|

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018 and iTunes Top 50. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within one square mile of the West End.

EPISODE FORTY-EIGHT

Episode Forty-Eight: On Saturday 7th October 1944, 32 year old East London orphan Muriel Eady vanished from Ladbroke Grove in West London, one year after 21 year old Ruth Fuerst, but with this being war-time, it was believed that she was just one of thousands of unidentified bodies and body-parts littered across the city’s bomb-craters, but she was the second confirmed victim of the infamous British serial killer John Reginald Halliday Christie. This is part two of the full, true and untold story of The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations (and I don't want to be billed £300 for copyright infringement again), to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

Ep49 – The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place – Part Two - Muriel Amelia Eady

Trust - a firmly-held belief that a person is reliable, truthful and honest. It can’t be faked, traded or bought, it can only be earned. And unlike any greeting, gossip or pleasantry, trust takes time, patience and tests, before we let anyone into our confidence and open up to our inner-most secrets. Trust is reserved solely for friends, family and (in rare exceptions) strangers; like firemen, policemen, doctors, nurses, soldiers and security. But without a bloodline, a bond or a uniform, trust requires a kind face, a caring voice and a calm demeanour. In 1942, The Blackout Ripper struck, killing four women having gained their trust; he was tall, charming and handsome, with a crisp RAF uniform, bright blue eyes and an easy smile. Where-as Reg Christie was not; he was short, scrawny, balding and bespectacled, a strange man in a crumpled old suit; with an odd little whisper, false teeth that slipped and (no longer being a Special Constable) no uniform. But what he lacked physically, he made up with mentally, meaning that (for a whole decade) his killing spree would go undetected, all because he was kind, caring and – worst of all – patient. In August 1943, Reg Christie murdered 21 year old Ruth Furest in a fit of spontaneous lust. One year on, with his urge unsated and his carnal desire swelling, having learned from his mistakes, this murder would be planned to perfection. And with a fresh victim in his sights, he needed to gain her trust. Some of what follows is based on the killer’s own memories and perspective; so what part of this story is true… is up to you. My name is Michael. I am your tour-guide. This is Murder Mile. And I present to you; part two of the full, true and untold story of The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place. SCRIPT: Today, I’m standing by the A40 on Western Avenue in Perivale; a heavily industrialised part of West London, far from the seediness of Soho, but in an area absolutely vital to our story. As a chaotic dual-carriageway connecting the capital city to the Welsh coastal town of Fishguard, you may think you don’t know the A40, but with a small stretch of it also called Oxford Street, the A40 passes-by the Denmark Place fire, Freddie Mills suicide, Jacque Tratsart’s homicide, Mary Pickwoad’s abortion, Abd al-Naif’s assassination, several locations of The Blackout Ripper, and as it exits Edgware Road to become the Paddington fly-over, the A40 overlooks what remains of 10 Rillington Place. Situated 9.3 miles west of Soho, as one of London’s busiest roads, Western Avenue is noisy, dirty and chaotic; as with the deafening thunder of trains, the choking fumes of trucks and ear-splitting scream as jumbo-jets roar out of Heathrow, amidst a thick smog of swirling dust, nasally it’s a very confusing place, as enveloped by factories whose chimneys burp out the sweet scent of biscuits, curry and beer (mmm) often it’s interspersed by a caustic cloud of chemicals, burnt rubber and sewage (not mmm). Although I’m standing directly opposite the infamous Hoover Building; a stunning grade-two art-deco factory built in stark white-concrete with shimmering green glass, the exact location of the place I’m looking for is unknown, and what was left, has been entirely demolished. Now occupied by the Greenford Premier Inn - a budget hotel where tired salesmen forgo the arduous two-hour commute (to the wife and kids) and instead, sink a few suds, scoff a steak, pay for a porn film by mistake and mysteriously book a double-room for themselves and their “daughter” who visits her “daddy” for just “58 minutes” (I’m guessing) – but originally, sat on this site was Ultra Electrics Ltd; a radio manufacturer whose war-work was so secretive, that to confuse any Nazi saboteurs, they incorrectly listed their address as being in both Acton and Park Royal, almost three miles east. And yet, in the summer of 1944, it was here, that a shy, bright but lonely lady called Murial Eady was lured into the confidence of a delivery driver who had secrets of his own. (Interstitial). Muriel Amelia Eady was born on 14th October 1912 in Canning Town, East London; a dark, squalid and impoverished district on the north-side bank of the River Thames; with a skyline chockful of belching chimneys, the sooty air thick with an acrid soupy smog, the murky brown water fizzing with effluent, and surrounded by the endless cacophony of docks, cranes and iron-works. And being one year into the stark austerity of the First World War; with food rationed, fuel in short supply and the ominous low-drone as German Zeppelins crept silently amongst the clouds, stealthfully dumping bouncing balls of burning magnesium which shattered, sparked and set the city aflame, in what would become the original (and long-forgotten) London Blitz - this was no place to raise a child. But to Muriel this was home. Muriel was born at 20 Baron Road; in one of thousands of identical Victorian terraced houses built to serve the dock workers in the 1850’s, and later demolished in the slum clearance. Although tiny, it was home to their mother Fanny Louisa Eady, five year old Reginald, three year old Ernest and Muriel. To Muriel and her siblings, Fanny was everything; a doting single-mother who struggled alone on a single income with three small children. And although she was still married to William Eady - a sailor in the Merchant