel drums, a stained apron and gauntlets, and a series of zig-zag marks in the soil as two heavy drums were dragged from the storeroom to an ominous pool of yellowy-green grease, this suggested was that something had been dissolved in acid, but that wasn’t unusual for an inventor who experimented in plastics. The Police would find no hard evidence that the Henderson’s were at 2 Leopold Road, and as you can’t fingerprint sludge, Johnny was right, (Haigh) “Corpus Delicti - with no body, there can be no crime”. Only having overlooked another small detail, once again, the killer risked capture. (Interstitial*) (Haigh) “I found The Henderson’s interesting and amusing, we went about a good deal together, they talked a lot about themselves, and from many conversations I learned a great deal about them”. To Johnny, whereas Archie was the prize, Rosalie was a mere formality who could be rubbed-out as easily as he could erase her name, and as he listened to her life-story, some bits he stored, but most bits he binned. Rosalie Mercy Burlin, known as Rose, was born on 11th September 1907, as the eldest of two siblings, with a younger brother Arnold - (Haigh: “urgh, boring-boring-boring”) – to Edith, an English housewife - (Haigh: “argh, snooze”) - and Adolph, a naturalised German dentist – (Haigh: “Ah! A dentist? Bingo!”). Described as a neurotic paranoid hypochondriac, Rose’s nervousness began when her uncaring nanny thought the best way to keep a chatty child quiet was to tell the tot terrifying tales and lock her in a pitch black room; a childhood trauma which resulted in years of therapy, terror and tranquilisers - (Haigh: “a dull little detail there, but… like Archie’s bad back and poor eyesight… possibly useful?”). Educated at Pendleton High School, Rose trained as a typist at the Pittman College and began a short career as a secretary - (Haigh/flips pages: “secretary, secretary, short-hand typist, modelled once but mostly unemployed. Oh, so she’s got no money, her dad’s a financial risk, her mum’s just a wife and her brother runs a crappy seaside hotel in Blackpool, so basically, they’re all worth nothing. Damn it!” (Haigh) “Right! Rosalie; thirty-seven years old, five foot seven and eight stone; slim, weak, wet; with drawn on eye brows, chronic nerves and a painted smile. In short; sad, false and pointless. Typical! In 1931 she married Rudolph Erren – ah, an engineer, an inventor and founder of the Erren Motor Company. Hmm. Oh, start of the war, he’s suspected of being a Nazi; arrested, interred, divorced and later deported back to Germany. Shame. Meanwhile…” (Haigh) “Rudolph & Rosalie live opposite Archie & Dorothy, which we know. Archie & Rosalie have an affair, which we know. Rosalie taunts Dorothy with this knowledge, which we didn’t know, nasty bitch. Rosalie shacks-up with Archie (an abusive alcoholic womaniser). Archie gets Rosalie pregnant? Ah-ha! Illegally aborts the baby? Ah-ha! In Dorothy’s sitting-room? Ah-ha! Dorothy leaves Archie and three days later she dies suspiciously. Hmm, I may have to consider blackmail? This follows eight years of lies, drink, affairs, blah-blah-blah, and haemorrhaging cash (oh I know that feeling) The Henderson’s sell-off their very expensive and tastefully decorated twenty-bedroomed house at 22 Ladbroke Square in the exclusive suburb of Holland Park, which is where they met me… and – even though, for any pedants, this last bit was touch of dramatic licence rather than an actual quote - the rest we know”. Only he didn’t. Johnny only cared about one thing, money. As for people? His only concern was what they were worth so anyone whose money wasn’t worth stealing he disregarded as irrelevant; a mistake he had made before with The McSwan’s and now with Rose Henderson. Every rose has its thorn… …and his name was Arnold Burlin. On 3rd September 1947, being broke and keen to weasel his way into the life of a man he thought was a wealthy mark, (Haigh) “I met the Henderson’s by answering an advertisement offering for sale of 22 Ladbroke Square”; a house they had purchased for £4600, would sell for £8700 (to cover their debts), and yet, much to the befuddlement of Rose’s younger brother, Johnny declared “that’s too cheap, but if you accept £10,500, that’s a deal”. As a no-nonsense Blackpool hotelier, attuned to spotting an unsavoury-sort too poor to stump-up a pound to pay his bill, Arnold later said of Johnny “of the scores of stupid people I’ve met, I’ve just been introduced to the greatest of them all”, later advising Rosalie “when you meet a man who talks like that, you should run for your life”, and although she kept a bit of a distance, Archie did not. The last time