|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND ELEVEN:

On Wednesday 28th December 1836 at roughly 2pm, off Pineapple Place in Maida Vale, the dismembered torso of an unidentified lady was discovered hidden behind a paving stone. With no arms, no legs and no head, her identity was impossible to determine, but the investigation and discovery of subsequent body parts unearthed one of the most brutal murders in British history.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of Pineapple Place, near Pineapple Gate where the torso of Hannah Brown was found is located where the red triangle is. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

Here's two little videos of the locations for Ep111: The Scattered Remains of Hannah Brown. To the left is the footage by the Maida Hill tunnel where Pineapple Place once stood and where the torso of Hannah Brown was found and on the right is Stepney Lock where her head was found.

This video is a link to youtube, so it won't eat up your data. I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Top to bottom and left to right: the rough location of Pineapple Place where the torso of Hannah Brown was found, Stepney Lock where her head was found, The Angel pub where the pre-wedding drinks were to take place, St Giles In The Fields Church where the wedding was to take place, an example of Hannah's home and the villas near Pineapple Place.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0. SOURCES: This case was researched using the original court documents from the Old Bailey, as well as many other sources. MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about Hannah Brown, a hard-working sweet-natured widow in her twilight years of her life who was looking to settle down, set-up shop and move to America with her loving husband-to-be. Every part of her dream came true, only what she found wasn’t happiness, but death. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 111: The Scattered Remains of Hannah Brown. Today I’m standing by the Maida Hill tunnel, just off Edgware Road, W2; four blocks north of the seedy hotel where Agnes Mary Walsh met her demise at the hands of the Sad Faced Killer, three blocks north of the odd suicide pact of Lieutenant Colonel Felic Sterbe, one street north-east of the floating suitcase found to have been stuffed with the suffocated corpse of Marta Ligman, and one street west of the unsolved and deeply troubling death of Amala De Vere Whelan - coming soon to Murder Mile. Situated within tooting distance of the dingy squalor of Paddington station, running parallel with the busy roar of Edgware Road and skirting the eastern edge of the last stretch of the Grand Union Canal is a series of long elegant avenues comprising of opulent white-stone villas for the seriously wealthy. As a former hunting ground known as Tyburnia, around the 1830’s when construction began, although it was only one and a half miles from Marble Arch and the Tyburn Gallows (which marked the entrance to the city), this part of Maida Vale was still regarded as countryside. One of the few thoroughfares of which was Edgware Road, and a few yards from this spot stood a toll-booth called Pineapple Gate. Of course - except for the avenues, the canal and the tunnel - very little still exists of the woodland, the toll-booth or the exact location at Canterbury Villas where this first grisly discovery took place. This is a gentle canal-side walk, where couples drained of conversation beyond the occasional grunt toss scraps of focaccia to the disapproving ducks, sip a glass of house white as the trucks thunder by, drool over the houses no-one could never hope to buy (if they actually pay their taxes) and dream of a better life in a bigger house… only stuck with the same old misery-guts. But then again, that is love. To many, love is for life. But to some, love is brief, convenient and a necessary evil to a quick solution. By Christmas 1836, fifty-year-old widow Hannah Brown had found happiness, love and (after years of hard-work and heart-ache) she was about to fulfil the dreams which she truly deserved. She felt alive, whole and complete, and yet – with her life cruelly cut-short - her arms, legs and head were missing. As it was here, on Wednesday 28th December 1836, just off Pineapple Place, that the first piece of Hannah Brown was found, and unveiled one of the most brutal murders in British history (interstitial) There was never a lovelier lady than that of Hannah Brown, as said every single one of her friends and neighbours, and although - in death - pleasantries are readily spoken, in Hannah’s case this was true. Hannah Brown was born Hannah Gay in the spring of 1776. Raised in the rural peace of the market town of Wymondham (in Norfolk), it was a place famed for brush-making. Coming from an aspirational lower middle-class family, Hannah was the second eldest child to a school master and a seamstress, who blessed their children – Mary, Hannah, Sarah, Rebecca and William – with a solid education, the skills to survive life and – more importantly – a level of politeness, decency and a strong work ethic. Being a real mix of both parents, Hannah was a strong stout woman who stood five-foot eight inches tall; with a long pale face, short thick teeth and brown hair down to her waist, with a high-chest, strong limbs and large hands. She was gentile, polite and elegant, but with a man’s physical strength. Described as friendly and warm, being blessed with so many faithful friends who would remain by her side through thick and thin, Hannah always had a song in her heart, a spring in her step and - no matter what, being so strong-willed - she would be prepared for everything that life would throw at her. By the turn of the 1800’s, Hannah was married; she was in love, happy and although accepting of the cruel fact that she could never bear children – she had a loving husband and a happy future ahead. But barely a few years later, Hannah was alone, childless and a widow, aged just twenty-three. By the 1810’s, Hannah had remarried and – once more - he was a good man who loved her dearly, but bad luck would strike again, and by the time she was in her mid-thirties, she had been widowed twice. As before, her friends and family rallied round, and with her grief dampened by a £400 inheritance which would keep this smart frugal lady safe and secure for a good long while, she didn’t need to remarry, but knowing that she loved to be loved, she worried that her love life was forever doomed. Having buried her second husband, shortly afterwards her brother-in-law was tragically killed leaving his pregnant wife a widow, who (unable to cope) was committed to an asylum. Hannah had no experience as a parent, but being a devoted god-mother, her warmth and compassion came naturally, she raised Mary-Ann as her own and often referred to this young sweet girl as “my daughter”. Mary-Ann would flourish and thrive as a hatmaker in Yarmouth, and it was all down to Hannah. By her forties, having moved to London’s West End and being an independent woman, Hannah earned her income as housekeeper to Mr Perrin, a hatter and Mr Oliver, an anchor-maker, all who hailed her as an asset. But keen to become her own boss, Hannah purchased a brand-new mangle off a carpenter called Mr Ward on nearby Chenies Street and became a washer woman. A physically demanding job which took skill and strength, but it wasn’t just to earn an income, it was to get her nearer her goal. In the parishes of Soho and Fitzrovia, Hannah was well-known, well-loved and easy to spot by her distinctive look; even if age had added a few wrinkles, a salt & pepper hue to her long hair and (in an accident with a fellow maid) had left a tear in the lobe of her left ear when an earring was ripped out. Elegantly dressed in a black silk cloak, a hand-woven shawl and a long black boa, she didn’t dress like a typical washer-woman, but again, she didn’t dress like someone pretending to be who she wasn’t. She was a decent, kind and staunchly sober woman, who worked incredibly hard to save every penny so she could fulfil her dream of buying a little shop of her own to sell fruits and pastries. By the winter of 1836, having started with a series of tragedies, the life of fifty-year-old Hannah Brown was looking rather rosy. She was happy, healthy and having fallen in love with a young widower - who loved her without question, he had asked her to marry him on Christmas Day and the two planned to emigrate to his farmstead in Canada - this is where she would spend the rest of her life… …only, when the world was celebrating Christmas, Hannah was being hacked to bits. Wednesday 28th December 1836 was a bitterly cold day. The wind was bitingly crisp, the canal was solid with ice and a thick layer of snow speckled the frozen ground. So cold was the earth that the