Navy who rarely (if reluctantly) returned home and was a father in name only - in the 1911 census, it rightfully lists Fanny as “head of the house”. And although one of her babies was always sick, as raised amongst the sooty choking gloom of Canning Town, Muriel suffered with asthma, adenoids and catarrh which would plague her for life (SNIFF), being blessed with such a wonderful mother; Reginald, Ernest and Muriel thrived and survived. And then, in February 1918, as one of deadliest pandemics swept across the globe killing close to one hundred million people, having been struck down with deadly influenza, a virus for which there was no treatment or cure, Fanny Louisa Eady died in Poplar Hospital. Muriel was just six years old. Being distraught, what she wanted was a hug, what she needed was her mum, but what she got was William Eady; an unsmiling uncaring stranger, who – being gruff, rough and grumpy – only cared for the sea, and seeing these kids as nothing but a burden, he abandoned them. Three grieving children; all alone, scared and cruelly orphaned were placed into care at the Hutton Poplars Residential Home for Destitute Children in Brentwood, where they would remain for most of their childhood. And as a shy girl, struggling for an ounce of love in a stern Victorian orphanage full of seven hundred screaming kids and crying babies, with no mother to guide her and fearing any father-figure, in the six years she remained at Hutton Hall - feeling rejected, abandoned and alone - Muriel became secretive and retreated into isolation, trusting no-one but herself. (Christie’s whisper) “I knew I wanted her, the Eady woman, but she were different from the others, you know, quiet-like, so it had to be a really clever murder, much cleverer than the first”. (End) As a young girl, Muriel cut quite a sad figure as her flat-feet scraped along the care-home’s stone floor; her shoulders slumped, her back hunched and the dark brown curls of her hair hiding her heartbroken eyes. And as the days dragged on, for fear of being abandoned again, this became her shield. Muriel was a ragged little mess dressed in oversized clothes, whose chest wheezed, whose nose sniffed (SNIFF) and who rarely made a sound except to emit a timid nasal squeak. After close to six years in care (being made to feel less like an abandoned child and more like a burden on the state) aged eleven, her father’s sister-in-law, Ethel Souhami, asked to look after Mariel. This should have been her chance to bloom, to blossom, to put the past of her fractured family behind her and start her life afresh, by playing with some new-found pals and living in a sweet semi-detached house on a peaceful tree-lined street at 48 Creswick Road in Acton, West London. But although she liked to be called “Aunt Ethel”, she had no plans to become Muriel’s new mum. As a fastidiously neat, supremely strict and mealy-mouthed French widow, being partially disabled, Ethel struggled to run a lodging house, which was home to five regular residents from the local Police station, all of whom needed meals cooked, beds made and uniforms ironed. Ethel needed a shy silent servant, who would do as she was told; with her head down, mouth closed and would sleep in a box-room under the stairs; working every hour of every day, for no money, no rest and no thanks. Her servant was Muriel and this became her life for the next fifteen years. By 1939, Muriel was twenty-seven years old; she was unmarried, uneducated and friendless, with no money, no social life, no love-life and (being unwilling to trust the local doctor) her catarrh began to plague her with headaches, Muriel had very little experience in life… and yet, it was almost over. That April, whether as a blessing or a curse, Aunt Ethel died. And with no next of kin; the house was sold, the lodgers moved out and Muriel was left penniless, homeless and (once again) abandoned. But finally being free, for the first time in a very long while, Muriel started to live. A few months later, she was working as a laundry assistant at Pembroke College in the historic city of Cambridge, and although war had been declared and Europe was in chaos, for once, Muriel had money, freedom and hope, and living in a shared lodging, she began to come out of her shell. By 1940, with the Blitz still a few months away, Muriel had moved back to London and was lodging at 12 Roskell Road in Putney; a nice little terraced house in a neat little street, owned by Martha Elizabeth Hooper, her mother’s sister. But unlike dreaded old Aunt Ethel, Auntie Martha was a sweet lady with a warm smile, a big heart and all-embracing hugs, who – best of all - reminded Muriel of her mum. By 1943, being bored of a life in domestic service, with millions of men being posted overseas to fight for King and Country, new roles had opened up for women, so being eager to ‘do her bit’, Muriel began a career as an assembler at the Integral Auxiliary Equipment Company on Power Road in Chiswick, where she learned how to build hydraulic pumps for aircraft and met her new best friend – Pat. By 1944, relishing her independence, Muriel’s confidence began to blossom, as guided by Pat, the two pals (described as being like “two peas in a pod”) became regulars at the Half Moon Public House on Lower Richmond Road, the amusement hall by Putney Bridge and a dance-hall called the Black & White Milk Bar on Putney High Street, and as her social-life bloomed, Muriel had begun to date. Eager to expand her horizons, Pat put her pal forward for a plum job. And being a “skilled assembler” who was regarded as “essential labour” making vital components for the war-effort, on 20th April 1944 Muriel Eady began work at a recently built factory on Western Road, it was called Ultra Electrics. It was a good job, at a nice firm, for a steady wage and a bright future. And with her confidence at an all-time high, Muriel had begun to make a few new friends… one of whom, was a softly spoken former Special Constable who (in the months ahead) would meticulously plan her death. (Interstitial) (Christie’s whisper) “I were medically-trained, you know, in the Army, so my knowledge of medicine made it possible for me to talk convincingly about sickness. She believed I could cure her”. With Ultra Electrics producing over a thousand radio sets a day for civilian and military service, as