|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND TEN:

On Friday 5th July 1940 at 13:45pm, War Reservist Constable Jack William Avery left his post at the 'Old Police House' in Hyde Park having been alerted to a man "acting suspisiously" near the gun-emplacements. Confronting the man, PC Avery was stabbed in the left thigh and died the next day of blood loss. PC Avery is one of 1600 police officers to have died since policing began... but is there more to this story, why did he die and who was Frank Stephen Cobbett?

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of the gun emplacements in Hyde Park is where the black triangle is, just to the right of the Sepentine in Hyde Park. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

Here's two little videos of the locations for Ep110: A Memorial to The Fallen. On the left is the Old Police House in Hyde Park where Constable Jack Avery was based and the location of the gun emplacements which Frank Cobbett was sketching. This video is a link to youtube, so it won't eat up your data.

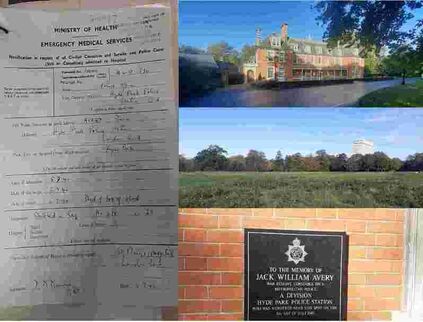

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable. On the left is the medical report marking Jack's arrival in hospital, his injuries and his death. On the right is the Old Police House, the location of the gun emplacement and the memorial.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0. SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified polcie investigation files held at the National Archives, as well as many other sources.

MUSIC:

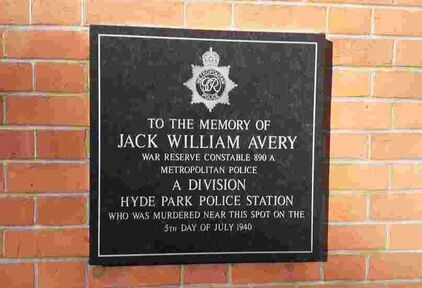

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about a memorial to a police constable who died in the line of duty. On the plaque is inscribed his name, his rank and a few details about his tragic demise, but one key detail is missing; as there was also a man with a name and a rank who (some may say) deserves to be remembered too. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 110: A Memorial to The Fallen. Today I’m standing in Hyde Park, W2; a leisurely stroll west from the site of the Hyde Park bombing, a short dawdle south of the three possible robberies or murders of Vincent Patrick Keighrey, a brisk walk north from where John George Haigh toasted his old pal William McSwan before dissolving his body in acid, and a little saunter from the ice disaster on the Serpentine - coming soon to Murder Mile. Perched near the border of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens is the ‘Old Police House’; a three-storey brown-brick Queen Anne-style lodge built in 1902; with crisp white window sills, a neatly manicured garden and Victorian street lamps. If anything, it looks more like a manor house than a police station. The Royal Parks Keepers (as they were known until 1974) were a police constabulary separate from the Metropolitan Police who were there to keep peace and order in London’s royal parks, with some constables living in the park’s many lodges as well as working inside of the Marble Arch itself. Today, as a constant wail of sirens encircles Hyde Park, inside the lush greenery of this 350-acre former hunting ground, life is a little more sedate than in the city itself. It’s not without crime, as there’s often a rogue barbeque to extinguish, a noisy stereo to quieten, rowdy crowds to quell at Speaker’s Corner and the endless theft of phones from a long procession of posing pouting narcissists who believe that Instagram isn’t worth tuppence unless it’s chock full of shoddy videos of their stupid grinning faces. But during World War Two, the policing of Hyde Park faced some truly challenging times, as it wasn’t just an escape for the city’s civilians or a pasture for the grazing sheep, as to protect the city from the daily onslaught of Messerschmitt’s and Heinkel bombers from the German Luftwaffe, Hyde Park was a strategic military base complete with soldiers, barracks and a radar station, as well as defences and offensive weapons such as barrage balloons, rocket-batteries and gun-emplacements. Largely undocumented, much of Hyde Park’s war-time history has been lost to the winds of time, and although a memorial rightfully stands at the ‘Old Police House’ to Constable Jack William Avery - who gave his life doing his job and protecting the city - this is not a story about one fallen hero, but of two. One who is remembered in death, and the other who was forgotten while he was still alive. As it was here, on Friday 5th July 1940 at 13:45pm that Constable Avery left his post on a routine job, where two very different heroes would meet, and their lives would be changed forever. (Interstitial) On 5th July 2007, a memorial to mark the 67th anniversary of the murder of PC Avery was held at the north-east corner of the ‘Old Police House’. In attendance was the Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Ian Blair, the officers of the renamed Royal Parks Police and - following a mass media appeal by the superintendent - Margaret Penfold, who was a distant relative of the deceased constable. With the gloomy sunless sky speckled with scattered showers which reflected the sombre tone of this lost summer’s day, Jack’s death represented one of more than sixteen thousand officers who had