workmen in Tyburnia had to wait to lay the pathways till the midday sun had softened the soil. At a little after 2pm, by the toll booth at Pineapple Gate, a builder called Robert Bond was returning to work when he spotted a four-foot long by three-foot wide paving slab propped against the wall of Canterbury Villas. It had been there for exactly four days, only now, it was hiding a large hessian sack. With frosted breath, as Robert heaved the brown coarsely-woven bag (which was as big and bulky as a small sack of coal), a slight tearing ripped at its sticky base as the leaking red liquid from within had frozen the sack to the cold-stone floor, leaving a vivid pool which was unmistakably blood. Alerting a policeman, PC Samuel Peglar arrived at the scene at 2:10pm, and when he held the lip of the sack, unwound its string cord (held in place by several crudely poked eyelets) and as the wide mouth of the sack gaped open, he gasped, as inside he witnessed the aftermath of an act of pure evil. Pale, naked and partially frozen, it was unmistakably a woman’s body, only with no arms, no legs and no head, it was just a torso. Being large framed, loose-skinned and high-breasted, her age was hard to fathom but early fifties seemed about right. With no birth-marks, her identity was impossible to tell. And missing two-thirds of her body, her cause of death was unknown. But whoever had hacked her to pieces had done so crudely (by ripping jagged tears through her thighs, arms and neck), but as the old rusty blade snagged and stalled half-way through - with brute force – each bone was pressed and bent till it snapped like twigs, leaving five jagged sticks poking out of the tatty stumps of her corpse. Requisitioning a barrow, the body was carted to the Paddington Police station on Hermitage Street (where it was preserved in vinegar) along with the hessian sack and the wood shavings at its base, but as no-one had been reported missing, the unidentified torso at Pineapple Gate was a mystery. In the months leading up to Christmas 1836, Hannah Brown’s life was good, in fact it was very good. Blessed with powerful arms, large hands and a solid work ethic, Hannah was a savvy woman who knew how to run a business well. With a new mangle, a warm fire and constant pots of boiling water on the stove, from the ground-floor at 45 Union Street in Fitzrovia, she worked in the front parlour, lived in the back, and although frugal, she was always kind and elegant, with her sights on a little pastry shop. With her parents dead, her sisters back in Norfolk and her god-daughter all grown-up, Hannah’s only family was her little brother William – who worked as a broker to Mrs Blanchard at 10 Goodge Street – and although they lived just one street apart – for whatever reason – they rarely spoke. And yet, as a truly lovely lady, Hannah was never short of old friends, new pals… and now, a male admirer. On an unspecified date in October 1836, while her mangle was being repaired by the carpenter Mr Ward on nearby Chenies Street and she was ordering a hessian sack of wood shavings to stoke her fire, it was there that she first set eyes on a very dashing gentleman called James Greenacre. Being a charming forty-two-year-old businessman with sorrowful eyes, a distinguished nose and a kind smile, whose curly brown hair and tatty side-burns were in dire need of a lady’s finesse, although they looked an odd fit – as he was a few inches shorter, a good deal thinner and eight years younger than Hannah – the couple were instantly smitten, having found their soul-mate with a lot in common. Equally being as unlucky in love, where-as Hannah had grieved by the graves of two husbands, living a short but harder life, James had lost three wives and had buried four of his seven children. And just like Hannah, although money could never replace a loved-one, he was financially secure having bought several houses in Camberwell (South London) and a one-thousand-acre farm off Canada’s Hudson Bay. Neither of them needed to remarry, but finding a kinship together, they both loved to be loved. Near the end of November 1836, James Greenacre proposed to Hannah Brown and she accepted. As devout Catholics, they had their wedding banns published by the minister of St Giles-in-the-Fields church on the 27th November, 4th December and 11th December and planning a little libation with a few friends next door at The Angel public house, they would be married at St Giles on Christmas Day. It was the epitome of a whirlwind romance. As a delightful couple, united in grief, who’d found love later in life and chose to be wed surrounded by a handful of Hannah’s dearest friends, as under a twinkling blanket of snow, Mr & Mrs Greenacre would emerge to jubilant bells and Christmas hymns. So smitten was Hannah, that although her plan was to sell-off her mangle, pack-up her clothes and wisely invest her inheritance in a little pastry shop in Fitzrovia, now she had a new dream. To pack-up, to marry, to move to Canada with her beloved husband James and to live the life that this wonderful woman truly deserved. She had no debts, no children and no responsibility. There was no real reason for Hannah to remain in England, so why not leave the smoggy drizzle behind and finally be happy? On Wednesday 21st December, four days before her nuptials, Hannah visited her brother William to inform him of her plans to emigrate, but – for whatever reason – he wasn’t invited to the wedding. On Thursday 22nd December, Hannah introduced James to her best friends Mr & Mrs Davis over a light supper in the Davis’s home at 45 Bartholomew Close in Smithfield. The conversation was cordial, the couple sat hand-in hand on the sofa and the Davis’ were ecstatic at the news that (with no parents of her own) Hannah wanted Mr Davis to give her away and Mrs Davis to be her bridesmaid. Both were delighted and honoured, if a little tearful at the thought of losing contact with their good friend, but James assured them that they would always welcome, at any time, to stay with them in Hudson Bay. And with that, although Hannah was a sober woman who never drank, instead she raised a goblet of water as the foursome of friends toasted the glorious wedding and bright future of Hannah Brown and her new beau. At 10pm they left, smiling, happy and walking arm-in-arm towards Newgate Prison. On the Christmas Eve of 1836, with the ground freshly sprinkled with a smattering of crisp snow, the festival smell of mulled wine and roasted chestnuts teasing every sniffly nose, and the joyous hum as carols were carried on the misty air, Hannah had finished packing-up her life at 45 Union Street. Her mangle was gifted to an old friend, her furniture was sold, the keys were returned, the rent was paid, her customers were thanked and her two rooms was left clean and ready for the next tenant. At 12pm, Hannah called on Catherine Glass, a friend and washer-woman who lived on Windmill Street to drop off an overnight bag and her wedding dress, so she could spend (as tradition decrees) her last night of freedom away from her husband-to-be. Hannah’s mood was bright, happy and beaming. At 3pm, wearing her black silk cloak, black boa and distinctive white shawl, as well as two elegant pearl drop earrings worn a little higher owing to the old tear in her left ear lobe, James and the coachman loaded Hannah’s three trunks into a horse-drawn carriage, and she left Union Street forever. By the next morning, at St Giles, Hannah was due to be married to the man that she loved … …but instead, her cold dead corpse had been crudely dismembered. So, what went wrong? James Greenacre was a lover and a liar. As a serial widower with three dead wives, all of whom he had met, hastily married and were all older and wealthier than himself, each one (whether by disease, fever or accident) had died young and left him as the sole beneficiary of their estates. And where-as Hannah had frugally saved the nest-egg which she had been bequeathed, James liked to spend. He bought a pub in Woolwich, a house in West Ham, a terrace in Camberwell, and (supposedly) a large farm in Hudson Bay, although no-one ever saw it. Prone to dodgy deals, often dabbling in untaxed tea, he had fled to America with a wife and four children, but by August 1836, only he returned to London. On an unspecified date two months later, James overheard a carpenter called Mr Ward chatting to a lovely but lonely lady who planned to purchase a little pastry shop with her £400 widow’s inheritance. James was instantly smitten with Hannah, and where-as she loved to be loved, all he loved was money. Marriage was the fastest route to legally acquire it. And to him, it didn’t matter that he wasn’t single. Four years earlier, whilst married to his third wife, as a serial philanderer, James also had a thirty-five-year-old mistress called Sarah