well as radio equipment for one of Britain’s best war-time multi-strike aircraft - the de Havilland Mosquito - work was busy but rewarding. In staggered shifts of fifteen minutes, a multitude of machinists, assemblers, checkers, packers and office staff descended on the factory’s canteen, mingling by the tea-urn, scrimmaging for Chelsea buns and jostling for space on the benches. Muriel was one face in a sea of fifteen hundred; all identically dressed in oily overalls, black boots and hair-nets, and yet it was here, over a nice warm cuppa, that she got chatting to a lorry driver from the despatch department called John Reginald Halliday Christie. (Christie’s whisper) “I prefer it if you call me Reg”. The cruelty of her lost childhood had taught Muriel never to trust anyone, so experience should have warned her to steer clear of Christie, but as a blossoming wallflower with a bright future ahead, as they chatted, she began to enjoy his company. To Muriel, Reg was a happily married man (Christie) “twenty four years to be precise”, a former Special Constable (“commended twice”) and a decorated war-hero (“awarded the British War & Victory Medal”). With a badly crumpled suit, thick-lensed spectacles and false teeth which slipped when he smiled, he didn’t look sinister, he looked silly. So why she liked him? We may never know. But being just slightly older than Muriel and named Reginald, perhaps this harmless man reminded the lost child within her of happier times with her own big brother? And with that, he began to gain her trust. (Christie’s whisper) “I knew I wanted her, the Eady woman, but she were different from the others, you know, quiet-like, so it had to be a really clever murder, much cleverer than the first”. (End) Christie would later claim that the murder of Ruth Fuerst was unplanned, a spontaneous act of lust on a desperate and (possibly) pregnant woman, he had lured to his home with a gift of ten shillings. Where-as Muriel was independent, self-sufficient and guarded; with a good job, a solid wage, a stable home, a busy social life, a best-friend called Pat and (it is believed) a boyfriend called Ernest. Five years prior, Muriel’s life was a mess, but now, she didn’t need anything from anyone. Christie hadn’t killed in a year and with the Police suspecting that Ruth was simply one of thousands of unidentified bodies or body-parts which littered the city’s bomb-craters having been blasted to bits by any number of aerial bombardments, the evidence of his evil crime lay undisturbed in a shallow grave in his back-garden. But seeing Muriel, knowing Muriel and liking Muriel, as those same dark urges swelled, he knew that he wanted her, and that she would be next, but without a way in, he would need to be patient. Over the next few months, he played the part of a trusted friend, inviting Muriel and her boyfriend to his home, to meet his wife, to chat over tea and cake, and even make up a foursome to the flicks. It made a nice change for Reg & Ethel to have company, as although they were a nice enough couple, they were rarely close, choosing to shower any affection on their dog Judy, rather than each other. And as pleasant as the charade was, it solved one big problem, only to open up another; Muriel liked Reg, she trusted him and she was comfortable in his home… but now, he needed to get her alone. In September 1944, tragedy struck, when a high-explosive bomb fell on a packed air-raid shelter killing everyone inside, one of whom was Pat. To Christie, the cruel death of Muriel’s best pal should have been a blessing as being so bereft, most people would seek out the sympathetic ear of a trusted friend? But as familiar feelings of abandonment rose once again, being inconsolable, even by her boyfriend, Muriel retreated into solitude and Christie was at a loss… (SNIFF) …but then again, tears can have terrible side-effects on a person plagued with catarrh. (Christie’s whisper) “…it had to be a really clever murder, much cleverer than the first. It were my wide knowledge of medicine which made it possible for me to talk convincingly about sickness and disease, and she readily believed I could cure her”. (End) And as promised, a few days later, for the first time in decades, Muriel Eady wouldn’t feel pain… any more. On Saturday 7th October 1944, after a tiring shift at Ultra Electrics, made all the more gruelling as her throbbing head and painful sinuses had plagued her with weeks of fitful sleeps; Muriel dressed in a navy blue blouse, black shoes, a black artificial silk dress with a pink collar and a camel-coloured cloche coat. At four pm, she left her Auntie Martha’s home at 12 Roskell Road in Putney, saying “I shan’t be late”. She didn’t say where she was going or who she was meeting, she was never seen alive again. At a little after five pm, having exited Ladbroke Grove tube station, guided by a small torch along the pitch-black street, Muriel took her usual route to Reg’s; the clomp of her tired feet accompanied by her chorus of coughs, wheezes and sneezes, as she passed David Griffin’s Refreshment Room, headed east along Lancaster Road, up St Mark’s Road and went left into the dark dead-end of Rillington Place. The street was pitch-black, as with each resident sticking to the strict war-time rules of the blackout; every light was off, every curtain was closed and every door was shut, and with any sound muffled by the distant thud of bombs and tube trains which thundered by, the street was empty and eerily silent. Knocking at number ten, as the black door crept open a crack, Muriel was greeted by the slobbering drool, whimper and occasional widdle of Reg’s brown mongrel – Judy; but sadly, although Reg was here, being up in Halifax to stay with her brother, tonight they wouldn’t have the company of Ethel. So, lighting the gas-light and taking her coat, with a fresh pot of tea brewing on the hob, Reg led Muriel along the thin drab hallway, passed the front-room (with its loose creaky floorboards), the bedroom (with its once strangely stained sheets), and into the cosy little kitchen, barely yards from the little back garden, where Ruth’s decomposing corpse lay undiscovered, and – soon – so would Muriel’s. Over a cuppa, the two friends chatted, with Reg perched on a small round stool in front of the alcove, as Muriel reclined in the wooden deck-chair; a grey