Arnold saw his sister was on 1st February 1948 in their flat above the ‘Doll’s Hospital’ toy-shop at 16 Dawes Road, as being asset-rich but cash-poor, having loaned the Henderson’s £160 to furnish it, Archie repaid it, that day, by cheque. The last time Arnold spoke to his sister, was by phone, a few days before her death; she was unwell, bed-bound but fine. (BANG/SLUMP/FIZZ). (Haigh) “I kept the relatives quiet by sending letters purporting to come from the Henderson’s”. And a skilled forger who over the previous months had mastered their handwriting, spelling, style and tone, once again, his cunning subterfuge began. On Saturday 14th February, on headed paper swiped from the Metropole Hotel, Johnny penned a letter from Archie to Daisy Rowntree, manageress of the ‘Doll’s Hospital’ toy-shop. It read; (Haigh/Archie) “Dear Daisy. Mrs Henderson & I are going away for two or three months, first to Scotland and later abroad. In my absence Mr Haigh will look after my affairs. I am closing the shop. Mr Haigh will keep you for a few days to enable him to take stock. Mrs Henderson and I send you kind regards and hope to see you again when we return. Yours sincerely Archibald Henderson”. Received on Tuesday 17th, Daisy was shocked, as in short she’d been sacked; no thank you, no warning, no reason and no goodbye, just gone - an uncharacteristically callous dismissal from a man he liked. That same day, Arnold dropped-in, as the cheque had bounced. Shocked at Daisy’s distress and the fact that his sister’s affairs were being handled by a stranger, he told Daisy to (Arnold) “do nothing till I speak to them”. (Phone) Unable to contact the Henderson’s, he traced Johnny to the Onslow Court Hotel; (Arnold) “Here, Haigh, what’s all this about then?” Caught off-guard by the nosey Northern blighter, Johnny reassured this nobody he had nothing to be concerned about, the Henderson’s merely owed him a rather sizable debt, and he had all the paperwork to prove it, don’t you know? But being immune to Johnny’s charms and seeing the little louse as “a bit too smooth”, Arnold was suspicious. It was odd, usually Johnny’s letters worked like a treat, but then again, the reclusive McSwan’s weren’t like the recalcitrant Arnold Burlin, so if he wanted proof, he would get proof, in the form of a forged contract from Archie to Johnny, backdated eight days before their deaths and signed by the dead. For Johnny, this wasn’t an issue, but a golden opportunity to fleece the deceased. (Typewriter / Archie / Haigh) “To J G Haigh. I acknowledge receipt of two thousand five hundred pounds on part loan for three months. For repayment I hereby assign to you: the stock at 16 Dawes Road, a Standard Saloon, a blue lacquered bedroom suite and other items on inventory to come. This leaves a value of £1500 outstanding and should I require the loan after the 3rd May 1948, I will assign to you the freehold of 16 Dawes Road. Signed Archibald Henderson, witnessed by Rose Henderson”. Would Arnold buy it? He didn’t know. So… …as a second layer of lies to bed-in his bullshit, Johnny penned a letter from Rose to himself dotting it with hints as to why they unexpectedly departed, written on Metropole Hotel note-paper with Brighton crossed-out and Edinburgh scrawled beneath, which is quicker than travelling to Scotland. It read (Rose/Haigh): “Dear Mr Haigh. To let you know that we are alright, as you must be wondering when you were going to hear from us. Archie is quite different now and (you won’t believe it) he is laying off the bottle! He has at last come to his senses and realises that I could not carry on as we were doing. We are going to Aberdeen tomorrow for a day or two and shall be calling at my brother Arnold’s on our way back. Archie won’t get in touch with him because he sent him a bad cheque. It was good of you to help him, I do appreciate it and hope you are having luck with the stock at Dawes Road. I shall look forward to seeing you again before we go to South Africa. I hope Pat is not giving you any trouble. Please give my kind regards to Daisy. Yours sincerely. R Henderson”. Not subtle, but effective. Sadly, as Pat’s blindness was incurable, being placed in kennels, although he was genuinely concerned about the dog’s welfare, it resulted in the only two occasions when anyone recalled Johnny becoming upset; once when Pat was put to sleep, and later when a tabloid falsely accused him of animal cruelty. But Johnny’s soft and sensitive side didn’t cut the mustard with Arnold… On Monday 23rd February 1948, determined to get to the bottom of this, Arnold asked to meet Johnny at 16 Dawes Road, in the sitting-room of which he spotted the Henderson’s