Gale, together they had a son and they planned to elope to Canada. He needed money, Hannah’s money and marriage was the key… only something went horribly wrong. Late on Christmas Eve, as Mr & Mrs Davis picked-up a cut of mutton for the post-wedding roast, they bumped into James on Tottenham Court Road. He was agitated, flushed and barked “the wedding’s off”, rambling about how Hannah was “debt-ridden”, “morally-loose” and a “drunk”, as he barged by the aghast couple with a few borrowed tools under his arm, all tied-up in a brown hessian sack. His accusations were untrue, they knew that, but without Hannah here, how could they prove it? Six hours earlier everything had started so well, as James loaded onto a horse-drawn carriage the three heavy trunks full of her worldly possessions – such as some silks, pottery and trinkets, all of which would fetch a pretty price, as well as a pair of pearl earrings, a gold pocket-watch and details of her inheritance – as they trotted out of Union Street for the very last time, with James lovingly wrapping a warm shawl around her shoulders, to shield his cash-cow from the cold, as the couple headed south. Over the next hour, as the carriage clip-clopped over the River Thames, they kissed and cuddled as James regaled Hannah with the false hopes of what their new life together would be. All of it was true – the home, the marriage, the ship to Canada – only the woman he wanted by his side was his mistress. At 5pm, the carriage pulled into Carpenter’s Place in Camberwell; a tightly-packed terrace of slightly dilapidated houses with broken bricks, shattered tiles and cracked windows. As landlord, James owned them all, but being in arrears and ready to default, he had no plans to repair them, or even to stay. As he dragged the trunk’s dead-weight into the dark gloom of house number six, happy that none of the neighbours had seen them, James closed the door and shuttered the windows to hide his crime. Only, this wasn’t a murder, but adultery. James was a coward, plain-and-simple, who was no better at brutality than he was as a businessman. After the marriage, he wouldn’t kill her, he would fleece her and flee on a fast ship with his mistress Sarah and their son, leaving Hannah broke, alone and tearful. That was James’ plan… or so he would claim. Only Hannah didn’t know that, and neither did Sarah. Keen to spend Christmas Eve with the man they loved, that evening, the two women met for the very first time. They argued, they cried and - according to James – being a bit drunk, Hannah swung in her chair, fell backwards, hit her head on the fireplace and - out of blind panic - he disposed of her body. Of course, being a liar, her autopsy would tell a different story. Being seated at the time of the attack, with a cup of tea in her belly and no defensive wounds, Hannah was struck from behind with a heavy blunt object. With a force so hard she headbutted the table, it snapped her nose, split her skull and detached her right eye from the socket, so the ruptured eyeball dangled down the pale skin of her bleeding cheek. Conscious but dazed, as she steadied herself to sit upright, she saw two sights - her bloodied lap and James with a log – as across her swollen lumpen face, he struck again, fracturing both sides of her jaw, as she slumped hard onto the cold stone floor. And as this grieving widow, loyal friend and kindly god mother lay in a contorted heap, with her dreams now as shattered as the bones in her face, James slit her throat and stood as she rasped her last breath. A short while later, having stashed a few rusty tools in a hessian sack from the shop of Mr Ward the mangle-maker, as he barked to Mr & Mrs Davis “the wedding’s off”, Hannah Brown was already dead. Across the snowy Christmas night, as joyous carols drifted in the foggy air, behind the dark shutters of 6 Carpenter’s Place, a young boy endlessly wailed at the sights he was seeing. As sat atop of a table, with a fresh corpse below his knees, as the old rusty saw he had stolen was barely sharp enough to rip the muscle and sinew, but was too blunt to sever through her neck, perching the corpse’s head over the edge, his father - James – pressed and bent with all of his force, until the fifth vertebrae went snap. Crudely, her limbs were severed likewise, as (quickly recovering from the shock of such a savage death) Sarah picked over the dead woman’s belongings, like a famished vulture pecking at a rotting carcase. On Christmas Day, James bagged up the bits; the head in a silk handkerchief, her limbs in a tradesman’s bag and her torso in a brown hessian sack, as at the base lay a scattering of wood shavings. On Boxing Day, he boarded a horse-drawn carriage bus with a blue tradesman’s bag and - in separate journeys - discarded the bits of his betrothed far across the city – in the West, the East and the South – with her limbs later found in a field in Brixton, her severed head blocking the canal lock in Stepney and her frozen torso hidden behind a large stone paving slab by the toll-booth at Pineapple Gate. Having neither heard a peep from Hannah or James since Christmas Eve - believing she had either fled in shame, eloped in joy, or (as she had originally planned) was living overseas - no-one reported her missing. So, for the next few months, having preserved it in vinegar, the head of Hannah Brown was put on display in a pickling jar at the Paddington Workhouse, but no-one was able to identify her… Not until three months later, when hearing word that the mysterious severed head had salt & pepper hair, short thick teeth and a healed slit down her left ear-lobe – although the bloodless skull was gaunt and deformed – William identified it as his sister and James Greenacre was arrested. (End) On the evening of Sunday 24th March 1837, having obtained a warrant, Inspector George Feltham entered a rented lodging at 1 St Alban's Place in Kennington, where he found James and Sarah in bed together. To the side were three large trunks stuffed full of the deceased’s worldly possessions; a black silk cloak, a black boa, a distinctive white shawl, and – of the pieces they hadn’t pawned off, such as rings, gowns and handkerchiefs – were the gold pinchbeck pocket-watch and the set of pearl earrings. The Policeman’s timing was very fortuitous, as having already booked a ship’s passage for the next day, by the break of dawn, James, Sarah and their son would have set sail to Canada – never to return. Upon his arrest, having become a media sensation especially in the trashy penny-dreadfuls which lapped up every gory detail of the corpse’s demise, although James relished his new-found fame – like a coward - he stuck to his story about an accident and he branded Hannah as drunk, loose and in debt. On 10th April 1837, James Greenacre and Sarah Gale were tried at the Old Bailey. Sarah as an accessory after the fact and James for wilful murder, to which they both pleaded ‘not guilty’. But after a two-day trial, having deliberated for just two minutes, the jury returned a unanimous verdict of guilty. Sarah Gale was transported to Australia where she would live for the rest of her life. Where-as, on the 2nd May 1837 at Newgate Prison, at the hands of an equally sadistic executioner such as he, known as William Calcraft, James Greenacre entertained the baying crowds with a dangle and an odd little dance at the end of a taut hemp rope, until – after six interminably long minutes – his feet stopped twitching. His death was agonisingly slow, but for the greedy few who sold grisly memorabilia, it was profitable. But this story isn’t his. Hannah Brown was a lovely lady with dreams of living the life which she truly deserved. She was strong, smart and independent. She didn’t need to marry, but she loved to be loved, so in her twilight years, she knew she didn’t wish to be alone. She thought she had found the perfect man, a loving widower who was so similar to her in so many ways, but all he ever loved was her money. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. If you’ve not been too grossed-out by the grisly details of the scattered remains of Hannah Brown, there are a lot more details which didn’t make it into the episode which I can share with you in the next instalment of Extra Mile after the break, as well as some of the usual nonsense. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporter who is Fiona Montgomery, I thank you very much, as well as a thank you to Selina Dean for your very kind donation via the Murder Mile e-shop. Plus a big thank you to everyone who sent lovely messages saying how much they enjoyed How To Get Away With Murder. It was a much-needed deviation from the usual Murder Mile gloom, which we all need at the moment (given how crappy the year’s been) so I’m glad you liked it. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND TEN:

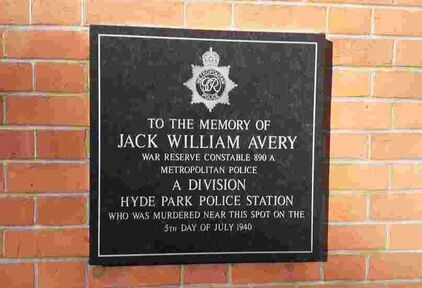

On Friday 5th July 1940 at 13:45pm, War Reservist Constable Jack William Avery left his post at the 'Old Police House' in Hyde Park having been alerted to a man "acting suspisiously" near the gun-emplacements. Confronting the man, PC Avery was stabbed in the left thigh and died the next day of blood loss. PC Avery is one of 1600 police officers to have died since policing began... but is there more to this story, why did he die and who was Frank Stephen Cobbett?

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of the gun emplacements in Hyde Park is where the black triangle is, just to the right of the Sepentine in Hyde Park. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

Here's two little videos of the locations for Ep110: A Memorial to The Fallen. On the left is the Old Police House in Hyde Park where Constable Jack Avery was based and the location of the gun emplacements which Frank Cobbett was sketching. This video is a link to youtube, so it won't eat up your data.

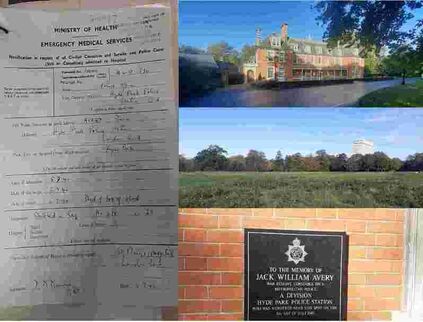

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable. On the left is the medical report marking Jack's arrival in hospital, his injuries and his death. On the right is the Old Police House, the location of the gun emplacement and the memorial.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0. SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified polcie investigation files held at the National Archives, as well as many other sources.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about a memorial to a police constable who died in the line of duty. On the plaque is inscribed his name, his rank and a few details about his tragic demise, but one key detail is missing; as there was also a man with a name and a rank who (some may say) deserves to be remembered too. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 110: A Memorial to The Fallen. Today I’m standing in Hyde Park, W2; a leisurely stroll west from the site of the Hyde Park bombing, a short dawdle south of the three possible robberies or murders of Vincent Patrick Keighrey, a brisk walk north from where John George Haigh toasted his old pal William McSwan before dissolving his body in acid, and a little saunter from the ice disaster on the Serpentine - coming soon to Murder Mile. Perched near the border of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens is the ‘Old Police House’; a three-storey brown-brick Queen Anne-style lodge built in 1902; with crisp white window sills, a neatly manicured garden and Victorian street lamps. If anything, it looks more like a manor house than a police station. The Royal Parks Keepers (as they were known until 1974) were a police constabulary separate from the Metropolitan Police who were there to keep peace and order in London’s royal parks, with some constables living in the park’s many lodges as well as working inside of the Marble Arch itself. Today, as a constant wail of sirens encircles Hyde Park, inside the lush greenery of this 350-acre former hunting ground, life is a little more sedate than in the city itself. It’s not without crime, as there’s often a rogue barbeque to extinguish, a noisy stereo to quieten, rowdy crowds to quell at Speaker’s Corner and the endless theft of phones from a long procession of posing pouting narcissists who believe that Instagram isn’t worth tuppence unless it’s chock full of shoddy videos of their stupid grinning faces. But during World War Two, the policing of Hyde Park faced some truly challenging times, as it wasn’t just an escape for the city’s civilians or a pasture for the grazing sheep, as to protect the city from the daily onslaught of Messerschmitt’s and Heinkel bombers from the German Luftwaffe, Hyde Park was a strategic military base complete with soldiers, barracks and a radar station, as well as defences and offensive weapons such as barrage balloons, rocket-batteries and gun-emplacements. Largely undocumented, much of Hyde Park’s war-time history has been lost to the winds of time, and although a memorial rightfully stands at the ‘Old Police House’ to Constable Jack William Avery - who gave his life doing his job and protecting the city - this is not a story about one fallen hero, but of two. One who is remembered in death, and the other who was forgotten while he was still alive. As it was here, on Friday 5th July 1940 at 13:45pm that Constable Avery left his post on a routine job, where two very different heroes would meet, and their lives would be changed forever. (Interstitial) On 5th July 2007, a memorial to mark the 67th anniversary of the murder of PC Avery was held at the north-east corner of the ‘Old Police House’. In attendance was the Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Ian Blair, the officers of the renamed Royal Parks Police and - following a mass media appeal by the superintendent - Margaret Penfold, who was a distant relative of the deceased constable. With the gloomy sunless sky speckled with scattered showers which reflected the sombre tone of this lost summer’s day, Jack’s death represented one of more than sixteen thousand officers who had died in the line of duty since policing began in Britain, including fourteen who would be killed that year alone. To honour him, on the brown-brick wall of his former-station was placed a grey square slate etched with the Metropolitan Police emblem, and in a white Arial font (as used by the UK Police) were these few words; “to the memory of Jack William Avery, war reserve constable 890A, Metropolitan Police, A Division, Hyde Park Police Station, who was murdered near this spot on the 5th day of July 1940”. To the many people who pass this plaque, this is all they will ever know, as it says very little about him, and to be honest we know very little about him. Like so many ordinary people who died to give us the freedom we often squander - as Jack wasn’t a lord, a general or blessed with wealthy benefactors who would ensure that a rose-tinted view of his potted history would be nationally marked with reverence and honour – the details of Jack’s ordinary life are as scant as the words on his own memorial. Jack William Avery was born on 5th November 1911 in Bromley (a borough now in south-east London but back then it was a parish in Kent). As the only known child of a 29-year-old mechanic and chauffeur called Frank Gerard Avery and a 30-year-old teacher called Bertha Wilding, Jack was born and raised in an ample lodging at 5 Northall Villas in the nearby borough of Mottingham. Their income was small, their home life was happy and although his birth was unexpected, he was no less loved. Being educated locally, Jack was described as a “good student” although he was nothing exceptional, he passed his school certificate and – just like his father – he trained as a motor mechanic, but being short, asthmatic and cursed with bad eyesight, Jack’s career options were always going to be limited. Described as kind and polite, Jack was a slightly built peaceful young man with old-fashioned manners, who would always tip his hat to a lady, open doors for mothers and never forgot his p’s and q’s. By 1939, being recently engaged, earning a wage and living with his fiancé in a small flat, Jack’s little life was as good as anyone else’s in those turbulent months before the world was plunged into war. Keen ‘to fight for King & Country’, on the 3rd September 1939, 28-year-old Jack marched down to Lord’s cricket ground to enlist in the armed forces. Experience wasn’t necessary, as all the right recruit needed was four simple things; to be young, fit, eager and healthy. But of the four, Jack only had three. Listed as ‘4F’, there were many reasons why a seemingly healthy young man like Jack could fail his medical and be declared ‘unfit to serve’, in Jack’s case it was his height, his sight and his weak lungs. Still eager to ‘do his bit for Britain’, that very same day, Jack enlisted as a War Reserve Constable for the Royal Parks Keepers, based at ‘The Old Police House’ in Hyde Park, and he did his parents proud. For such a slight man, it was an odd career, but with the city bludgeoned by a constant bombardment, the park under military control and the air thick with suspicion as possible foreign agents lurked within, being in a time of great mistrust and uncertainty, his role was no less vital. And yet, Jack’s new job and its location perfectly suited his mild demeanour as – although his humdrum routine would often be interspersed by the swift crack of cannon fire and the brilliant flash of surface-to-air rockets – he liked being an officer who peacefully patrolled the lush green oblong of ponds, trees and sheep. Only, of the six