|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND TWO:

On Friday 20th December 1940, James Forbes McCallum robbed the Coach & Horses public house in Covent Garden; he was a desperate man whose first and only robbery was ill-judged, unplanned and such a catastrophic failure that it ended in death. And yet, when he was arrested, he was so panicked, he gave the Police five plausible alibis. But which alibi was right?

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of The Coach and Horses public house at 42 Wellington Street, WC2 is where the dark blue triangle in Covent Garden is. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

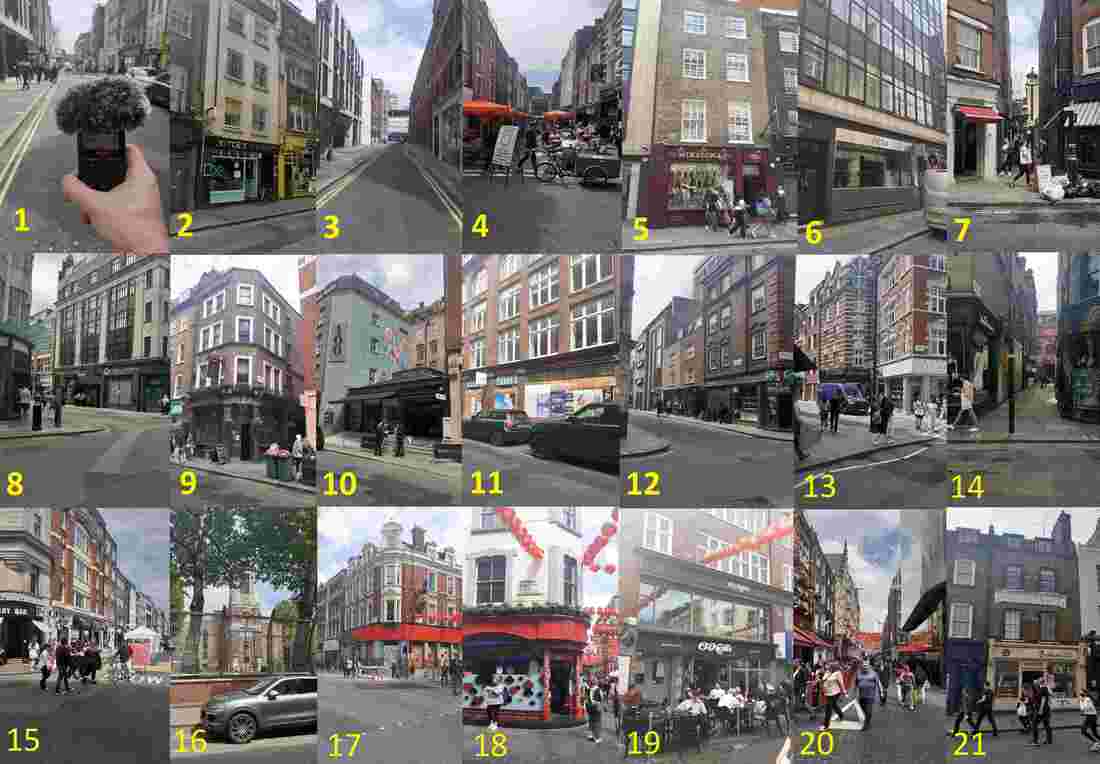

Left to right; a photo and map of the bombing of 24 Greek Street, 24 Greek as it looks today, 2 Bedford Place (the billet which James & Mac shared and where the gun was left), the Canadian Police HQ at 30 Henrietta Street in Covent Garden and The TRafalgar Hotel on Craven Street.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified police incvestigation files from the National Archives and form the Old Bailey.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE:

SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about James Forbes McCallum, a desperate man whose first and only robbery was ill-judged, unplanned and such a catastrophic failure that it ended in death, and yet, when he was arrested, he was so panicked, he gave the Police five plausible alibis. But which alibi was right? Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 102: The Five Alibis of James Forbes McCallum. Today I’m standing on Wellington Street, in Covent Garden, WC2; one street west of the brutal baker Alexander Moir, two streets north-west of the last days of Mary Ann Moriarty, a short walk from the home of the First Date Killer, and barely one hundred feet south of the former Bow Street Magistrates Court, where an infamous forensic scientist would categorically prove, without a single shred of doubt, that Dr Hawley Crippen had murdered his wife… only he hadn’t - coming soon to Murder Mile. East of Covent Garden is Wellington Street, a thin one-way street from The Strand to Bow Street which is home to the Royal Opera House, the Lyceum theatre and a wide variety of restaurants, cafés, bars and pubs. And although there’s also a museum, being British, the most important places are the pubs. We celebrate everything in pubs, whether births or deaths, commemorations or condolences, week days, weekends or (for those who don’t work hard enough) bank holidays. In fact, if an apocalypse was brewing, the British would probably all head to the pub to drown our sorrows in plop. Like most places, Wellington Street has many watering-holes; some are hideous hipster hovels serving Hoxton’s finest ale in tiny thimbles, some are brewery-owned dumps slopping-out factory produced drinks and nibbles to dull patrons who are allergic to imagination, and some are unashamedly fake boozers, where the décor of Guinness signs, old bikes, potatoes and cheeky leprechauns is so culturally insensitive they might as well have added some burned out cars, kiddie-fiddling priests and insisted that the band wears orange sashes, as the polish bar staff all utter “ta be shar”, as the St Patrick’s Day crowds flock to celebrate a world famous teetotaller by swigging back a mouthful of the “de black stuff”, only to grimace, struggle to swallow and dilute the rest of it with blackcurrant. “Aaah Jayzuz”. Thankfully, at 42 Wellington Street is a real pub. Established in 1753, The Coach & Horse is a staple of Covent Garden life. With its red-fronted facade, greenery above, a left door leading to the public bar and the right door to the saloon, this free-house is authentic, real and hospitable. It’s a great place for a pint, but eighty years ago, it was also the scene of an unplanned robbery and an unexpected murder. As it was here, on Friday 20th December 1940, that a good and decent man called James Forbes McCallum would be driven by a desperate decision to steal money and take a life. (Interstitial). James Forbes McCallum, known to his pals as ‘Jimmy’ was born on 20th Sept 1920 in Dalmuir, Scotland; a few miles north of the bustling ship-yard city of Glasgow. With his father working as a steel riveter- in the docks - being recently married with one boy born and a second soon to join their brood – his mother worked several jobs just to keep a tumbledown tenement over their heads. Known only as ‘Mrs McCallum’, his mother was a short but solid woman made of sturdy Celtic stock, who toiled away from dawn-till-dusk, from job-to-job, with one boy on her knee and one strapped to her chest. For the first few years of his life, James’ whole world revolved around his mother; she was all he would ever see or know. When she wasn’t there he screamed, but when she returned, he was soothed. As a neat and decent woman, seeing poverty as no excuse not to raise her boys well, they always knew their p’s and q’s, their manners and morals, and although she was undoubtably hard-working, she was also a little haughty. Contrasted by her rough callused hands, she wore a fine hat, a neat shawl, she spoke with an upper-class affection, and - to everyone, even her own sons – she was ‘Mrs McCallum’. On 1st December 1922, desperate to flee their grimy Glasgow slum, the McCallum’s set sail to Canada, having arrived in New Brunswick, just three days before Christmas, and set up home in Quebec. As a slightly-sickly intensely-pale child, having taken the bold but wise decision to raise her boys in the crisp fresh Canadian air, although – for the rest of his life – James would always be thin, frail, weak and prone to every cold and infection, his chance of survival was ten times better than in Glasgow. Being an average student, James was decent, likeable but unremarkable, he didn’t excel, but then, he was never in