blanket covering the five lengths of rope with a spare draped over the back, his plan to repair it. And although Reg had been off-sick with fibrositis affecting his back and his bronchitis having flared-up, his priority was to solve Muriel’s catarrh. It was well-known that Reg had a wide knowledge of medicine; as a Special Constable “commended twice” he had trained in First Aid and was awarded two certificates which proudly hung on his wall; as a student doctor, he had read a-good many medical books before his training “was cruelly cut-short by The Great War”; and as a war-hero, “whilst serving in the Nottingham & Derbyshire Signal Corp” he was disabled in a mustard gas attack which left him with a voice little more than a whisper, Muriel knew Reg was experienced, trusted and (best of all) knowledgeable. So as Muriel coughed, wheezed and sneezed, looking a sorry-sight who sighed with lack of sleep, Reg sympathised. As a frequent sufferer of catarrh himself, he knew that the menthol mist expectorant she’d been prescribed was “next to useless”, he knew could cure her, and Muriel knew it too. With a reassuring smile, Reg gently placed into her hands a square glass jar, six inches deep and wide, which his wife had used a few times prior to pickle fruit. Inside (instead of the potted plums) sloshed a white liquid which smelled strongly of the reassuring whiff of Friar’s Menthol Balsam. And with two crude holes drilled into the metal lid; into the right hole ran a two-metre length of rubber hose, starting in the depths of the white bubbling liquid and disappearing off towards the curtain by the slightly open kitchen window, where-as into the left hole was the short stubby end of a rubber hose, through which Muriel would inhale. Yes, it looked a little bit silly and home-made, but Reg reassured her, it would do the trick. And so, as Muriel leaned over the square glass jar, having placed a large scarf over her head to fully ensure she absorbed its medicinal goodness, Muriel breathed deeply, inhaling the minty bubbling vapours. Within a minute, with her sinuses clearing and her pain disappearing, Muriel felt different. But the long rubber hose wasn’t there as a steady supply of fresh air from the open window, used to purify this “special compound”. Instead, Reg had connected the hose to the gas-pipe. And with the strong eggy smell of coal gas disguised by the overpowering eucalyptus of the Friar’s Balsam, as Muriel breathed deeper, her lungs slowly filled full of carbon monoxide, an invisible deadly gas commonly known as the ‘silent killer’. Christie wasn’t a heavy man, muscular or strong, so even the act of overpowering a small weak girl like Ruth Fuerst had been a struggle. And yet, with no force or assault, just a little bit of trust and a lot of patience, he had willingly rendered Muriel unconscious. And as she lay there, slumped in his deck-chair, silent, still and passive, Reg strangled her with a length of rope. (Christie’s whisper) “Once again, I experienced that quiet peaceful thrill. I had no regrets”. (End) Only this time, his sordid deed wouldn’t be disturbed by an urgent telegram, as Ethel would be away for weeks; he wouldn’t be interrupted by Mr Kitchener, the elderly deaf tenant in the flat above; and he wouldn’t receive a call from any worried friends or concerned relatives, as (of those she hadn’t lost contact with) no-one knew she was here… but Reg. And as he dragged Muriel’s lifeless corpse along the communal hallway and into the bedroom, over the next few hours, he would savour every moment of his long-awaited prize; as he fondled her slowly cooling breasts, caressed the curves of her stiffening body and kissed her protruding purple tongue which jutted from her ruptured bloated face, as having wanted her for months, now her body was his. And unlike in his joyless, sexless marriage to a frumpy baggy hag, for once, Reg had no problem getting or maintaining an erection, as his lustful urges descended into necrophilia. (bed springs) The next night, her body was buried in the back garden of 10 Rillington Place, alongside Ruth Fuerst, with any identification destroyed and all possessions sold. And although a missing persons’ report was issued, hospital admissions were checked and her details were tallied with any lists of unidentified body-parts found during the aerial bombardments, Muriel became one of thousands of missing people who disappeared during war-time. And having been cruelly abandoned by fate and a father (in name only), through strive and struggle, Muriel had finally begun to live the good life that she truly deserved, but having dropped her guard to a trusted friend – simply so he could cure her catarrh – the life of Muriel Amelia Eady was ended. (Christie’s whisper) “I knew I wanted her, the Eady woman, but she were different from the others, you know, quiet-like, so it had to be a really clever murder, much cleverer than the first”. (End) OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. If you enjoyed parts one and two, part three of The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place continues next Thursday. And if you’re a murky miler, stay tuned for some mindless waffle after the break, but before that, here’s my recommended podcasts of the week; which are Nordic True-Crime and Hoosier Homicide. (PLAY PROMO) And don’t forget, if you’re looking for a special Christmas or birthday gift, check out the Murder Mile merchandise shop, as we have exclusive Murder Mile mugs, badges, thank you cards and bespoke gifts, but also a threadless store full of t-shirts, bags, wallets, literally everything. You could also treat a loved one, to a subscription to Murder Mile’s patreon account, and receive each episode days before everyone else. Links are in the show-notes. Murder Mile was researched, written and performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER *** The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, therefore mistakes will be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken. It is not a full representation of the case, the people or the investigation in its entirety, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity and drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, therefore it will contain a certain level of bias to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER ***