suitcases and passports. Eek! Fearing his ruse had been rumbled, Johnny spun a semi-believable story about drink and debts, locked the flat, and unsure if he had pacified Arnold, he fired off another letter, this time from Rose. Typed, signed and dated Friday 27th February with a Birmingham postmark, it read (Haigh/Rose) “Mr dear Arnold. We’ve never had such a long silence, you must wonder what happened? Unfortunately Archie found out that I was leaving him. We had a perfect bust-up at Brighton and he threatened to commit suicide if I left him…” followed by some family bumph and bluster… “I thought we might be along to see you this weekend but we must keep on the move for a little while yet, probably three more weeks. We are keeping away from Archie’s usual haunts. Archie is as good as gold and is very seldom drinking. I only hope Johnny Haigh is doing alright because he has been a brick to me during the last few months. Hope you are all well. Don’t worry. Give my love to mummy. Rose”. Did it work? Did it not work? He didn’t know. So, to be sure, he fired off a few postcards. 27th February, Birmingham, Archie to Arnold and Johnny – “Am doing very well, that is Rose is, and we shall be returning at the end of March. Archie”, which made sense, as Archie was a man of few words. 5th March, Rugby postmark, Rose to Daisy – “Hope you are alright and getting on well with Mr Haigh. We are very well and having a busy time. See you at the end of March. Kind regards. Rose”. 5th March, Rugby, Rose to Arnold – “Hope my letter put your mind at rest. I expect the details would amuse you at least. Arch is still very good and the Brighton episode was a blessing in disguise. Love to Mumsy and all. Shall see you on our way back. Rose”. Only this time, Johnny had misspelled Mumsie. And again, 5th March, Rugby, in a postcard written by Johnny, as Rose, and sent to himself - “To let you know we are still well and very busy. Hope you are alright. Kind regards. Rose”. And although Arnold couldn’t help but be drawn-in by the catalogue of convincing correspondence, he couldn’t explain the passports, the suitcases and why Rose’s personal address-book was found in Johnny’s car. On Friday 19th March, having not spoken to Rose in person for more than a month, Arnold contacted a friend at the Stockport Police who agreed to look into the possible disappearance of the Hendersons. Alarmed at this news, and panicked, the very next day, Arnold received a telegram, it simply read “Going to Scotland tonight, contact you Tuesday or Wednesday. Rose”. It was short, but as a stalling tactic, it gave Johnny time, as two days later, three letters arrived at three different addresses. (Typing) 21st March, Glasgow, Rose to Arnold and Mumsie, this time spelled correctly. (Rose/Haigh) “This is very confidential so you’ll have to discuss its main points with Mr Haigh and McNab Taylor (a firm of solicitors Johnny had appointed). I write to you in a hurry because our boat to South Africa leaves on Tuesday…”, and in a fifteen page letter in which he hammered home the need for everyone to lie low and stay schtum, the key points were there; “write to us courtesy of the General Post Office in Durban until we know our address”, letters of which would sit for month gathering dust in a box, “Archie has made over the property to Haigh and sent it to McNab Taylor for completion”, meaning Johnny owned 16 Dawes Road, and all the while reassuring what remained of Rose’s family, “I hope you won’t feel too sore but it’s the only thing we could do if Archie wasn’t to go bankrupt. I don’t want you to worry about me. With my very warmest love to you all. Yours. Rose”. That day, a second letter was sent to McNab Taylor, the solicitors and the third was sent from Rose to himself, thanking Johnny (Rose) “I’m glad to say we’ve done it. With much thanks to your assistance which other friends seemed to lack the courage to do. Yours very sincerely Rose Henderson”. And before Arnold could even reply… …legally, the Henderson’s assets were stripped, Johnny was back in the black, Arnold was none the wiser and there was nothing anyone could do, or prove. And as Arnold’s detective friend in the Stockport Police found nothing suspicious, the Henderson’s were never reported missing. Everyone who knew them believed they had started a new life nine thousand miles away… when in truth, they were both little more than a black sludge slowly sinking into the dirty soil at Leopold Road. (End) To little Johnny Haigh, murder had become routine. Yes, it sometimes got quite exciting when things went awry, as sticky beaks were stuck where they didn’t belong and the simple transfer of funds between