any trouble. And raised well by Mrs McCallum, after school and every weekend, James earned a small wage as an errand boy, half of which he always gave to his mother to earn his keep. In 1931, when James was eleven, his father died, leaving his mother a widower with no income. Being industrious, she turned their home at 391 Third Avenue into a boarding house, aided by her sons. But by his teens, living and working day-and-night alongside such a controlling woman, James felt trapped; he had no future, no fun and – under the harsh scrutiny of his disapproving mother - no girlfriend. Mrs McCallum wasn’t mean, she was just scared, as once her boys had grown-up, she knew she would be left with nothing. In 1938, having become unwell, she shut the boarding house. This was James’ chance to escape, and yet, it was a world-changing event which would provide him with freedom. On 5th September 1939, with Europe at war against the Nazis, eighteen-year-old James did his bit and signed-up to fight as part of Royal Canadian Regiment. Barely passing his medical, as a five-foot eight-inch, skinny and pasty-faced boy who would never see the battlefield, as part of the Canadian Provost Corps, he was assigned to protect London, as the city’s own police force had been decimated. Starting as a Private, within the year he was promoted to Acting Corporal on a wage of $80 a month, $50 of which he sent to his mother in his regular letters. Described by his seniors as a “sober, respected and an excellent officer”, he rarely drank and was never in any trouble. And as a welcome sight, being dressed in the easily Identifiable uniform of the Canadian Provost Corps - a peaked cap with a bright red top and a long grey gratecoat with a bright red emblem – being armed with a .455 calibre Smith & Wesson revolver and based out of nearby 30 Henrietta Street, James and his fellow officers were a familiar and reassuring sight, as they patrolled the streets in and around of Covent Garden market… …just one street from The Coach and Horses pub. James Forbes McCallum was well-mannered, polite and decent; he had a good career, a steady income and a bright future ahead; he didn’t argue or fight, and he had no criminal record or history of violence. And yet, fifteen months after his arrival in England, for the first time ever, in a totally unprovoked and spontaneous attack, he would commit an armed robbery and a homicide. (Interstitial) In a state of panic, as his terrified brain fumbled to find an ounce of logic in his truly abhorrent actions, James give the Police five logical (but equally plausible) alibis as to why he did what he did. Alibi #1 – Drink. Most crimes are committed whilst the culprit is intoxicated, causing a lack of judgment, co-ordination and a misguided confidence. James wasn’t much of a drinker, but in the weeks (and especially in the days) leading up to the incident, his best-friend – 44-year-old Lance Corporal John Osborne, known as ‘Mac’ - said that James had begun drinking heavily, just as he had the night before the robbery. If he was intoxicated, that could explain why his memory is so hazy, why he shouted “hands up! paper money!” but didn’t steal a penny, why he hid his face with a thick woollen balaclava but forgot about his long grey grate-coat emblazoned with a bright red emblem of the Canadian Provost Corps, and – more bafflingly – how James got shot in the arm, when he was the only person in the pub with a gun? And yet, if the barman had fought back (as James would later suggest); why did no-one hear a fight, where were the fingerprints if the barman had wrestled away the weapon, and how could two men have struggled together if there was a bulky set of brass and glass screens between them? That aside, we know that James wasn’t drunk, as – having got his dates wrong - he’d actually drank with Mac two nights earlier, barely drank the night before, and when he was arrested, he was stone cold sober. Alibi #2 – Money. Many crimes are perpetrated for financial gain, as too often, greed and needs can overrule a person’s morals and make even the most sensible do silly and spontaneous things. Sadly, a few weeks after his promotion to Acting Corporal – declared physically unwell – James was demoted to Lance Corporal. If he was broke, that could explain why he robbed the pub, why he felt forced to loan ten shillings off Mac just two days prior, why (as a good boy) he could only send $25 dollars to subsidise his sick mother in November, and why, by 14th December, just one week before, those regular payments would cease. And yet, it seems unlikely, as James wasn’t a greedy man, if anything, he was generous and charitable. Yes, he drank a little heavier, but he wasn’t a drunk or on drugs. And as a Lance Corporal, he still made a good wage, as – with his clothes, food and accommodation all paid for by the military - for the three weeks prior - he was living in a modest double-room at the Trafalgar Hotel, just off Trafalgar Square. Alibi #3 – Illness. As witnessed, thirty-two-years earlier, in the bank of Cartmell & Schlitte, just half a mile west of Covent Garden, a long history of illness and the weakened immune system of a sickly young boy had (possibly) triggered petit-mal seizures - under the grip of which - he robbed a bank, but could recall nothing. Always being pale, weak and frail, having moved from the crisp air of Canada to the chocking smog of London, James’ health had deteriorated. One year prior, having been struck down with pneumonia and pleurisy, the Army doctor had assessed James four times over the last four months – and being declared unfit – he was forced to take unpaid leave, and he was demoted, owing to his poor health. If he was ill, that could explain could explain the robbery, the shooting, the vagueness of the incident without being drunk, and how a good man could be driven to heinously break his own moral