Credits: The Murder Mile true-crime podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed by various artists, as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0. A list of tracks used and the links are listed on the relevant transcript blog here.

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British podcast Awards 2018", and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 75 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018 and iTunes Top 50. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within one square mile of the West End.

EPISODE FORTY-EIGHT

Episode Forty-Eight: On Tuesday 24th August 1943, 21 year old Austrian refugee Ruth Fuerst vanished from Ladbroke Grove in West London. Having been missing for almost a decade, it was believed that she was just one of thousands of unidentified bodies and body-parts littered across the city’s bomb-craters, but – in truth – Ruth Fuerst was the first confirmed victim of the infamous British serial killer John Reginald Halliday Christie. This is part one of the full, true and untold story of The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations (and I don't want to be billed £300 for copyright infringement again), to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

Ep48 - The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place – Part One (Ruth Margarete Christina Fuerst)

Memories are subjective. We all see the same sights, we all hear the same sounds and we all smell the same smells, but (burdened by a limited capacity) our minds only remember the smallest of fragments, all of which are distorted by time, bias, emotion and trauma. The simplest of details may imperceptibly change; colours, shapes, sizes, names, dates, times and even locations, to the point where two people, sitting side-by-side, in the same room, at the same time, may see the same event in a radically different way as their brains edit that brief moment to suit their own perspective. Unconsciously we all do it, and yet, we all believe that our memories are real. In 1943, just two miles west and less than one year after horror of The Blackout Ripper, a second serial sexual sadist stalked the bomb-damaged streets of London. Strangely, they both wore uniforms, they both struck during the blackout and they both appeared as kind, pleasant and caring. But unlike The Blackout Ripper – whose insatiable lust for sex and death left four women dead and two lucky to be alive – this serial-killer was older, wiser and calmer. Seen as an upstanding pillar of society, a happily married man and a decorated war-hero who lived locally at 10 Rillington Place, although he was known as Mr Christie, to those he liked he preferred they call him Reg. And yet, in a reign of terror which would last (not a few days but) a whole decade; eight women would disappear, one man would be executed and no-one would suspect him. You may think you know this story, as many variations of it have been told, but with much of the evidence destroyed, there is no definitive account of what happened. Some of what follows is based on the killer’s own memories and perspective; so what part of this story is true… is up to you. My name is Michael. I am your tour-guide. This is Murder Mile. And I present to you; part one of the full, true and untold story of The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place. SCRIPT: Today, I’m standing at 110a Ladbroke Grove, W10, at the farthest fringes of London’s West End; three miles west of Soho, one mile north of Hyde Park and within spitting distance of Portabello Road, Notting Hill and that infamous blue front-door adorned by Hugh Grant but owned by the film’s writer, who subsequently (following the film’s success) sold the house for oodles of cash - clever man. Now called The Flowered Corner, 110a Ladbroke Grove is a four-storey brown-brick Victorian terraced house nestled on the north-east corner of the crossroads of Lancaster Road and Ladbroke Grove; with the Kensington Park Hotel and North Kensington Library opposite, just as it was during war-time. With three flats above, the ground-floor is a floristry-shop; a single bright spot on a dirty dusty street, where the sweet smell of nectar is strangled by the greasy stench of chicken shops, the soothing colours of tulips are smothered by the choking fumes of trucks, buses and tube-trains, and the harmonious tranquillity of fresh pansies was once (as witness by myself) sullied - without no hint of irony – by a rather displeased youth cussing from a beaten-up banger; with his music blaring, no lights on and no windscreen, who was smoking a spliff, wearing a “f**k da Police” t-shirt and bemoaning two straight-faced coppers by complaining “why you police always hassling me?” Back in the 1940s, 110a Ladbroke Grove was known as David Griffin's Refreshment Room; a simple café serving standard British staples like tea, coffee, toast and fry-ups for a reasonable price in a poverty-stricken area. Inside (away from the bombs, the death and the debris) it was safe, welcoming and warm. And yet, it was here, on 21st August 1943, that a 21 year old girl called Ruth Fuerst, who had already escaped her certain death… would meet her new murderer. (Interstitial) Ruth Margarete Christina Fuerst was born on 2nd August 1922, the second of three children to Ludwig, an Austrian landscape painter and Friederike, a Jewish housewife, with an older brother Gottfried and younger brother Gabriel. Raised in the middle-class affluence of Zurich, Switzerland’s largest city, Ruth’s upbringing was peaceful, happy and joyous; and being a well-educated girl from a very liberal and unpolitical family, she embraced her life, her rights and her freedom. Eager to become a nurse, although a little bit shy; Ruth was always studious, intelligent and patient. Having inherited her father’s slim awkward frame, being a few inches taller than most girls, she always stood out. And as a fastidiously neat girl, with pale (but easily flushed) skin, brown (but eternally sad) eyes and a neat bob of dark straight hair - a colouring passed down from her mother’s Hungarian ancestry - although Ruth looked typically Jewish, she wasn’t. Plagued with minor complaints from birth; like a hereditary blood disorder (which often left her weak), buckled knees (which kept her excluded from sports) and terrible teeth (which left her in chronic pain), as a beloved girl from a well-to-do family, able to afford doctors, medicine and – fortuitously – a metal crown fitted to her upper-right molar, life could have been a lot worse. In need of fresh air, good light and striking landscapes to paint, her father (Ludwig) moved the family to a spacious villa on the edge of a forest, at Waldandacht funfzehn, in the picturesque Austrian spa-town of Bad Voslau, famed for its lush vineyards and rolling hills, twenty-three miles south-west of his hometown of Vienna. Being surrounded by her family, Ruth was happy, safe and loved. And although this affluent and bustling market town was home to just over nine-thousand people, by the late 1930’s, many homes would become vacant, many people would vanish and - for the first time in its history – the population of Bad Voslau would rapidly shrink. On 15th September 1935, with