died in the line of duty since policing began in Britain, including fourteen who would be killed that year alone. To honour him, on the brown-brick wall of his former-station was placed a grey square slate etched with the Metropolitan Police emblem, and in a white Arial font (as used by the UK Police) were these few words; “to the memory of Jack William Avery, war reserve constable 890A, Metropolitan Police, A Division, Hyde Park Police Station, who was murdered near this spot on the 5th day of July 1940”. To the many people who pass this plaque, this is all they will ever know, as it says very little about him, and to be honest we know very little about him. Like so many ordinary people who died to give us the freedom we often squander - as Jack wasn’t a lord, a general or blessed with wealthy benefactors who would ensure that a rose-tinted view of his potted history would be nationally marked with reverence and honour – the details of Jack’s ordinary life are as scant as the words on his own memorial. Jack William Avery was born on 5th November 1911 in Bromley (a borough now in south-east London but back then it was a parish in Kent). As the only known child of a 29-year-old mechanic and chauffeur called Frank Gerard Avery and a 30-year-old teacher called Bertha Wilding, Jack was born and raised in an ample lodging at 5 Northall Villas in the nearby borough of Mottingham. Their income was small, their home life was happy and although his birth was unexpected, he was no less loved. Being educated locally, Jack was described as a “good student” although he was nothing exceptional, he passed his school certificate and – just like his father – he trained as a motor mechanic, but being short, asthmatic and cursed with bad eyesight, Jack’s career options were always going to be limited. Described as kind and polite, Jack was a slightly built peaceful young man with old-fashioned manners, who would always tip his hat to a lady, open doors for mothers and never forgot his p’s and q’s. By 1939, being recently engaged, earning a wage and living with his fiancé in a small flat, Jack’s little life was as good as anyone else’s in those turbulent months before the world was plunged into war. Keen ‘to fight for King & Country’, on the 3rd September 1939, 28-year-old Jack marched down to Lord’s cricket ground to enlist in the armed forces. Experience wasn’t necessary, as all the right recruit needed was four simple things; to be young, fit, eager and healthy. But of the four, Jack only had three. Listed as ‘4F’, there were many reasons why a seemingly healthy young man like Jack could fail his medical and be declared ‘unfit to serve’, in Jack’s case it was his height, his sight and his weak lungs. Still eager to ‘do his bit for Britain’, that very same day, Jack enlisted as a War Reserve Constable for the Royal Parks Keepers, based at ‘The Old Police House’ in Hyde Park, and he did his parents proud. For such a slight man, it was an odd career, but with the city bludgeoned by a constant bombardment, the park under military control and the air thick with suspicion as possible foreign agents lurked within, being in a time of great mistrust and uncertainty, his role was no less vital. And yet, Jack’s new job and its location perfectly suited his mild demeanour as – although his humdrum routine would often be interspersed by the swift crack of cannon fire and the brilliant flash of surface-to-air rockets – he liked being an officer who peacefully patrolled the lush green oblong of ponds, trees and sheep. Only, of the six years the war would last, Constable Avery would serve only ten months and two days. On Friday 5th July 1940, at 1:45pm, having been alerted by a keen-eyed member of the public who had seen a dark suspicious figure lying-low in the thick grass, furtively making notes with a pad and pencil of the arch of allied gun emplacements positioned at the north-west edge by Lancaster Gate, although unarmed, PC Avery dashed to the scene and in the pursuit doing of his duty, he was stabbed to death. His murder would leave his elderly parents childless and his grieving fiancé without a husband-to-be. That was his story and (of course) it warrants a memorial for the sacrifice that this selfless hero made, but this is only half of the story, as (unusually) the other hero in this tragic tale… was his murderer. His name was Frank Cobbett… but very few people would know that, or even care. Frank Stephen Cobbett was born on the 21st November 1897, in a small one-roomed lodging in a tiny tumble-down house at 19 John Street in Battersea, an industrial wharf-strewn part of South London. As the third eldest child to John Cobbett (a builder) and Mary Ann Taylor (a housewife) - just like his two older siblings Thomas and Ellen who were shamefully conceived out-of-wedlock - by the time that both parents had scraped together a little money to marry, Mary Ann was very heavily pregnant, the wedding was a shotgun affair and Frank would forever cursed with the cruel title of a ‘bastard’. Aged four, with Mary Ann’s mother in-tow, moving to a slightly bigger but equally tiny brown-bricked cottage at 28 Mullins Path in Mortlake, this family of six, soon to be seven, lived a life which was hard, cold, cramped and chaotic. Fights were frequent, food was scarce and tragedy would soon strike. In 1907, when Frank was only nine, his mother died. In need of a wife to care for him and his children, John Cobbett hastily married a recent widow called Ada Coxen barely one year after his wife’s death, and in the two cramped rooms of their squalid little cottage now lived a family of twelve; including Frank, his dad, his dead mother’s mum, his three siblings, a step-mother, four step-siblings and a new baby on the way. Frank was devastated at his mum’s death but equally distraught at his dad’s betrayal. Being a little slow at reading and writing, Frank scraped through a basic education; he was unskilled, uneducated and (as tradition dictated) doomed to follow his father in the trade of being a brick-layer. Disliking his dad, bored with his lot in life and eager to escape a tough upbringing in which he felt very little love; Frank was prone to outbursts of anger - a flaw which could only be cured by drawing. He wasn’t a great artist and his talent was only so-so, but he was only truly calm and content when he was sat in the sun, lying on his belly and breathing softly, with a pencil and pad in his hand, sketching. Everybody has a hobby, this was his… and yet, the soothing act of drawing or doodling would guide Frank through some of the darkest moments of his turbulent little life, many which lay right ahead. On 12th December 1917, three years into the First World War, with the Influenza pandemic wiping out troops faster than any bullets, bombs and mustard gas could, and with the Army in dire need of ‘fresh meat for the grinder’– just like Jack Avery – Frank grabbed his conscription papers and enlisted. Unlike Jack - being young, fit, eager and healthy - Frank ticked all the boxes, and against his father’s wishes (being a veteran who had witnessed at first-hand the horrors of conflict), after a bitter row so fierce that neither would speak to the other again – Frank Cobbett went to war. And for the very last time, he would have a name, a rank and a few scant details which marked his life and his demise. Having passed basic training, 20-year-old Frank Cobbett became Private Cobbett of the 3rd East Kent Regiment and was shipped off to the boggy blood-soaked quagmire of the French frontline to bolster the beleaguered 230th Brigade of the 74th Division. With the brooding skies thick with an acrid smoke, the mud often knee-deep and the vile stench of rotting flesh as dead comrades died where they fell – being too dangerous to move or bury, so often many bodies became makeshift sandbags – living on a diet of death, disease and depression - like so many men - Frank was subjected to horror after horror. And throughout this bloody conflict, although he’d been issued a Lee Enfield 303 rifle, the thing which truly saved his life and his sanity was his pad and pencil; a little hobby which kept him calm, was used by his superiors to sketch the enemy positions and kept up the moral of his war-buddies with portraits. On 11th November 1918, with the war officially over, the enemy having surrendered, twenty million people dead and twenty-one million wounded, as memorials were erected to those brave souls who had selflessly given their lives so that we might live, the unsung heroes who had survived fought on. Following the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of 1915 to 1918, along with the 10th Battalion comprising the Royal East Kent and West Kent Yeomanry – with barely a day to catch their breath - Private Frank Cobbett and his compatriots were sent to Egypt to defend a key strategic point at the Suez Canal. Just like Jack, he did his part for King & Country. Just like Jack, he would be hailed a hero. And just like Jack, his service would be short, as although the aftermath of the First World War would rage on for many years and decades, Private Frank S Cobbett would serve for only fifteen months and three days. On an unrecorded date in February 1919, while doing his duty, Frank was cut-down by an enemy bullet which hit him squarely in the chest, and although this fast-hot-lead had missed any vital organs, blood vessels and (crucially) his spine - leaving him with what seemed like just a small hole in his right breast – the force had blasted-out a chunk of flesh from his back ripping him open from shoulder-to-shoulder. Frank was lucky to be alive, and although his war was over, the pain and trauma was not. On 15th March 1919, being patched-up and shipped home, 21-year-old Frank was discharged from the army, he was given two medals, a bottle of painkillers and a pitiful pension of eight shillings a week (a fifth of the working wage) and like so many battle-scarred veterans who had returned all broken, the soldiers who died were rightfully remembered, but those who had survived were cruelly forgotten. Still furious at his father and unwilling to embrace his family, Frank tried to return to a normal life, but this once-eager boy had died back in Suez and – although barely two years older – what now remained was a moody sullen shadow of his former self, crippled by constant pain and dumped by his country. Unable to carry a hod of bricks on his shattered back, this fit young lad could no longer earn an honest wage as a labourer. He worked for three years on-and-off as a brewer, but plagued by pain, in 1923, he lost his last regular job. And being barely literate and increasingly angry, his options were limited. Over the next two decades, as life for the average civilian returned to normal, Frank became invisible. He had no home, no job, no money and no help. His family were gone, his friends had disowned him and he had no wife, girlfriend or kids. Unable to adjust, Frank became a nobody, a nothing, who drifted from day-to-day, place-to-place and doorway to park-bench. To the many thousands who passed this vagrant slumped in the gutter, they didn’t see him as a hero, but as a dirty shambling wreck who lived out of hostels, begged for spare change and foraged for food scraps in the bins. Frank Cobbett had disappeared and like so many ordinary heroes who gave their health, life and sanity to protect us - with no title, rank or wealth to ensure they would be fondly remembered by strangers – the only reason we know anything about his life after his war-time service is by his criminal record. On 7th February 1930, at Nottingham magistrates court, he was sentenced to one-month’s hard labour for smashing two windows at Trent Bridge in a pique of anger. Returning to London and living rough, he received four further sentences in quick succession; on 13th June 1932 he was bound-over for three years for begging, on 20th February 1933 he served fourteen days hard labour for begging, on 7th April 1933 he served ten days hard labour for assaulting a policeman, a further day in prison on 5th February 1934 for begging, and on 1st October 1935 he was fined £2 for vagrancy. His crime? Being homeless. We know he was local as he was tried at Bow Street and Marlborough Magistrates Courts, his prison stints were at Brixton, and he withdrew his meagre army pension at the Shepherd’s Bush Post Office. By 3rd September 1939, as motor-mechanic Jack Avery enlisted as a War Reserve Constable based at the ‘Old Police House’ in Hyde Park, former Private F Cobbett of 3rd East Kent Regiment had been alone and isolated from a hearty meal, a warm bed and even just a simple conversation with another person for almost two decades. In fact, the most contact he’d had with another human-being of recent was the bruises, cracked ribs and a fractured jaw he had sustained having been beaten-up by a cowardly gang of drunken louts who had attacked him - all because he was weak, dirty and vulnerable. For longer than any human should endure, Frank lived alone, he lived in fear and terrified of being attacked again he was armed with an old rusty kitchen knife he had found at the bottom of a bin. But as lonely as his life was, he still had one love which would always comfort him – drawing. As no matter how poor he was – even if all he could find was a broken stub and an old bit of chip-paper – Frank always found solace by sitting quietly and sketching. It was just his little hobby to pass the time… …but life was against him, his lifestyle was illegal and the law would soon conspire to cause him to kill. Friday 5th July 1940 was a crisp clear day, as Frank quietly lay in the thick grass of Hyde Park, soaking-up the sun along-side the grazing sheep. On his body was his one set of clothes, in his pockets were his worldly possessions (a shaving razor, a pension book, 13 shillings and 6 pence) and in his hands he held a short stubby pencil and a square memo block of paper. And where-as once this had been a calendar - with every page left empty and blank - instead he used it to sketch. Sometimes he’d draw a tree, sometimes a street, sometimes a pond full of ducks and geese, he kept to himself and was no bother to anyone, but today he decided to draw something a little more exciting. Perched by the north-west corner of Hyde Park, a short walk from Lancaster Gate, sat one of the city’s military defences - as with barrage balloons by Kensington and a volley of rockets by Park Lane – the 263rd battery of the 84th Royal Artillery Regiment had positioned an arch of four 3.7-inch mobile anti-aircraft guns, with corrugated Nissen huts and a GL Mark IA radar unit. It was still an unusual sight for a public park, so people often stopped, looked and chatted to the soldiers… but instead Frank drew. There were two laws which made Frank a criminal without him raising a single finger. The first was old and he knew it well – The Vagrancy Act of 1824 – having been arrested three times for being hungry and homeless. But the second was new, very new, as having only received Royal Ascent in Parliament ten months prior, the Defence Regulation Act of 1939 were emergency powers to force British civilians onto a war-footing. It implemented a nationwide blackout, emptied prisons to make way for spies and looters, it criminalised German-owned businesses, requisitioned factories to make munitions, public parks to become military defences, and – to protect the people from the threat of the enemies within – it became illegal to photograph or draw any military bases, buildings or gun-emplacements. But how would Frank know that? After almost two decades of solitude with no-one to talk to, no-one to hug and being barely literate, he wasn’t a threat or a spy, he was just a broken war-hero, abandoned by the country he had fought for, who kept himself busy by doing the one thing he loved – drawing. Only, to those who didn’t know Frank – as a person - he was dirty, strange and suspicious. At 1:45pm, a 40-year-old carpet-fitter called George Bryant ran to the ‘Old Police House’ to alert them to “a strange man” who was “hiding in the grass” and seemed to be “making notes about the guns”. Doing his duty, Constable Jack Avery dashed to the scene to apprehend the enemy; what he saw was a man dressed in black, lying low in the grass, his eyes furtively spying and his hand secretly scribbling. As Jack cautiously sidled-up behind this possible Nazi collaborator and potential traitor to the people, the PC barked “what are you doing?”. Unused to contact and fearful of others, Frank mumbled “what’s it got to do with you?”. Unhappy with his reply, Jack snatched-up the pad to see for himself, and although to many it was nothing but a block of tatty paper, to Frank, his sketch-pad was everything. As his blood boiled, Frank bellowed “fuck off” as he got to his knees. Seeing a knife where his body lay, to defend himself Jack grabbed his truncheon. To defend himself, Frank pulled a knife. As Frank swung, Jack dodged and cracked Frank hard across the head with his truncheon and as the constable blew his whistle to call for back-up, Frank drove the five-inch blade deep into the top of Jack’s left leg. Dashing to aid the injured officer, Constable Hyman Krantz blocked the assailant’s sight with his cape, and – while temporarily blinded - Jack whacked Frank once more on the head to subdue him, and as both men fell; Jack bled profusely as barely conscious Frank muttered something incoherent. Pinned to the ground by two burly men, Frank was arrested and charged with the malicious wounding of a constable, to which his only reply was “I was drawing the guns, that’s all". Cruelly, on every witness statement given that day, Frank is described as a “low moral person”, “odd” and “looking like a tramp”. PC Avery was rushed to St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, suffering a single stab wound to his left thigh and groin which had struck the thighbone and split the femoral artery and vein. Given two transfusions and an emergency operation, sadly Jack died at 8:20am of blood loss and shock. His father was by his side as he passed, but unable to reach her in time, his fiancé never got to say goodbye. (End) At 11:15am on Saturday 6th July 1940, 42-year-old Frank Stephen Cobbett, a vagrant of no-fixed-abode was charged with the murder of 28-year-old Constable Jack William Avery. Held at Brixton Prison, his medical assessment described him as “an uncouth type, insolent and mentally low”, but there was no mention of the sacrifice he had made to defend his country, or how shabbily he had been treated. In a short trial, at the Old Bailey, on 15th July (just ten days later) Frank Cobbett was found guilty and on the 22nd he was sentenced to death and to be executed by hanging. But following an appeal, which stated that both men were equally as culpable for their actions, his sentence was reduced from the capital charge of murder to the lesser offence of manslaughter and he would serve 15 years in prison. He did his time, he was released and very little else is known except that he died in 1980, aged 82. Having died in the line of duty, Constable Jack William Avery was buried, his name is listed on the Met’ Police ‘Roll of Honour’, and – rightfully – he has a memorial to remember the sacrifice that he made. It’s great that we live in a country where an ordinary person doing their job can be immortalised for the courage and bravery they’ve shown, rather than always being ordered to applaud a lord, a general or a politician who (by the size of their statue) states that they deserve our thoughts, tears and respect. But too often, we remember the dead and we mark the fallen, but too easily we forget those who are still serving and struggling with the physical, mental and psychological trauma they have suffered and continue to suffer - beyond their loyal service - by fighting for our rights and freedoms. Constable Jack Avery was a hero, as was Private Frank Cobbett; the difference was that one was a man with a job, a house and wife-to-be, and the other was a nobody with nothing but a pad and a pencil. Every hero deserves to be remembered, so until there’s a plaque for Frank, his will be his memorial. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. We’ve got nine more weeks of your regular Murder Mile episodes as well as a big multi-part finale to bring us up to the end of the season, which has taken ages to research, and up next is Extra Mile after the break, which takes no effort at all; none, nothing, zero, zip, it’s as easy as pie, or eating pie. Yum! Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Liz Tibbutt, Roy Harris, Simon Sandells, Sher Bowie and Fiona McCulloch, I thank you all for your support, it’s much appreciated, as in these difficult times Patreon has become my main source of income. Plus a big welcome to anyone who’s new listeners to the podcast and a big thank you to those who continue to support it. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|