codes. And yet, even that seems a stretch, as James had no history of epilepsy nor any mental illness, he was never aggressive, delusional or disorientated. In fact, he was fully conscious of his actions. Being fit to stand trial, he didn’t take the insanity plea and although his memory was a little vague, he pleaded ‘not guilty’ to murder, as he knew the barman, he liked him and the two men had never had any issues. So, the question wasn’t if he had consciously done it. He had. The question was why? Alibi #4 – Trauma. The human body is a marvel of self-repair; skin can heal, blood can clot and bones can mend, but the hardest injury to recover from after an incident isn’t the physical affects but the psychological ones, as although the brain may escape unscathed from an unimaginable horror, trauma can still remain. On Friday 11th October 1940 at 12:35am, three days into the Blitz, a high-explosive bomb hit 24 Greek Street in Soho. It demolished the building, erupted the gas main and trapped dozens in the wreckage. Three people died, eight were injured and countless others escaped unhurt, but were left traumatised by this first brutal wave of bombings from the skies, as innocent civilians (going about their everyday lives) witnessed skin burned, limbs scattered and bodies blown apart, right in front of their eyes. One of those affected was James McCallum. Being psychologically traumatised by the bombing, seeing the Army doctor and complaining of a series of justifiable symptoms – such as tiredness, headaches and nerves - James drank to ease his pain, took sick leave on 16th December, and was recuperating well in quiet of Room 6 in the Trafalgar Hotel. And yet, it was unlikely that his trauma resulted in either the robbery or the murder, as the personality, behaviour, morals and attitude of James had not changed. Those who knew him said, he was still his same old self; quiet, calm, caring, keen to get back to work and was making a slow but steady recovery. Without doubt, all four alibis had (in their own small way) contributed to the crime; money had made him desperate, drink had clouded his judgment, illness had made him weak and trauma had fuelled his fragmented emotions. But these weren’t the main motivations for his crime… …as his fifth alibi was love. Strangely, having first met on the night of Friday 11th October 1940, the bomb which had blasted Greek Street apart had ignited a passion inside a passing couple and driven these two young lovers together. Swept-up in a whirlwind romance - as war-time sweethearts - twenty-one-year-old James McCallum had fallen for nineteen-year-old Irene Turnball, a local waitress and recent orphan. As a perfect match, both were quiet, shy and caring, and just as she was his first love, he was hers. In just nine weeks, they had met, fallen in love, moved into a hotel together and - one week before Christmas - they planned to be married. James had finally met ‘the one’, only there was one obstacle ahead of him… his mother. ‘Mrs McCallum’ would never approve of this girl, or any girl, as no girl would ever be good enough for her little boy, and - as she always feared - once he was gone, this lonely widow would be all alone. On Monday 16th December 1940, having slipped the best ring he could afford onto his beloved’s finger, James and Irene got engaged in the shadow of Trafalgar Square, with their plan to be together forever. On Tuesday 17th, having drank till he was insensible and being in a distressed state, James poured out his woes to Mac – his best-friend and a surrogate father-figure - who he always turned to for help, as - having telegrammed his mother to get her permission to marry - he anxiously awaited her reply. On Wednesday 18th, the day of their wedding, James received a telegram, it read; “Ridiculous idea. Seems very thoughtless towards me. I need your help”, and it was signed “Mrs McCallum”. The young lovers were distraught, their wedding was cancelled and the money they’d saved to marry was gone. On Thursday 19th, with his heart ripped apart by the gut-wrenching decision between disobeying his mother or finally finding love, although Irene was happy to wait, a furious James fired back a telegram to Canada, standing-up and damning her, with a curt “I shall marry, with your permission… or not”. That night, having prematurely signed into the Trafalgar Hotel as Mr & Mrs McCallum, the two timid lovers lay in bed, curled-up in each other’s arms, only James couldn’t rest. After months of illness, days without sleep, still half-hungover, and another night of reawakened trauma as bombers pummelled the West End, having loaned ten shillings off Mac, he knew this wasn’t enough money to get married. At 4am, James left saying he was going to buy some cigarettes. But instead, he did the unthinkable. The Coach & Horses at 42 Wellington Street had long been a family business; owned by Daisy & Harry Phillips, the pub was managed by their nephew David Sholman, with his brother Morris as bar-man. Described as a sweet and kind man, forty-one-year-old Morris, known as ‘Morry’ had only worked in the pub for the last nine months, having lost his job to the war, and although he wasn’t outgoing, the customers liked him, as he was a good man, who loved his wife, his family and kept to himself. Set on the ground-floor of a four-storey red-brick building, most of its regulars would perch with a pint on the pavement, as this small single-roomed pub was barely twenty-foot-deep by twenty-five feet wide. Dominated by a large central bar, the room was split into two; with the larger public bar to the left, and - separated by a partition - a small saloon to the right, which stands twenty people, at a push. And that’s it. With lines of tap-handles for pulling pints, spirit bottles with optics, water jugs as mixers and a tea urn for lightweights, it was a very regular pub. And as a way to serve food