the National Socialist German Worker’s Party having risen to power and its leader - Adolf Hitler – appointed as the country’s Chancellor, fuelled by rabid anti-Semitism, bigotry and a decree to “protect German blood and honour”, the Reichstag established the Nuremberg Laws. Its purpose; to create an Aryan state and to eradicate anyone who wasn’t a pure-blood, whether black, gay, Romany, disabled, or Jewish. The Nazis classified a Jew as anyone who practiced Judaism, identified as Jewish, had married a Jew, was dating a Jew, and – regardless of whether they were (and always had been) a practicing Roman Catholic, as many German Jews had been since in 19th century – if any person had a traceable Jewish ancestry, they were subject to the Nuremberg Laws and regarded as a ‘mischlinge’ (or half-blood). Born Friederike Altmann, with her mother being a Hungarian Jew, although Ruth was a devout Roman Catholic who was never without her silver crucifix, being classified as a ‘mischlinge’, aged fourteen, Ruth was forced to leave Volkschule Bad Voslau on 4th July 1936, ending her dreams and her education. For the next two years, under Nazi rule, with all five members of the Fuerst family being ‘mischlinges’, they were all denied any rights, freedoms and being treated as an ‘untermensch’ (German for sub-human), Ruth and her family were forced to undertake menial and demeaning jobs. One of which included scrubbing the road surfaces with acid, which left Ruth’s palms badly scarred forever. On 12th March 1938, as the Nazis annexed Austria, ‘Anschluss’ was enacted, therefore – by law - all Jewish owned properties were seized, all personal belongings were sold, and having been forcibly separated, the fate of the Fuerst family was unknown. Some hid, others fled and where-as the rest were rounded-up and transported to uncertain fates. For the first time ever, Ruth was alone, homeless and scared, she was just sixteen years old. From 1st October 1938, for eight months, Ruth hid in a basement room at nummer zwei Nestroyplatz in Nazi-controlled Vienna, never knowing if her family were alive or dead. With fate smiling upon her, aided by a Swedish Christian mission, Ruth was issued with a passport and on 8th June 1939, just three months before start of World War Two, and being hungry and exhausted, Ruth fled to England. And yet, having escaped the horrors of the Nazi regime; a life of poverty, persecution and her certain execution, it was here, in the safety of West London, that Ruth Fuerst would end up dead (Interstitial). (Christie’s whisper) “She were Austrian I believe, a nice girl, plain but sad-looking. I’d met her in the summer of 43, in a café in Ladbroke Grove. Got herself in a dreadful mess she had, awful, so I gave her a few shillings – you know - to help her along. That’s all. It seemed like the right thing to do”. (End) On 1st September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany; a brutal six-year conflict which left homes decimated, families displaced, countless casualties maimed, crippled and traumatised, and - by the end of it all - at least eleven million people would be dead. One of whom was Ruth. Having just turned seventeen, Ruth was still a child; an impressionable young girl from a foreign land, who was scared and lost in a big strange city, with a limited grasp of English, a patchy education, weak legs, bad blood and sore teeth, with no skills, no friends and no family. And although she was thankful to be safe - missing her mother’s hug and her father’s love – she was alive… but also so alone. The last four years of her life were solitary and chaotic, and as much as she strived, she struggled. Initially, she lived with her guarantor Miss Edith Bessie Willis, in a delightful white terraced cottage at 92 Oakwood Road in the very Jewish north-west London neighbourhood of Golder’s Green. But with Edith being a prim and proper lady, and Ruth being a distraught teenager with scars on her hands, an emptiness in her heart and unimaginable horrors still plaguing her mind, they never got on. Still seeking to fulfil her dreams, being “intelligent and alert”, Ruth enrolled as a student nurse at St Gabriel’s Home in the seaside town of Westgate-on-Sea, and upon graduation, with a bright career in her sights, Ruth found work at the Santa Claus Children’s Home in Highgate… and life had hope. And then, as an Austrian exile who had legally entered England, even though she was just a young girl, being unsure whether she was a Nazi sympathiser, Ruth’s newly adopted country had her transferred to the Hutchinson Internment Camp in Douglas; a cold, barren and inescapable prison on the remote Isle of Man in the middle of the Irish Sea; surrounded by bare walls, locked doors and barbed-wire. Sixth months later, having been deemed “not a threat” by the British Government, Ruth regained her freedom. But with her job gone, her reputation ruined and her life in tatters; with German bombers obliterating every city, Ruth was evacuated from London and (once again) uprooted to the windswept wilds of Elswick in Lancashire, where she knew no-one. And still, her life would only get worse. Half a year of enforced captivity had taken its toll; and where-as once this sweet, polite and joyous girl had been replaced by a fiery moody mess with tatty clothes, sullen eyes and unwashed skin; looking like a ragged orphan - which she knew she most likely was - Ruth had become trapped in a mental fog. With a doctor diagnosing her as “severely depressed”, although the capital wasn’t safe, for the sake of her mental wellbeing, Ruth moved back to familiarity of London. London was a city in ruins. After eight months of sustained aerial bombardment, as a wave-after-wave of bombers rained down death from the sky, the deep ominous drone of their engines untraceable amidst the thick clouds of black smoke. And although The Blitz was over, having failed to pummel the proud populous into submission, with the Luftwaffe being unrelenting, the bombings continued. An estimated forty-three thousand civilians would die during the air-raids, as with a daily risk of being killed by an incendiary bomb, a doodlebug or a V1 rocket, to many Londoners, death was a part of life. Houses would vanish overnight, sometimes terraces and even whole streets. And with its occupants being obliterated by blast-waves or incinerated by fire, the only evidence that a family ever existed, was when the Special Constables (a merge of my voice and Christie’s) “pulled bodies from the debris; sometimes alive, sometimes dead, sometimes whole, injured or disfigured, and yet sometimes all that was left was a foot, a hand or a head. Nasty business it was”. (Christie’s whisper) “But in war-time, it wasn’t unheard of for someone to simply vanish”. (End) Being eager to rebuild a small semblance of life and feeling like she was slowly becoming a Londoner, with the war being really just a bit of an inconvenience to her routine – as soot stained her skin, dust clogged her lungs and as she’d munch some bread, only to hear a crunch as she’d bit into grit – having endured rationing, blackouts and the limitations of her refugee status, Ruth ploughed on, hoping to truly make something of herself and (God rest them) her parents proud. In December 