years the war would last, Constable Avery would serve only ten months and two days. On Friday 5th July 1940, at 1:45pm, having been alerted by a keen-eyed member of the public who had seen a dark suspicious figure lying-low in the thick grass, furtively making notes with a pad and pencil of the arch of allied gun emplacements positioned at the north-west edge by Lancaster Gate, although unarmed, PC Avery dashed to the scene and in the pursuit doing of his duty, he was stabbed to death. His murder would leave his elderly parents childless and his grieving fiancé without a husband-to-be. That was his story and (of course) it warrants a memorial for the sacrifice that this selfless hero made, but this is only half of the story, as (unusually) the other hero in this tragic tale… was his murderer. His name was Frank Cobbett… but very few people would know that, or even care. Frank Stephen Cobbett was born on the 21st November 1897, in a small one-roomed lodging in a tiny tumble-down house at 19 John Street in Battersea, an industrial wharf-strewn part of South London. As the third eldest child to John Cobbett (a builder) and Mary Ann Taylor (a housewife) - just like his two older siblings Thomas and Ellen who were shamefully conceived out-of-wedlock - by the time that both parents had scraped together a little money to marry, Mary Ann was very heavily pregnant, the wedding was a shotgun affair and Frank would forever cursed with the cruel title of a ‘bastard’. Aged four, with Mary Ann’s mother in-tow, moving to a slightly bigger but equally tiny brown-bricked cottage at 28 Mullins Path in Mortlake, this family of six, soon to be seven, lived a life which was hard, cold, cramped and chaotic. Fights were frequent, food was scarce and tragedy would soon strike. In 1907, when Frank was only nine, his mother died. In need of a wife to care for him and his children, John Cobbett hastily married a recent widow called Ada Coxen barely one year after his wife’s death, and in the two cramped rooms of their squalid little cottage now lived a family of twelve; including Frank, his dad, his dead mother’s mum, his three siblings, a step-mother, four step-siblings and a new baby on the way. Frank was devastated at his mum’s death but equally distraught at his dad’s betrayal. Being a little slow at reading and writing, Frank scraped through a basic education; he was unskilled, uneducated and (as tradition dictated) doomed to follow his father in the trade of being a brick-layer. Disliking his dad, bored with his lot in life and eager to escape a tough upbringing in which he felt very little love; Frank was prone to outbursts of anger - a flaw which could only be cured by drawing. He wasn’t a great artist and his talent was only so-so, but he was only truly calm and content when he was sat in the sun, lying on his belly and breathing softly, with a pencil and pad in his hand, sketching. Everybody has a hobby, this was his… and yet, the soothing act of drawing or doodling would guide Frank through some of the darkest moments of his turbulent little life, many which lay right ahead. On 12th December 1917, three years into the First World War, with the Influenza pandemic wiping out troops faster than any bullets, bombs and mustard gas could, and with the Army in dire need of ‘fresh meat for the grinder’– just like Jack Avery – Frank grabbed his conscription papers and enlisted. Unlike Jack - being young, fit, eager and healthy - Frank ticked all the boxes, and against his father’s wishes (being a veteran who had witnessed at first-hand the horrors of conflict), after a bitter row so fierce that neither would speak to the other again – Frank Cobbett went to war. And for the very last time, he would have a name, a rank and a few scant details which marked his life and his demise. Having passed basic training, 20-year-old Frank Cobbett became Private Cobbett of the 3rd East Kent Regiment and was shipped off to the boggy blood-soaked quagmire of the French frontline to bolster the beleaguered 230th Brigade of the 74th Division. With the brooding skies thick with an acrid smoke, the mud often knee-deep and the vile stench of rotting flesh as dead comrades died where they fell – being too dangerous to move or bury, so often many bodies became makeshift sandbags – living on a diet of death, disease and depression - like so many men - Frank was subjected to horror after horror. And throughout this bloody conflict, although he’d been issued a Lee Enfield 303 rifle, the thing which truly saved his life and his sanity was his pad and pencil; a little hobby which kept him calm, was used by his superiors to sketch the enemy positions and kept up the moral of his war-buddies with portraits. On 11th November 1918, with the war officially over, the enemy having surrendered, twenty million people dead and twenty-one million wounded, as memorials were erected to those brave souls who had selflessly given their lives so that we might live, the unsung heroes who had survived fought on. Following the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of 1915 to 1918, along with the 10th Battalion comprising the Royal East Kent and West Kent Yeomanry – with barely a day to catch their breath - Private Frank Cobbett and his compatriots were sent to Egypt to defend a key strategic point at the Suez Canal. Just like Jack, he did his part for King & Country. Just like Jack, he would be hailed a hero. And just like Jack, his service would be short, as although the aftermath of the First World War would rage on for many years and decades, Private Frank S Cobbett would serve for only fifteen months and three days. On an unrecorded date in February 1919, while doing his duty, Frank was cut-down by an enemy bullet which hit him squarely in the chest, and although this fast-hot-lead had missed any vital organs, blood vessels and (crucially) his spine - leaving him with what seemed like just a small hole in his right breast – the force had blasted-out a chunk of flesh from his back ripping him open from shoulder-to-shoulder. Frank was lucky to be alive, and although his war was over, the pain and trauma was not. On 15th March 1919, being patched-up and shipped home, 21-year-old Frank was discharged from the army, he was given two medals, a bottle of painkillers and a pitiful pension of eight shillings a week (a fifth of the working wage) and like so many battle-scarred veterans who had returned all broken, the soldiers who died were rightfully remembered, but those who had survived were cruelly forgotten. Still furious at his father and unwilling to embrace his family, Frank tried to return to a normal life, but this once-eager boy had died back in Suez and – although barely two years older – what now remained was a moody sullen shadow of his former self, crippled by constant pain and dumped by his country. Unable to carry a hod of bricks on his shattered back, this fit young lad could no longer earn an honest wage as a labourer. He worked for three years on-and-off as a brewer, but plagued by pain, in 1923, he lost his last regular job. And being barely literate and increasingly angry, his options were limited. Over the next two decades, as life for the average civilian returned to normal, Frank became invisible. He had no home, no job, no money and no help. His family were gone, his friends had disowned him and he had no wife, girlfriend or kids. Unable to adjust, Frank became a nobody, a nothing, who drifted from day-to-day, place-to-place and doorway to park-bench. To the many thousands who passed this vagrant slumped in the gutter, they didn’t see him as a hero, but as a dirty shambling wreck who lived out of hostels, begged for spare change and foraged for food scraps in the bins. Frank Cobbett had disappeared and like so many ordinary heroes who gave their health, life and sanity to protect us - with no title, rank or wealth to ensure they would be fondly remembered by strangers – the only reason we know anything about his life after his war-time service is by his criminal record. On 7th February 1930, at Nottingham magistrates court, he was sentenced to one-month’s hard labour for smashing two windows at Trent Bridge in a pique of anger. Returning to London and living rough, he received four further sentences in quick succession; on 13th June 1932 he was bound-over for three years for begging, on 20th February 1933 he served fourteen days hard labour for begging, on 7th April 1933 he served ten days hard labour for assaulting a policeman, a further day in prison on 5th February 1934 for begging, and on 1st October 1935 he was fined £2 for vagrancy. His crime? Being homeless. We know he was local as he was tried at Bow Street and Marlborough Magistrates