and to act as a security measure which kept any drunks from the booze, the bar-staff and the till, above the counter, from waist to head-height, were large brass and glass grilles with a series of spring-loaded windows. Licenced to serve from 5am, having put a £20 float in the till, Morris opened the doors and the day started as it always did… slowly. At 5:10am, fifty-four-year-old John Anderson, a short one-armed lift-operator entered the public bar, ordered a pint and sat reading the paper - he was the only customer. David was in the cellar, Dolly (Morris’s wife) was upstairs and Morris was cleaning the glasses. Less than one minute later, Morris would be dead. As James staggered up Wellington Street, with his mind clouded by equal measures of love and anger and his body stumbling with exhaustion, as this love-sick boy could only see a single solution to his problem – without his mother’s permission - he would be forced to commit his first and only crime. Only, being ill-judged and unplanned, this spontaneous robbery would end in a catastrophic failure. Outside the pub, James’ terrified fingers nervously pulled his woollen balaclava over his pale face. His breathing was fast and frantic, his head was thumping hard, and – having forgotten that his long grey grate-coat was emblazoned with the bright red emblem of the Canadian Police - fumbling his Army-issue revolver in his cold sweaty hands, James dashed into the empty saloon, intent on a quick robbery. Inside, James stammered “hands up! paper money”, only his order didn’t make sense, as with the pub having just opened, the till was full of coins. And yet, amidst the darkness of the sparsely-lit pub, with a bulky brass grille in their way, the two men couldn’t see each other, so although Morris had put his hands up and his eyes shut (in the hope that this would all go away), as James couldn’t tell if he had seen the gun, he swung open the glass of the head-height serving-hatch and poked his gun through. Only, not realising that the window was spring-loaded, the second his left hand let go, it swung back, the glass smacked the muzzle, and flipping his revolver ninety-degrees, James shot himself in the arm. The bungling bandit was dazed, confused and profusely bleeding from a self-inflicted flesh wound. The robbery was a catastrophe and – right then - he should have fled… but with his nerves frayed, his body tense and his hot balaclava riding up his sweat-soaked face, with the eye-holes obscuring any view, he hadn’t realised his mistake and thinking that the unarmed Morris had shot him, James retaliated. A single shot ripped through Morris’ throat, hitting the hard bone of his spine, the bullet then fractured into three pieces – one hit a glass panel, one hit a picture and one hit the tea urn – but the bulk of the lead had severed the barman’s spine, and – before he had even hit the floor – Morris was dead. (End) Being too panicked and traumatised by his actions, James fled empty-handed. Shaken-up, James called Mac, who rushed back to the billet they shared at 2 Bedford Place, and reassured by James that this was nothing serious, he had just “accidentally shot himself, off Covent Garden”, having dressed his wound with a field dressing and iodine, the two pals parted company. Mac went back to their base at nearby Henrietta Street, and James returned to the Trafalgar Hotel and his blushing bride-to-be. At 8am, hearing a bulletin that detectives were seeking a young Canadian Police officer in a long grey greatcoat, with a bullet-wound to his left arm – although they were friends, as Mac was a professional – he called it in. At 9:30am, four hours later, James was arrested for the murder of Morris Sholman. In a state of panic, confusion and exhaustion, being desperate to aid the Police with their investigation, although his memory of this traumatic event was a little hazy, James gave five possible (but equally plausible) alibis to his crime, all of which were back-up by witness statements and irrefutable evidence. Held at Brixton Prison, he was found fit to stand trial. Having refused the insanity plea and (as was his right) pleading ‘not guilty’ to the murder, James Forbes McCallum was tried at The Old Bailey on Tuesday 11th February 1941. After a two-day trial, he was found guilty, he was sentenced to death. On Friday 28th February 1941, a few days before his execution, Mrs McCallum died. Being distraught at the grief of losing his beloved mother, James’ won his appeal on compassionate grounds and owing to the trauma he had suffered in the bombing, and with his execution commuted to life in prison, James was deported back to Canada to serve his time. James Forbes McCallum was denied love by his mother, marriage to his lover, and being short of a few pounds for a very simple wedding, he would be forced to pay the ultimate price. James never married Irene and – being separated by a vast ocean - the two young lovers would never meet ever again. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. That was the episode, and next is Extra Mile, the non-compulsory extra bit which you can choose to listen to, or you can choose not to, I’m good either way, it’s no biggie if you don’t. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Kelly Cook, Caroline King, Neill & Sharon Waugh (happy belated birthday Sharon) and Sioned Jones, I thank you. All of you will be receiving a thank you card full of goodies, and some lucky people will receive very rare Murder Mile key-rings too. Oooh. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND ONE:

On Saturday 7th November 1908, at 11:40am, John Esmond Murphy walked into the bank of Cartmell & Schlittle at 84 Shaftesbury Avenue. Overwhelming evidence pointed to the fact that he bungled a heist, pulled a gun, shot and stabbed the manager dead, and was then captured, arrested, convicted and executed. But did he actually do it?