1941; whilst living in a small but pleasant lodging at 141 Elgin Crescent in Maida Vale, studying for her return to nursing and working as waitress at the exclusive May Fair Hotel in Stratton Street, W1, just shy of Piccadilly Circus; although she was a shy girl who struggled to make friends, Ruth met and fell in love with a Greek Cypriot waiter called Anastasio Isiedoran. A few months later; being rosier about the cheeks, fuller round the hips and with a noticeable bump, Ruth discovered that she was about to become a mum. And with the little miracle of a baby girl blossoming in her belly, having prayed nightly to the Lord and him (finally) hearing her cries, he blessed her with one more miracle; Friederike and Ludwig Fuerst - her mother and father - weren’t dead. Having fled the horrors of the Nazi regime and boarded a boat; her parents were alive, well and living in the safety of East 57th Street in New York City, where – they hoped – Ruth would join them. But being heavily pregnant, desperately broke and very recently single, in her state, Ruth knew that she couldn’t… (Christie’s whisper)…”and – as fate would have it - she wouldn’t”. As a young girl with weak legs, bad blood, poor teeth and frequent bouts of depression, life was hard. As an unskilled and partially-educated female in the nineteen-forties, life was harder. As a war-time refugee of Austrian-Jewish heritage living in London, life was even harder. But also being an unmarried expectant mother of no fixed abode; with no job, money or immediate family, life was impossible. So, on 9th October 1942, in the West End Lane ‘Home for Unmarried Mothers’ in Hampstead; being alone, scared and desperate, Ruth gave birth to a baby girl, who she named Christina… moments later, her baby was taken away. She never saw her again. From the end of 1942 to the middle 1943, having moved from job-to-job, lodging-to-lodging, leaving a trail of unpaid bills, as slowly she sunk back into depression, Ruth’s life returned to chaos. On 25th May 1943, Friederike received the last letter Ruth would ever write. Albeit brief (with all of the war-sensitive details deleted by national censor), in it, she stated she was working the night-shift in a local munitions factory, and reassured her mother that she was fine, well and she sent her love. On 29th June 1943, Ruth quit her job as a machinist at John Bolding & Sons of 56-58 Davies Street, W1, a munitions factory at the back of Bond Street station. And although she was always tired, tardy and sickly, barely working twenty hours of her forty hour week, her co-workers believed she was pregnant. On Saturday 21st August 1943, at a little after lunchtime, Ruth was seen by her landlady - Julie Teresa Walker – leaving her flat at 41 Oxford Gardens as she walked one road south towards Ladbroke Grove tube station wearing a distinctive fake leopard-skin coat. That was the last confirmed sighting of Ruth Fuerst. Believing she’d absconded without paying her rent, her landlady reported her missing ten days later. As one of many of missing refugees, her details appeared in the Police Gazette two weeks after that, but nobody searched for her. And as one of thousands of innocent civilians killed during the aerial bombardment, the mystery surrounding her death wouldn’t be investigated until a decade later. (Christie’s whisper) “She were Austrian I believe, a nice girl, plain but sad-looking… but in war-time, it wasn’t unheard of for someone to simply vanish”. (End) After this moment, only one person witnessed her alive; a Special Constable working out of the Harrow Road police station who’d been commended twice by the Police Commissioner and as a local man – who was moral, teetotal and charitable - was widely regarded as an upstanding pillar of society, a happily married man and a decorated war-hero. The Special Constable’s name was John Reginald Halliday Christie, known as Mr Christie, but (Christie’s whisper) “I prefer it if you call me Reg”. It was Saturday lunchtime. As per usual, although small and snug, David Griffin’s Refreshment Room at 110a Ladbroke Grove was busy, as throngs of famished regulars glugged tea, nibbled toast and tucked into hearty British fry-ups, which – like the walls – oozed with a thick slather of pig fat. In the corner, Ruth and Reg sat side-by-side, as they had done several times before. Ruth found it difficult to make friends, but with Reg being so approachable, kind and caring, even though he and his wife (Ethel) had no children of their own, the word which best described him was fatherly. As a slightly built man, twice her age but the same weight and height as Ruth, Reg seemed a harmless sort. And being almost totally bald (except for a thin crown of brown hair above his ears), wearing thick-lensed horn-rimmed spectacles (which magnified his soft brown eyes), a set of false teeth (which being too big sometimes slipped as he spoke) and talking in a barely audible whisper – having been injured in a mustard gas attack whilst bravely serving his country during The Great War – although he looked a little odd, she could see that Reg was a sweet and caring man who wouldn’t harm a fly. Ruth and Reg sat together, him having bought her a tea and toast, as he listened to her woes. His hand tenderly touching hers, but it wasn’t hard and coarse, but a little bit limp and damp. (Christie’s whisper) “Got herself in a dreadful mess she had, awful” (End). Being ten days away from failing to pay her rent, once again, Ruth risked eviction. Being unemployed, she couldn’t afford a check-up on her weak legs, her bad blood, her chronic teeth or the new baby which was (possibly) on the way. And as a deeply moral man who “never used prostitutes myself”, during war-time he’d often turn a blind-eye to good women who’d fallen on hard-times and struggled to make ends meet. (Christie’s whisper) “…so I gave her a few shillings – you know - to help her along. That’s all. It seemed like the right thing to do”. (End) Or so he said. And yet, the Police could find no-one in David Griffin’s Refreshment Room who remembers seeing either Reg or Ruth that day. Having visited his home twice before and kept this Special Constable company on his beat, on Tuesday 24th August 1943, Ruth entered Rillington Place; a grey featureless dead-end lined with ten three-storey Victorian terraced houses on both sides, with no trees, plants or front gardens, and – like it was cutting the street dead in its tracks - a ten-foot high brick wall behind which tube trains thundered by. Keen to collect those ten shillings, Ruth knocked on the black wooden door of 10 Rillington Place. First to greet her was Judy, Reg’s over-excitable brown mongrel who widdled a little when stroked, but once again, there was no sign of his wife Ethel, who was up north visiting her family in Halifax. The hallway was thin, drab and dark; to the left was a set of stairs which led up to other tenant’s flats, and to the right was the ground-floor flat which belonged to the Christie’s; with a front-room, a bedroom and a kitchen, with a neat little garden and a communal wash-house and lavatory outback. So with tea brewing on the hob, Reg ushered Ruth along the thin hallway into the kitchen. Oddly, none of the residents in Rillington Place