two accounts were sullied by that tiresome annoyance – people. But people are people. Once again, Johnny had failed to learn from his fatal mistakes, as having overlooked a seemingly small detail, something had gone horribly wrong… but with a simple snip, the Rose was clipped, its thorn was blunted and – whether by pluck or luck – Johnny had pulled-off another perfect murder. To pacify Arnold was simple, as his trouble began with a bounced cheque by Archie, Johnny just wrote him a new one and once the cash had cleared, Arnold returned to Blackpool and Johnny never saw him again. And soon enough, although puzzling, Archibald & Rosalie Henderson would be forgotten. It took a single second to kill the Henderson’s, just two days to dissolve their corpses and after only eight weeks, Johnny had full control of their entire estate; from their home, shop and stock, to their shares, savings and their life insurance. Ah yes, the good life had returned; and as a respected middle-class gentleman with a business to run, good suits to wear and three sports cars to drive, Johnny’s toughest decision was between taking tea or tiffin with the rich widows at the Onslow Court Hotel. Annoyingly, as a notoriously irrational and irresponsible gambler, of the £20,000 Archie had been left in his dead wife’s will, having sold 22 Ladbroke Square to cover his mounting debts, although Johnny had spent literally months perfectly preparing the untimely demise of his old pals – The Henderson, their deaths only netted him a piffling £7700. I know! I mean, yes, that’s just over quarter of a million pounds today, but it wasn’t the three quarter of a million pounds he’d been hoping for, but hey-ho. Still, with more than enough money to last a lifetime, this time at least, the killing spree of John George Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers would finally come to an end… …or would it? (Interstitial*) OUTRO: Friends. Thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. That was the penulti8mate part of Sulphuric; the true story of John George Haigh, with the final part of six continuing next week. A big thank you to those lovely people who very kindly showered me with gifts on my previous Murder Mile Walk, it was unexpected and lovely; they were Emma Thorpe, Jonny Rex, Jessica from Asian Madness Podcast and the lady with the large black suitcase who very kindly gave me some yummy spiced Christmas biscuits, it happened so fast I never got your name, but thank you. And also a hello to Hamish, my boat neighbour and listener to Murder Mile. Ssshh! Only you know what my boat looks like, so that’ll have to remain our little secret. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER *** The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, therefore mistakes will be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken. It is not a full representation of the case, the people or the investigation in its entirety, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity and drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, therefore it will contain a certain level of bias to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER ***

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards 2018", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

EPISODE EIGHTY:

On the morning of Thursday 12th February 1948, two years after the triple murder of the McSwan family, with John George Haigh having blossomed into a respected businessman with enough money to last a lifetime and had no plans to kill ever again, he lured his new pal - a wealthy man of dubious morals Archie Henderson - to his workshop at 2 Leopold Road, where he murdered him and dissolved his body in acid. But why did Johnny return to a life of crime?

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

I've added the location of 22 Ladbroke Square with a blue dot, where The Henderson's first met John George Haigh. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, Paddington or the Reg Christie locations, you access them by clicking here.

Left to right: Archibald Henderson (Captain), 22 Ladbroke Square (home where the Henderson's first met John George Haigh), Rosalie Henderson and 14 Dawes Road, the "Doll's Hospital" toy shop with their flat above where Johnny stole the revolver (used to kill Archie) and the gas mask.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This series was researched using the original declassified police files held at the National Archives, the Metropolitan Archives, the Wellcome Collection, the Crime Museum, etc. MUSIC:

SOUNDS:

TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: PART FOUR OF SULPHURIC.