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of Cartmell & Schlittle at 84 Shaftebury Avenue is where the purple triangle in the middle between Soho and Chinatown is. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

Here's two little videos to aid your enjoyed / understanding of this week's episode; on the left is the murder location at 85 Shaftesbury Avenue, and on the right is a little video showing you what a typical petit mal seizure looks like. This video is a link to youtube, so it won't eat up your data.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0. SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified police incvestigation files from the National Archives and form the Old Bailey.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE:

SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about a very ordinary robbery, as the overwhelming evidence pointed to the fact that John Esmond Murphy walked into a bank, bungled a heist, pulled a gun, shot and stabbed the manager dead, and was then captured, arrested, convicted and executed. But did he actually do it? Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 101: The Fatal Seizure of John Esmond Murphy. Today I’m standing on Shaftesbury Avenue, off Chinatown, W1; one street north of the fiery death of Reginald Gordon West, one street west of the hushed-up shooting at the Rose n Dale club, a few yards from the first failed assassination on Russian dissident Alexander Litvinenko and one street south of stabbing of Savvas Demetriades and the Cypriot code of silence - coming soon to Murder Mile. This bit of Shaftesbury Avenue lies on the border between Soho and Chinatown, only being little more than a busy road from Piccadilly Circus to Holborn, it has all of the traffic but none of the footfall. With nothing to see here and nowhere to go, the tourists pass through this West End wasteland as it’s a bit of a cultural dead zone, as there are no theatres, pubs, or sights of historical interest, just two long lines of very grey, very vague buildings and a lot of exhaust fumes. And with the bustling theatres deliberately keeping their distance, it’s as if this bit of Shaftesbury Avenue is an architectural leper. Of course, to anyone who loves staring blankly at some obscure arty subtitled twaddle, losing a shirt (and a hand) in a not-so legal Chinese casino, paying £3 for a warm flat can of Kosher Cola, wasting a night being yah-d at (“yah-yah-okay-yah”) in a pretentious club by some TV tossers, or overcharged by a Chinese herbalist for an extract of tiger anus to cure your piles, then this is your promised land. A high point is at 84 Shaftesbury Avenue; a five-storey mansion block with red-brick and cream colour pillars, built in the late 1800’s, which is now home to Olle – a Korean barbeque, where many satisfied munchers (like myself) have gorged themselves silly on a wide array of mouth-watering delights. And although, this is a fabulous place to fill your belly - as it was once the bank of Cartmell & Schlitte - it is also the site of a bungled robbery, an unfortunate death and a very strange miscarriage of justice. As it was here, on Saturday 7th November 1908, that John Esmond Murphy would be fatally seized with an uncontrollable urge to steal and kill for the very first and the very last time. (Interstitial) But did he actually do it? Well, yes, he did and the evidence was irrefutable. (Dizzy sounds) It’s a fact that on Saturday 7th November 1908, at 11:40am, twenty-one-year-old John Esmond Murphy of Paddington – having purchased a four-inch sheath knife and a .455 calibre Webley Fosbery revolver one day prior – entered the bank of Cartmell & Schlitte. Being penniless, he shot the manager once, stabbed him six times in the hands and chest, a struggle ensued, Murphy fled, and in his desperation to escape, he stabbed a van-driver and a police constable, who wrestled him to the ground, and he was swiftly arrested within sight of the bank and just a few seconds after the robbery. The incident occurred in broad daylight, on a busy city street, he wasn’t wearing a disguise and he was positively identified without hesitation by several eye-witnesses who all gave detailed statements. His fingerprints were found in the bank, on the gun, on the knife and the blood had stained on his clothes. Seven weeks later, being deemed medically fit to stand trial, although he pleaded his innocence by claiming that he had no memory of the event, with his insanity plea rejected and his laughable defence being down to a dose of malaria, two bouts of sunstroke and a hereditary form of epilepsy – as the robbery was clearly premeditated - he was found guilty in a court of law and executed for his crimes. If ever there was an open-and-shut case of robbery and murder, it was this. But did he actually do it? Well, no. I don’t think he did. John Esmond Murphy, known as Jack was born in Calcutta (India) in the summer of 1886, as the second of two siblings to British parents; his mother was a housewife, his father was a sergeant-major in the Army and he had one sister called Kathleen. Originating from Ireland, the Murphy’s were a loving but ordinary lower-middle-class family seeking a better life, as the British Empire expanded across Asia. Being a sensitive little boy, with a small thin frame, brown wavy hair and a beak-like nose, Jack was neat and clean, polite and calm, quiet and meek. He didn’t shout, cry or cause a disturbance, and being an intelligent lad with a love of engineering and poetry, he had a bright future ahead of him. But sadly, the Murphy’s were a family who were cursed with bad luck, illness and tragedy. In 1896, when Jack was aged ten, the Murphy family were struck down with Malaria; a deadly disease of the blood carried by mosquitos resulting in shivers, fever and death. And although not a cure, a lifelong course of Quinine would prove an effective treatment, sadly his father would not survive. As a small sickly boy, Jack would battle typhoid, scarlet fever, cholera and severe bouts of sunstroke which would almost take his life, and even though he bravely soldiered