remember seeing either Reg or Ruth that day. Having no central heating, limited electricity and illuminated by Victorian gas-lights which bathed the pokey kitchen in a flickering yellowy glow, as Reg perched awkwardly in front of the alcove on a small round stool, Ruth leaned back in his one good seat. By “good”, it was really just a wooden deck-chair draped in a grey blanket and held together by (what should have been) six lengths of rope, but as she sat there, supping a nice cuppa and getting toasty in front of the wood-burning range. Ruth was cosy. For a while they chatted, as the older man imparted his wisdom, knowledge and fatherly advice to the inexperienced girl, keen to help her out of her difficult situation; with her rent due, bad teeth and (possibly) another baby in her belly. But it was as she stared into his soft brown eyes; longing for love and missing a man’s touch, that – being overcome with lust – Ruth started to undress. (Christie’s whisper) “She were madly in love with me” (End). Christie was a happily married man, for twenty-three years, he didn’t do this sort of thing and was quite shy to boot, but as she slowly undid the buttons on her fake leopard-skin coat, revealing a young slim body with a full heaving bust, being a woman with strong sexual urges, Ruth led Reg into his bedroom. (Christie’s whisper) “She were completely naked, lying on my bed, wanting me to have intercourse with her” (End). And as much as Reg reminded her he was married (Christie’s whisper) “she wanted us three to team up, to go away somewhere together. I wouldn’t do that” (End). But not wishing to offend her, (Christie’s whisper) “I got on the bed and had sex with her”. Of the many statements he gave, all are inconsistent; sometimes he’d be pedantic about the smallest and most insignificant of details (“no it definitely wasn’t that”) and yet, he’d be impossibly vague about whole events (“I can’t be certain, it were a while ago, you know?”). But when asked where, when, how and why he murdered Ruth Fuerst, he would simply state (“I don’t recall”). Except to say: (Christie’s whisper) “it were while I was having intercourse with her, I strangled her with a piece of rope”. As the full weight of Reg’s naked spindly body bared-down upon her, his putty-white legs pressed tightly around her skinny thighs, trapping her legs; as Ruth’s arms flailed wildly - being gripped in panic, fear and unable to breath, let alone scream - the more her trembling hands grasped at the taut rope which slowly crushed her throat, the tighter he pulled it. As her soft youthful skin turned a mottled shade of puce as the blood vessels in her face swelled and ruptured. As the tightening ligature forced her tongue to jut-out of her mouth like it was trying to escape from her silently screaming face. As being in uncontrollable terror, her shaking body expelled its last splash of urine and faeces. And as the capillaries in the whites of her eyes began to burst so they appeared almost black, the last thing that Ruth saw - wasn’t the sweet smile of her baby daughter, the peaceful fields of her hometown of Bad Voslau, or Ludwig & Friederike Fuerst, her beloved parents – but the terrifying grimace of Reg Christie; the father-figure she liked, trusted and (he thought) loved, as in his hands he gripped both ends of the straining rope, until her life drained away. There she lay, dead. (Christie’s whisper) “She looked more beautiful in death than in life… I remember I gazed down at the still form of my first victim and experienced a strange peaceful thrill”. But his thrill was to be short-lived. (Loud knock at door) Receiving a telegram that his wife would be home that evening, Reg dragged the naked corpse from the bedroom, along the communal hallway and into his front room, and under a large rug, where (with a few floorboards loose after a plumber had repaired a leaky pipe) he hid Ruth’s body. Ethel arrived home that night and – with fresh sheets on the bed, her brother (Henry) fast asleep just a few feet away, Reg having burned the clothes in a dustbin and buried the body by the back-garden – she was none-the-wiser; of the sex, the death, the body, or her husband, the murderer. There were four other tenants at 10 Rillington Place that day, but none of them heard a sound. And although, John Reginald Halliday Christie made several vague statements; when asked in court “Mr Christie, was this the first person you had killed”? He would reply (Christie) “I think so, I don’t recall”. 21 year old Ruth Margarete Christina Fuerst was just a girl with weak legs, bad blood and painful teeth, who (somehow) had escaped persecution, anti-Semitism and her extermination in a concentration camp at the hand of the Nazis. She had endured hardship, poverty, hunger, bombings, imprisonment, abandonment and the loss of her family, her home, her baby and – finally - her life. But being listed only as missing, not dead and certainly not murdered, Ruth Fuerst would become just one of thousands of innocent civilians believed to have been killed in the war-time bombing raids. (Christie’s whisper) “She were Austrian I believe, a nice girl, plain but sad-looking… but in war-time, it wasn’t unheard of for someone to simply vanish”. (End) OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. If you enjoyed part one, part two of The Other Side of 10 Rillington Place continues next Thursday. And if you’re a murky miler, stay tuned for more goodies after the break, but before that, here’s my recommended podcasts of the week; which are Unresolved and Dark Histories. (PLAY PROMO) A huge thank you goes out to my new Patreon supporters, who are literally saving my life by financially keeping Murder Mile afloat with their generous donations, which I definitely don’t spend on cake. This week’s heroes are Alex Stone and Harriet Oliver. May your world be full of Belgian buns, battenbergs and fondant fancies. For me? That’s as good as heaven. Murder Mile was researched, written and performed by myself, with a special voice cameo by Police Constable Arsenal Guinness and with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well.

Credits: The Murder Mile true-crime podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed by various artists, as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0. A list of tracks used and the links are listed on the relevant transcript blog here.

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British podcast Awards 2018", and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 75 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018 and iTunes Top 50. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within one square mile of the West End.

EPISODE FORTY-SIX

Episode Forty-Six: On Sunday 25th July 1965, in Goslett Yard in Soho; world champion light-heavyweight boxer, film star and club-owner Freddie Mills was found dead, shot in the head. But was it a suicide, or murder? This is part one of a two-part episode.

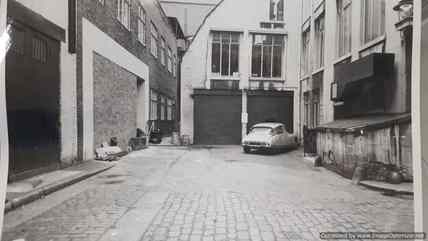

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations (and I don't want to be billed £300 for copyright infringement again), to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

46 - Who Killed Freddie Mills? – Part 1 - The Theories