Courts, his prison stints were at Brixton, and he withdrew his meagre army pension at the Shepherd’s Bush Post Office. By 3rd September 1939, as motor-mechanic Jack Avery enlisted as a War Reserve Constable based at the ‘Old Police House’ in Hyde Park, former Private F Cobbett of 3rd East Kent Regiment had been alone and isolated from a hearty meal, a warm bed and even just a simple conversation with another person for almost two decades. In fact, the most contact he’d had with another human-being of recent was the bruises, cracked ribs and a fractured jaw he had sustained having been beaten-up by a cowardly gang of drunken louts who had attacked him - all because he was weak, dirty and vulnerable. For longer than any human should endure, Frank lived alone, he lived in fear and terrified of being attacked again he was armed with an old rusty kitchen knife he had found at the bottom of a bin. But as lonely as his life was, he still had one love which would always comfort him – drawing. As no matter how poor he was – even if all he could find was a broken stub and an old bit of chip-paper – Frank always found solace by sitting quietly and sketching. It was just his little hobby to pass the time… …but life was against him, his lifestyle was illegal and the law would soon conspire to cause him to kill. Friday 5th July 1940 was a crisp clear day, as Frank quietly lay in the thick grass of Hyde Park, soaking-up the sun along-side the grazing sheep. On his body was his one set of clothes, in his pockets were his worldly possessions (a shaving razor, a pension book, 13 shillings and 6 pence) and in his hands he held a short stubby pencil and a square memo block of paper. And where-as once this had been a calendar - with every page left empty and blank - instead he used it to sketch. Sometimes he’d draw a tree, sometimes a street, sometimes a pond full of ducks and geese, he kept to himself and was no bother to anyone, but today he decided to draw something a little more exciting. Perched by the north-west corner of Hyde Park, a short walk from Lancaster Gate, sat one of the city’s military defences - as with barrage balloons by Kensington and a volley of rockets by Park Lane – the 263rd battery of the 84th Royal Artillery Regiment had positioned an arch of four 3.7-inch mobile anti-aircraft guns, with corrugated Nissen huts and a GL Mark IA radar unit. It was still an unusual sight for a public park, so people often stopped, looked and chatted to the soldiers… but instead Frank drew. There were two laws which made Frank a criminal without him raising a single finger. The first was old and he knew it well – The Vagrancy Act of 1824 – having been arrested three times for being hungry and homeless. But the second was new, very new, as having only received Royal Ascent in Parliament ten months prior, the Defence Regulation Act of 1939 were emergency powers to force British civilians onto a war-footing. It implemented a nationwide blackout, emptied prisons to make way for spies and looters, it criminalised German-owned businesses, requisitioned factories to make munitions, public parks to become military defences, and – to protect the people from the threat of the enemies within – it became illegal to photograph or draw any military bases, buildings or gun-emplacements. But how would Frank know that? After almost two decades of solitude with no-one to talk to, no-one to hug and being barely literate, he wasn’t a threat or a spy, he was just a broken war-hero, abandoned by the country he had fought for, who kept himself busy by doing the one thing he loved – drawing. Only, to those who didn’t know Frank – as a person - he was dirty, strange and suspicious. At 1:45pm, a 40-year-old carpet-fitter called George Bryant ran to the ‘Old Police House’ to alert them to “a strange man” who was “hiding in the grass” and seemed to be “making notes about the guns”. Doing his duty, Constable Jack Avery dashed to the scene to apprehend the enemy; what he saw was a man dressed in black, lying low in the grass, his eyes furtively spying and his hand secretly scribbling. As Jack cautiously sidled-up behind this possible Nazi collaborator and potential traitor to the people, the PC barked “what are you doing?”. Unused to contact and fearful of others, Frank mumbled “what’s it got to do with you?”. Unhappy with his reply, Jack snatched-up the pad to see for himself, and although to many it was nothing but a block of tatty paper, to Frank, his sketch-pad was everything. As his blood boiled, Frank bellowed “fuck off” as he got to his knees. Seeing a knife where his body lay, to defend himself Jack grabbed his truncheon. To defend himself, Frank pulled a knife. As Frank swung, Jack dodged and cracked Frank hard across the head with his truncheon and as the constable blew his whistle to call for back-up, Frank drove the five-inch blade deep into the top of Jack’s left leg. Dashing to aid the injured officer, Constable Hyman Krantz blocked the assailant’s sight with his cape, and – while temporarily blinded - Jack whacked Frank once more on the head to subdue him, and as both men fell; Jack bled profusely as barely conscious Frank muttered something incoherent. Pinned to the ground by two burly men, Frank was arrested and charged with the malicious wounding of a constable, to which his only reply was “I was drawing the guns, that’s all". Cruelly, on every witness statement given that day, Frank is described as a “low moral person”, “odd” and “looking like a tramp”. PC Avery was rushed to St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, suffering a single stab wound to his left thigh and groin which had struck the thighbone and split the femoral artery and vein. Given two transfusions and an emergency operation, sadly Jack died at 8:20am of blood loss and shock. His father was by his side as he passed, but unable to reach her in time, his fiancé never got to say goodbye. (End) At 11:15am on Saturday 6th July 1940, 42-year-old Frank Stephen Cobbett, a vagrant of no-fixed-abode was charged with the murder of 28-year-old Constable Jack William Avery. Held at Brixton Prison, his medical assessment described him as “an uncouth type, insolent and mentally low”, but there was no mention of the sacrifice he had made to defend his country, or how shabbily he had been treated. In a short trial, at the Old Bailey, on 15th July (just ten days later) Frank Cobbett was found guilty and on the 22nd he was sentenced to death and to be executed by hanging. But following an appeal, which stated that both men were equally as culpable for their actions, his sentence was reduced from the capital charge of murder to the lesser offence of manslaughter and he would serve 15 years in prison. He did his time, he was released and very little else is known except that he died in 1980, aged 82. Having died in the line of duty, Constable Jack William Avery was buried, his name is listed on the Met’ Police ‘Roll of Honour’, and – rightfully – he has a memorial to remember the sacrifice that he made. It’s great that we live in a country where an ordinary person doing their job can be immortalised for the courage and bravery they’ve shown, rather than always being ordered to applaud a lord, a general or a politician who (by the size of their statue) states that they deserve our thoughts, tears and respect. But too often, we remember the dead and we mark the fallen, but too easily we forget those who are still serving and struggling with the physical, mental and psychological trauma they have suffered and continue to suffer - beyond their loyal service - by fighting for our rights and freedoms. Constable Jack Avery was a hero, as was Private Frank Cobbett; the difference was that one was a man with a job, a house and wife-to-be, and the other was a nobody with nothing but a pad and a pencil. Every hero deserves to be remembered, so until there’s a plaque for Frank, his will be his memorial. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. We’ve got nine more weeks of your regular Murder Mile episodes as well as a big multi-part finale to bring us up to the end of the season, which has taken ages to research, and up next is Extra Mile after the break, which takes no effort at all; none, nothing, zero, zip, it’s as easy as pie, or eating pie. Yum! Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Liz Tibbutt, Roy Harris, Simon Sandells, Sher Bowie and Fiona McCulloch, I thank you all for your support, it’s much appreciated, as in these difficult times Patreon has become my main source of income. Plus a big welcome to anyone who’s new listeners to the podcast and a big thank you to those who continue to support it. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

This is a hypothetical exploration into the possibility or impossibility of getting away with murder, which over four episodes covers motivation, methods, surveillance, research, eacape and clear-up, as well as the legal ramifications of planning a murder of a victim called Bob... who is fictional.

HOW TO GET AWAY WITH MURDER - PART FOUR: UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT Let’s pretend that I’ve committed a pre-meditated murder and the target was my old pal Bob. But don’t fret my friend, I’m sure you’ll get an invisible invite to the fictional funeral of this imaginary man. Was his killing perfect? Yes. Did it look like natural? Of course. Was it a bloody death in which Bob was pumped full of helium and popped like a large lardy balloon, or fed bum-first into a wood-chipper as his minced-up entrails were spattered along a wall in Morse code which read “this was an accident, honest”? No, I killed him in the dullest way possible, by lacing his pizza with an untraceable poison which was only toxic to his body… a salad leaf. Will this murder be talked about? Will books be written about it? Will the ‘salad leaf killing’ of Bob become the latest hit podcast series which true-crime fans will endlessly drone on about even though it’s not actually that good? No, but then, that was the point. As the hard part isn’t the murder, the real challenge is to get away with it. So, in this final part of this four-part series I shall attempt to ensure that I’m never suspected or arrested for the hypothetical murder of a fictional idiot called Bob… and soon, that cakey-Eva portrait will be all mine. Sigh! My name is Michael, I am a murderer, and this is How To Get Away With Murder. Part Four: Clean-Up & Escape. Dear friends. I regret to inform you that last week, Bob died. Boo hoo! Boo hoo! He was forty years old but he didn’t look a day over sixty-eight. He leaves behind a dirty sofa, the washing up and a basket of unwashed underpants. He will be sorely missed by Iqbal ‘Luigi’ Singh, the owner of Pizza Schmucks who may have to hock his diamond encrusted pizza cutter and sell his pepperoni coloured Bentley as with Bob’s pizza app’ now silent, Luigi’s cash-cow has gone to the big abattoir in the sky… literally. Bob died “peacefully” (in inverted commas) doing what he loved best; dribbling, snoozing and slobbing about, gorping at brainless shite on his telly box, while scratching his arse, adjusting his dangle fruits and feeding an endless conveyor of pizza slices into his gob using that ‘very same hand’. Urgh! His death was quick, natural and unremarkable, so much so that when the Police, Fire or Ambulance arrive, the main thing they will do is notify the next-of-kin, and not initiate a criminal investigation. If I’m smart, no-one should ever know that this was a murder, but sadly some killers really aren’t that smart. In fact, when they are finally caught, it’s not the diligence of a detective which leads to their arrest, often it’s their own stupidity and arrogance which trips them up first. For example:

So, what if Bob realised the Pizza Guy was me? What if he choked on the salad leaf? What if the tearing sound I heard was his sweaty blubbery bulk actually separating from the sofa, and being so shocked at the sight of him standing-upright – which was only possible as the calcified sweat down his back had formed a makeshift spinal brace and (although his leg muscles had withered like the two last chicken drumsticks in a party bucket) several decades worth of cola splashes had harden like seaside sticks of rock – as we wrestled to the death (with Bob angry but always keeping an eye on the telly as The World’s Craziest Celebrity Patio-Makeover Home-Video Accidents from Hell on Ice was on, and me, dodging drinks cups and urine pots, with one foot in an old spag’ bol’, another in a congealed bowl of custard and standing awkwardly, as being so close to my prized portrait of lovely Eva gently teasing me with a jammy mouthful of Battenberg, it is difficult to wrestle an angry sweaty man whilst you’ve got an erection), it was then that I accidentally slit his throat with a pizza cutter, and maybe kicked his bonce about the bedsit a bit, while playing keepie-uppie and using a lamp-shade as a basketball hoop? Now, that didn’t happen, but if it did? How do you dispose of a brutally massacred corpse in a regular domestic house? If you listen to too much true-crime, you may think “oh that’s easy”, but it isn’t. The average house isn’t equipped with the tools for a full body disposal; we don’t all own axes, chainsaws, flame throwers, wood chippers and two hundred gallons of sulphuric acid, and if we did, the Police would see that as pre-meditation. So, let’s get realistic. Can you dispose of a body in a house? No.

As planned, Bob’s death looks natural; he will be found slumped on his sofa, in front of his telly, with an endless conveyor-belt of food being fed into the huge chomping hole in his face. There are no signs of injury, assault, interference or poison, so they will assume that he choked. But how do I ensure that his death definitely looks natural, and that the Police don’t suspect that someone else was involved? Here’s a few possible suggestions which may work a treat:

To be honest, courtesy of some seriously (if entirely fictional) research and surveillance by himself, Bob’s ordinary clothing, his homelife and his lifestyle perfectly match his method of death, so nothing needs to be added… unless I wanted to dob someone else in for my crime. So, I could:

Think about this; The Golden State Killer was arrested using the DNA on a single disposable coffee cup, so I could easily scatter a half-eaten sandwich found in a bin, a smelly old sock left in a laundry or a manky ear-wax coated cotton bud at the scene to implicate someone else, but I won’t, as that would cause the police to investigate this as a murder, which is exactly what I don’t want them to do. But what if I have left some DNA behind; maybe a hair, a print, or a long line of frothy dribble and a splatter of love-hummus by the cakey Eva porn? What should I do to hide my filthy Mickey man-muck?

These are all terrible ideas, but they are the most obvious ways that murderers try to clean-up a crime scene. Each one could erase the evidence but they all point to the involvement of a third-party. But there are a few ways to eradicate any viable DNA at a crime scene without you even being there, or anywhere near, and they all involve time, air and – inevitably – the human-factor:

Right! Bob is dead, his death looks natural and his bedsit doesn’t look like a crime-scene. Yay! Well done me. So, now that all done-and-dusted, when should I call the Police? When?! Never! Here is a simple list of idiotic things which trip up almost every serial killer and murderer all the bloody time.

That means no heads, no hands, no teeth and no trinkets. Don’t nick a celebratory cheese sarnie from the fridge if I feel a bit peckish or try on his Batman underpants (as where-as once they seemed cheesy, now they’ve got a kitsch value), as everything I steal will lead directly back to me, as the culprit. So, as much as I want to, need to, and every ounce of my soul wants me to steal it, I have to leave behind the sultry cakey fresco of the lovely Hollywood siren Eva Green devouring a mini Battenberg in a way which makes me wish I had died and was reincarnated as a cake. Sigh! This is a waiting game, but if I’m patient, it may pay-off. My hope is that his legal guardians will either sell off, auction or bin his personal possessions, and then ‘cakey-Eva’ is legally mine. ALL MINE! But until then, I must weep. But what if I am suspect number one? What should I do? Here’s my top tips for when Police Constable Arsenal Guinness drains the last can, finishes his hand-shandy and gets down to some work… for once:

If I am arrested and charged with Bob’s murder, luckily the conviction rate for murder in England and Wales is pretty low. According to the Office of National Statistics, of the 712 homicides in 2018, only 163 suspects were charged, with an average conviction rate of between 17 and 33%, and even before the cases went to court, 3% of all suspects had either died or committed suicide, and post-trial, 79% of suspects were found guilty, 14% were acquitted and 4% were convicted of a lesser offence. But how many of these were well-researched pre-meditated murders for very worthwhile cause like some cakey-Eva porn, rather than some bloke gave me a bit of a funny look? Probably none. So, let us return to where we began, with one big question - how possible or impossible is it to commit and get away with perfect murder? We all assume (having consumed one too many true-crime shows which cherry-pick a few scant details of a six-year investigation and boil them down into a handy-half-hour chunk) that killing is a bit of a doddle. But for the average person like me or you, it wouldn’t be. Mentally we’d be a mess, physically we’d shake like a leaf and psychologically we’d be broken for life. Throughout every step of the planning, the research and the execution, we would stall, fumble, panic and even though I have the perfect alibi to aid my escape – that being a fat bald man in his mid-forties, I’m entirely invisible to women, most men but thankfully not dogs– I’d either have given-up, got bored, handed myself in, or been arrested for looking suspicious before I’ve even entered Bob’s bedsit. So, to conclude, unless you are a criminal mastermind, a remorseless killer, a fictional character, or the kind of arrogant self-obsessed douch-bag who doesn’t understand that every problem is solvable, every solution is negotiable and every positive action takes vastly more effort than a negative action - if you’re willing to put in the time to try and make it work - it’ll be better for everyone. Getting away with anything illegal (let alone a murder) is next-to-impossible, so why bother? Why waste the few years or decades you have left on this Earth fuming over something unimportant, when you could savour a simple life, being happy with what you do have, content with what you don’t have, and – best of all – that no-one (including myself, yourself or Bob) will end up dead. (Bob) “Hello, my name is Bob, I am Mike’s fictional friend who is ‘very-much-alive’, and I approve this message”. Oh, and if anyone is on the look-out for a rather lovely, non-dribble coated, man-hummus-free, cakey portrait of Hollywood sex-bomb Eva Green clutching a range of Mr Kipling’s finest cakes (swoon), then apparently they sell them on eBay for £10. I know! Who knew? Next time, I’ll do my research first. Thanks for listening folks. Tatty-bye. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Part Four and the final part of How To get Away With Murder. Next week, your regular Murder Mile episodes will return. A big thank you to my new Patreon Supporters who are Tony Inglis, Sarah London and Kicha Blackstone, I thank you all muchly. I hope you entered the very exclusive competition on Patreon and they you are now the proud owners of a very exclusive Murder Mile key-ring. Ooh. Plus a thank you to everyone who leaves lovely comments when you download the freebies (like ringtones, quizzes and ebooks) in the Murder Mile merch shop – there’s a link in the show notes. I read them all and they are all very much appreciated. Up next is Extra Mile. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

This is a hypothetical exploration into the possibility or impossibility of getting away with murder, which over four episodes covers motivation, methods, surveillance, research, eacape and clear-up, as well as the legal ramifications of planning a murder of a victim called Bob... who is fictional.

HOW TO GET AWAY WITH MURDER - PART THREE: UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT Let’s pretend that I’m going to commit a pre-meditated murder and the target is my old pal Bob. But don’t fret dear friend, as the murder is made-up, the victim isn’t real and all of this is total bunkum. Do I know where to kill him? Oh yes. Do I know how to kill him? Meh. And is it a 100% fool-proof plan? Not on your nelly. But that aside, I could easily extinguish Bob’s pitiful little existence by attaching his nipple piercings to the National Grid, by stapling his lips to a drag-racer’s exhaust, or by slowly feeding him into a pasta-maker tongue-first. And yes, I have given this some serious thought. But the hard part isn’t the murder, the real challenge is to get away with it. So, across this four-part series I shall be planning and executing the hypothetical murder of a fictional idiot called Bob; soon he’ll be nothing but dust, I shall be one cakey-Eva portrait better off, and you shall keep schtum, right? My name is Michael, I am a murderer, and this is How To Get Away With Murder. Part Three: Murder & Method. Last week, we established that – owing to the complete and utter sadness of Bob’s pathetic little life; where the only person he talks to is his own shadow, that sitting on a different sofa is his version of ‘taking a vacation’ and ‘spicing-up his sex-life’ means that sometimes he’ll ‘use a different hand’ (not unlike my own, if I’m honest) – I have made the momentous decision (based on weeks of research and surveillance) to murder Bob in his small lonely little bedsit. On his pizza-speckled sofa to be precise, as that is where he feels safest, where he is isolate and – more importantly – if he actually left his flat, just once in his life, he’d probably die of fresh-air overdose and his neighbours would die of shock. Now I may be a potential murderer, but I don’t want to be responsible for a massacre, do I? Do I?! Admittedly, Bob’s bedsit may seem like a really dull place to say “tata” to his existence, given that so many infamous serial-killers have upped-the-stakes in terms of murder locations, such as;

Ah lovely. Now that may all seem very exciting, but there’s one teeny tiny problem with each of these murderers? They were all caught, trapped by their own arrogance and imprisoned by their own ego. By over-complicating a simple thing such as making someone dead, it was impossible for anyone to see either of these deaths as anything other than a murder… and where there’s a murder, there is always a murderer. So, to get away with Bob’s death, I need this to look like an accident or natural. Now, this is not going to be easy, as I am dead dirty. I am a real mucky Mickey McYuckfest and a filthy festering scuz-ball of absolute scum. Oh yes, that is a fact. In fact, you are too, genetically speaking; as with the average human being made up of roughly 10 trillion cells, as 16% of our bodies is skin, every year we shed around 8lbs (or 3 ½ kilos) of skin, we lose 27000 hairs and expel 4300 litres of sweat. Oh yeah, we are dead dirty. And give that our cells contain DNA which is uniquely-coded to us, I might as well go to the crime-scene and hand the Police a business card reading ‘Hi, I am Bob’s killer. Call me’. To avoid that, I need to erase any trace of myself before I go anywhere near Bob’s bedsit. There are a few ways I could ensure I leave no traces of my DNA behind