on, his life was to get worse. In 1902, when Jack was aged sixteen, having contracted pleurisy, his mother died of a brain fever. Jack & Kathleen were two grieving teens, all alone in India and four thousand miles from their nearest living relative. Anyone else would have struggled and failed, but being educated, hard-working and fluent in Bengali, gifted a small inheritance in their parent’s will, they would thrive for two more years. Only, unbeknownst to them, both parents had bequeathed them something more than money and a home, as the biggest inheritance the two siblings would receive was the hereditary curse of epilepsy. Initially Jack & Kathleen didn’t know they were epileptic, as with its onset often occurring in puberty, to the best of their knowledge they had never had a seizure. But then, there are two very distinct types of epileptic seizure; one which affects the whole body and the other which affects the brain. Commonly known as ‘grand-mal’ seizures, these attacks have familiar symptoms like a rigid stiffening of the body, a frothing at the mouth, a loss of bladder control, consciousness, and sometimes the ability to breathe, and (most noticeably) the violent uncontrollable spasm of the whole muscular system, which can last for seconds, take hours to recover and may require medical assistance. And although both types are caused by a violent electrical disturbance in the brain, ‘petit mal’ seizures are incredibly subtle, so subtle that sometimes even the sufferer and those around them are unaware that a seizure has taken place. Known as ‘absence seizures’, although symptoms vary, often being triggered by moments of emotional stress, an ‘absence seizure’ is typically denoted by a vacant look in the eyes, a slight fluttering of the eyelids, the ceasing of a conversation mid-sentence and - being physically unharmed - they often return to normal with no memory of those missing seconds. But sometimes, an atypical ‘petit mal’ seizure may be preceded by mood swings, aggression and (like a Jekyll & Hyde) a severe shift in personality. And although during a seizure they can still walk, move and interact with the world, unlike the people around them, they have no control over their actions. Thankfully, suffering intermittently from typical ‘petit mal’ seizures, neither Jack nor Kathleen let their disability stop them from leading an active and productive life, which would make their parents proud. In 1903, aged seventeen, Jack & Kathleen returned to the UK, first to Glasgow, and then to London. Having served eighteen months as a conscientious and dedicated Private in the British/Indian Army, being trained as a mechanic, Jack earned a good reputation as "reliable, trustworthy and hardworking engineer". In 1904, he trained as a driver and mechanic for the Automobile Market on Oxford Street where the manager praised him as “an asset to the company” and “quite a gentleman”. In 1905, he became a sub-station attendant for the Underground Electric Railways Company, responsible for the power supply at Ravenscourt Park tube station, where his supervisor said he was “steady, reliable and intelligent”. And remaining in employment until March 1908, as assistant to a civil engineer, Jack was only laid-off owing to an engineering strike, where his last employer hailed him as “a very well-trained engineer, perfectly sober and the meekest and quietest individual I have ever met”. He rarely drank, he didn’t do drugs, he didn’t lead a lavish lifestyle and had no expensive tastes; he never swore, shouted or stole, he didn’t have a bad bone in his body and he had no criminal record. And as a quiet lad with few friends – outside of engineering and poetry - his one passion was target practice. Once a week, having trained as a keen and careful marksman in the Army, he enjoyed the thrill of shooting at paper targets at the King’s Rifles shooting range in nearby Oxenden Street. Keen to develop a solid career, to live a good decent life and to aid his sister who had been diagnosed with a brain tumour, Jack had never taken a day-off sick. In fact, although an epileptic would never have been hired for such roles, his petit mal seizures were so infrequent, his colleagues barely noticed. On rare occasions he appeared forgetful, distracted,tired and sometimes had a glazed and vacant look about his eyes, and one time - having loaned the boss’s bike – whilst cycling, he fell off, and was found wandering aimlessly, unaware of how he’d got there, or where the bike was… but that was it. Six months later, a court of law would conclusively prove that John Esmond Murphy had robbed a bank, inflicted two violent assaults and brutally murdered a man for money. But did he? (Interstitial) It is said that atypical seizures are often triggered by moments of great stress. By the middle of October 1908, having eked-out a meagre existence in a series of part-time jobs, even though he had moved into a modest basement flat at 145 Shirland Road in Paddington, having pawned off his personal possessions, Jack couldn’t afford to pay his six shillings-a-week rent, or even to eat. Having deliberately moved one street away to be near his only surviving relative – his beloved sister, three times-a-day Jack would visit Kathleen. Having married well, she lived in a pleasant mansion block called Delaware Mansions in Maida Vale, but living apart from her husband and with a three-year-old daughter, Kathleen required constant care as she awaited an operation on her brain tumour. Burdened by no work, no money and no purpose, with the threat of homelessness looming, no bright prospects on the horizon and his last surviving family member knocking at death’s door, although Jack was still his usual self – a meek, placid and thoughtful boy - all too often, a cloud would descent over his head, as he morphed into someone else; someone darker, more depressive and unusually angry. Over the weeks, as his frequent seizures grew stronger and longer; his eyes were cold and dead, his face was vague and distant, and his lids fluttered almost imperceptibly, as if he was on auto-pilot. And yet, now there were new symptoms; as sometimes he would scratch his left wrist until it was red-raw and bleeding, often he’d rock back and forth on his feet muttering in an incoherent mumble, as waves of epileptic attacks came one-after-the-other, and then there were his dark and violent moods. In an instant, having been the epitome of meekness and compassion, who (just seconds earlier) had been supping his tea whilst reading poetry to soothe his sister, Jack would suddenly snap and change into someone unrecognisable; who was aggressive, violent and threatening. And then, just as quickly as it had begun, it would end; he would return to his normal self, unaware that time had passed, that an incident had occurred, and unable to apologise for his actions, as he had no idea what he had done. As the rapidity of his petit-mal seizures escalated, as Jack became physically and emotionally drained by the persistent electrical assaults on his brain, it became almost impossible to work-out where old Jack ended and new Jack began. And yet, just two weeks before the robbery and the murder of the man who Jack had never met, something very sinister and out-of-character would happen. On Monday 19th October 1908, at 12:45am, Kathleen and her live-in carer called Stella Lynne had been out to Rayner’s bar in Haymarket and had returned by taxi to Delaware Mansions. Just as they had left it a few hours earlier, the door was locked, the fire was out, the lights were off and the flat was empty. Or so they thought. Having heard an odd noise; a creaking then a breathing, as if inside Kathleen’s bedroom someone was waiting, opening the door, they saw no-one but the sounds didn’t cease. And with no stranger hidden behind the door or inside the wardrobe, there was only one last place to check - underneath the bed. Striking a match, as Stella peered into the dark recess beneath, with his beak-like nose touching the bed-springs, Stella saw Jack; semi-clad, motionless and grinding his teeth, almost catatonic (as if he was asleep), but with his open eyes fluttering, and tightly gripped in his hand was a cutthroat razor. Stella was rightly terrified, as – barely a few days earlier – whilst sharing a cab into the West End with Jack, as another black mood descended, he had muttered “I am sick of this world. I am going to find my sister and end her life, and mine, and her child's". He didn’t. In fact, seconds later, he was fine and had forgotten everything he had just said, but Stella had forewarned Kathleen of this threat. That night, as Stella snatched away his razor, in an instant Jack snapped out of his strange slumber, wrapped both of his bloodied hands around his sister’s throat, and as Kathleen screamed in terror, he strangled her; his mouth wide and silent, his eyes vacant and dead, as if it meant nothing. Kathleen’s death was only stopped by Stella. And as swiftly as this attempted murder had begun, it had stopped. The incident was reported to the Police, two constables (PC Sanders and PC Hammond) attended the scene, a statement was made, but as Kathleen did not wish to press charges and Jack was now calm and unthreatening, the matter was dropped. For the next three days, although Kathleen’s throat was bruised and she couldn’t swallow, he refused to apologise, as (in his eyes) nothing had happened. This incident only formed a small part of Jack’s defence, as it was deemed irrelevant, but according to the prosecution, what happened next would clearly constitute premeditation of the robbery. On Friday 6th November 1908, at 9am, Jack reassured his landlady that he would pay his outstanding rent the very next day, only he had no money and no job. At 2pm, having loaned £4 off his sister to pay his back-rent, instead he went to the King’s Rifle gun range on Oxenden Street and bought a .455 calibre Webley Fosbery revolver, twenty-five bullets and a black handled four-inch switchblade knife. At 8pm, he sat with Kathleen, gave her a Quinine pill, took her temperature and read her Indian poetry to soothe her, as although the operation to remove a brain tumour was due the next day, being five guineas short of the full fee, her treatment looked unlikely. At 10:30pm, as she slept, he kissed her goodnight and assured her that everything would be okay, but that night, the cancer almost took her. The next day, for the first time ever, this timid boy would rob a bank and commit a brutal murder. All of the evidence proves that he did it. But was this Jack acting out of desperation in a moment of high emotional stress, or – as a ‘petit mal’ epileptic - was he caught in the grip of an absence seizure? At 84 Shaftesbury Avenue, on the corner of Macclesfield Street in Chinatown was Cartmell & Schlitte, a bank and foreign currency exchange, ran for fifteen years by George Cartmell and Fredrich Schlitte. Being barely twelve feet square, it was small and practical, but undeniably a ‘Bureau de Change’, as with large black lettering above, although impossible to see inside owing to its lightly frosted glass on both sides, in the windows (behind a locked screen) sat thirteen bowls of foreign notes and gold coins. Inside, through a thin wooden door, in an even smaller foyer was a large wooden counter with a heavy brass grille above, which kept the staff, the customers and the money at a distance. Across the counter was a neat array of banker’s books, paper bags, weights and scales, a cheque perforator and a till. And beyond an unlocked inner door to the left, behind the counter were rows of currency drawers and two safes. In total, the bank held almost £2000 in coins, notes and gold (roughly £250,000 today). With co-owner George Cartmell on leave and the manager George Calderwood heading out, the bank was left in the very capable hands his partner, 47-year old Fredrich Schlitte, a married father of two. Witnessed on the corner of Dean Street - dressed in a plain brown suit and a dark overcoat but nothing to disguise his face (not a mask or a hat) - Jack stood silently, rocking on his heels, as a trickle of blood ran freely down the red rash of his left wrist. But when questioned later, Jack could recall none of this. At 11:40am, as Benjamin Goodkin, the bank’s last customer exited the door, being unphased by any sound or sight, as if in a trance, Jack calmly crossed the busy street, a loaded gun by his side, and entered Cartmell & Schlitte; a place he had never been to before, nor had any reason to visit. The robbery was unlike any other; as with the gun outstretched and poking through the brass grille at the chest of Fredrich Schlitte, Jack never once shouted “hands up”, “this is a robbery” or “give me your money”, he didn’t utter a single warning or instruction, instead – with wide fluttering eyes – he fired. This sweet-natured and sensitive boy who had never fired a single bullet in his life at anything but a paper target, had – without provocation, emotion, words or sounds – shot Fredrich above his heart, and having fallen to the floor, as the bespectacled banker tried to defend himself with the hefty bulk of the cheque perforator, Jack – who had no history of sadism or violence – pulled out a black handled switchblade knife, and plunged the four-inches of steel into his chest, slashing at the terrified man’s hands, as the blade pierced his stomach, his bowel, his intestines, his shoulder and his left lung. And although Jack’s teeth were bared, Jack didn’t seem to be grinning with glee, but grinding his teeth. Desperate to raise an alarm as the pale boy with the vacant expression plunged the knife deep into his torso, having grabbed a brass weight, with all of his might, Fredrich hurled the half kilo lump and having smashed the locked screen and frosted front window, it landed with a thump on Shaftesbury Avenue, scattering shattered glass and almost hitting Benjamin Goodkin who’d forgotten something. Seeing Fredrich in an ever-increasing crimson pool of blood, Benjamin screamed “Police! Murder!”, alerting a constable, but the second he looked back, Jack had fled. And although the floor was strewn with almost £200 worth of paper money and gold coins, he didn’t steal a single penny. Instead, he fled down Shaftesbury Avenue towards Piccadilly Circus, at the corner of Wardour Street, he stabbed van-driver George Carter and Police Constable Albert Howe, but having his short pursuit cut-short by several passers-by, Jack was swiftly arrested, just yards and seconds after the robbery. In his cell, this small meek boy didn’t seem like a robber and a knife-wielding maniac, but having seen it all unfold with their own eyes, there was no denying that he was. Even as the constable commented that “he looked perfectly cool and calm, as if he had been out for a walk”, and yet, when questioned this placid young man always looked bemused, as he had no memory of the incident, what-so-ever. Two days later, Fredrich Schlitte died of his injuries and Jack was charged with murder. (End) The investigation was simple. Conducted by Inspector Fogwill, the robbery was conclusively proven to have been pre-meditated as Jack had purchased both weapons. His motivation was money for his rent and his sister’s operation. And although there was an abundance of irrefutable evidence to prosecute Jack – such as the gun, the knife, the fingerprints and multiple eye-witness statements from PC Howe, George Carter and (before his death) Fredrich Schlitte – there was very little evidence to defend him. Having apologised for his actions, although many colleagues testified to his placid character, they all admitted he had unusual quirks, ticks and (in recent weeks) was prone to unnatural violent outbursts. With an insanity plea dismissed, on 8th December 1908, at the Old Bailey, the medical experts (none of whom had any direct experience of absence seizures or petit mal epilepsy), all dismissed his claims. Dr Phillip Dunn, the Police surgeon stated “in my opinion, his condition was perfectly consistent with nervousness arising from his situation”. Dr James Scott, medical officer at Brixton Prison said “he was conscious of his acts and he knew whether they were right or wrong”. And with the judge deeming his sister’s deposition into his mental and physical health as inadmissible, having pled ‘not guilty’ to all charges, a unanimous jury found him guilty of murder, and on 6th January 1909, Jack Esmond Murphy was executed at Pentonville Prison for a crime the evidence proved that he did commit. But did he? OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. After the break, I go blah-blah blah, slurp-slurp-slurp, munch-munch-munch, and then we all switch off, if you haven’t already. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Christine Klassen and Beverley Cadel, I thank you. With a special thank you to Damian Twarogowski for the very kind donation. I thank you. Plus everyone who has recently left a lovely review of Murder Mile on your favourite podcast app’, it is hugely appreciated. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED:

On Wednesday 13th March 1940 at 4:30pm, in the Tudor Room of Caxton Hall, Udham Singh would murder Sir Michael O'Dwyer, a man he had never met before, but fuelled by hatred over twenty-one years, Udham’s reason to kill would make him not just a murderer, but a martyr.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of Caxton Hall on 10 Caxton Street is where the bright green triangle near Westminster, just off The Thames. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

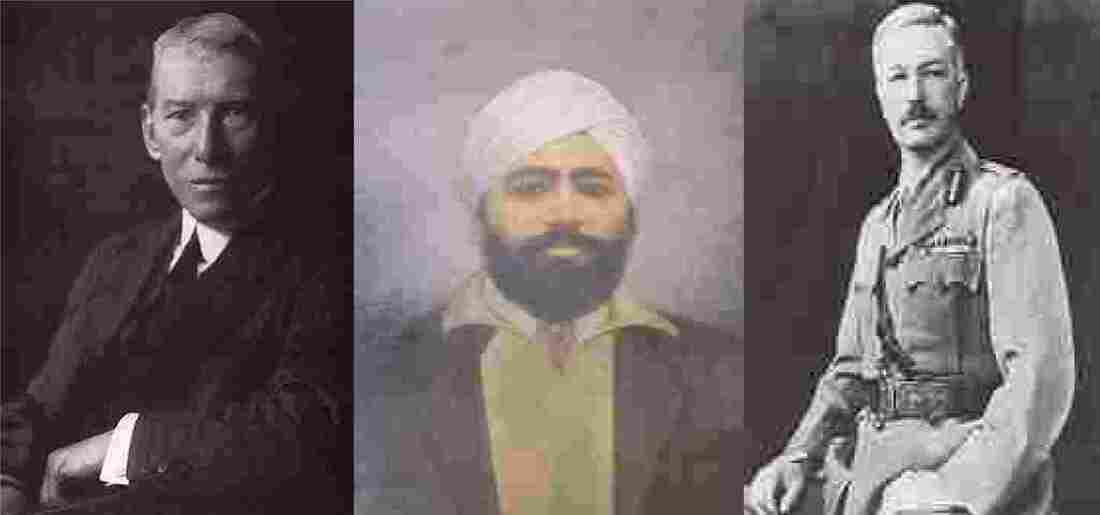

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified police incvestigation files from the National Archives - https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1257785 MUSIC:

SOUNDS: Spent Cartridges - https://freesound.org/people/shelbyshark/sounds/501566/ 22 Rifle - https://freesound.org/people/gezortenplotz/sounds/19514/ Old Time Rifle - https://freesound.org/people/craigsmith/sounds/438581/ Enfield 303 - https://freesound.org/people/kyles/sounds/450854/ Chambered Round - https://freesound.org/people/shelbyshark/sounds/505203/ Sikh Music - https://freesound.org/people/CasaAsiaSons/sounds/240820/ Sikh Celebration - https://freesound.org/people/bangcorrupt/sounds/486622/

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: