|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED:

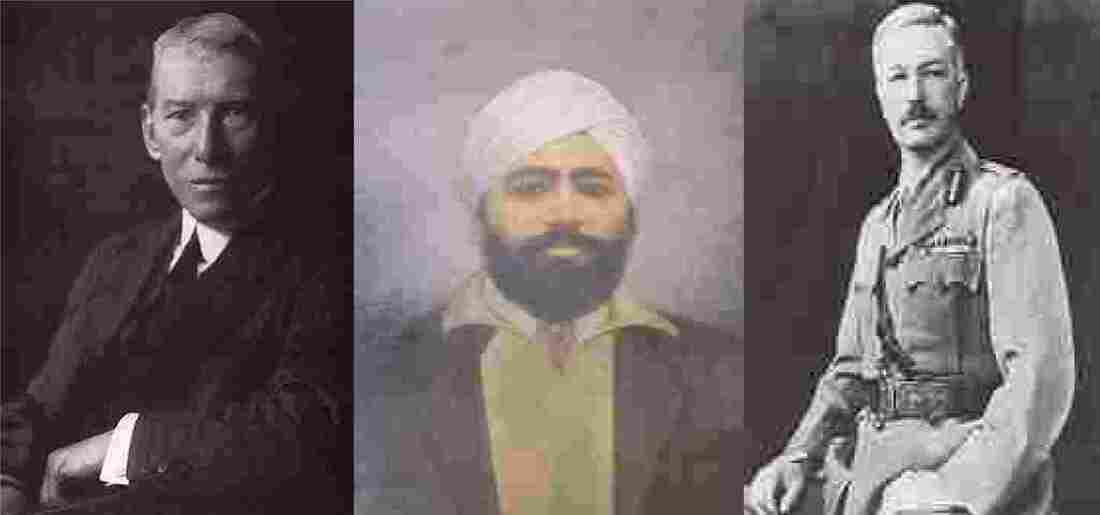

On Wednesday 13th March 1940 at 4:30pm, in the Tudor Room of Caxton Hall, Udham Singh would murder Sir Michael O'Dwyer, a man he had never met before, but fuelled by hatred over twenty-one years, Udham’s reason to kill would make him not just a murderer, but a martyr.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of Caxton Hall on 10 Caxton Street is where the bright green triangle near Westminster, just off The Thames. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified police incvestigation files from the National Archives - https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1257785 MUSIC:

SOUNDS: Spent Cartridges - https://freesound.org/people/shelbyshark/sounds/501566/ 22 Rifle - https://freesound.org/people/gezortenplotz/sounds/19514/ Old Time Rifle - https://freesound.org/people/craigsmith/sounds/438581/ Enfield 303 - https://freesound.org/people/kyles/sounds/450854/ Chambered Round - https://freesound.org/people/shelbyshark/sounds/505203/ Sikh Music - https://freesound.org/people/CasaAsiaSons/sounds/240820/ Sikh Celebration - https://freesound.org/people/bangcorrupt/sounds/486622/

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE:

SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about the assassination Sir Michael O'Dwyer by Udham Singh; two strangers from very different worlds, who had never met before the day of his death. To many, his murder seemed almost random, and yet Udham’s reason to kill would make him a martyr. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 100: The Martyr and the Massacre. Today I’m standing on Caxton Street, in Westminster, SW1; four streets north of the left luggage kiosk where Patrick Mahon dumped the hacked-up bits of Emily Kaye, three streets west of the mysterious murder house of Lord Lucan, five streets south-west of the infamous Spaghetti House siege and three streets north of the hammer-wielding butler Victor Ford-Lloyd - coming soon to Murder Mile. Westminster is the heart of the British political system, as within spitting distance (a feat tested by so many protestors) is 10 Downing Street, the Foreign Office, the relevant Ministries and the Houses of Parliament; where laws are made, lies are spouted and the same useless toothless morons are made into Ministers, swiftly sacked for being crap and punished by being promoted – and that is democracy. Infamous for its protests, Westminster is often filled with more placards than people, as everybody’s voice has the right to heard… even the idiots. Except recently, when a very astute Police Constable saw five knuckle-scraping skinheads staggering towards the Black Lives Matter protest, and instead of riling them up by suggesting they weren’t welcome, she hit them were it hurts by saying “sorry lads, you can’t bring booze into Parliament Square”. And with that, they toddled off to The Jolly Racist pub, unaware that everything they love (beer, football and curries) was invented by the “bloody forunuz”. Two streets away from Parliament Square is Caxton Street; a small side-street crammed full of new offices, old houses, renovated flats, a single tree and Caxton Hall, a place not of protest, but of debate. Built in 1883, Caxton Hall is a five storey, grade II listed, former town hall with a history as colourful as the red and pink sandstone its sculpted from; having witnessed many musicals, speeches and the weddings of Peter Sellers, Ringo Starr, Elizabeth Taylor and Joan Collins (not to each other), as well as political movements, such as first Pan African Conference, the Women’s Social & Political Union and the first public meeting of the Homosexual Law Reform Society. And although, almost all of these events (except the marriages) ended peacefully, it was also home to a very political murder. As it was here, on Wednesday 13th March 1940, in the Tudor Room, where Udham Singh would come face-to-face with Sir Michael O'Dwyer, for the very first time… and would shoot him dead. (Interstitial) So, what connected the Indian killer and his Irish victim? Well, on the surface… nothing. Michael Francis O'Dwyer was born 28th April 1864 in Barronstown; a remote windswept farmstead in County Tipperary in the south-west of Ireland, four thousand miles from the Punjab in northern India. As the sixth of fourteen siblings to John, an affluent landowner and his wife Margaret; as Irish farmers who had struggled in the wake of the Great Famine which left almost a million people dead - with their country torn between independents and nationalists - the O’Dwyer’s turned their backs on their own homeland to climb the greasy pole of prosperity, having sided with their brutal British oppressors. From an early age, Michael was raised and educated to be British, not Irish. To be cold, ruthless and ambitious. To never give-in or give-up, no matter how unfair, unkind or inhumane his orders or goals. And being an Irish farm boy, his only assured route to success was through the Indian Civil Service. With India under the tyrannical boot of the British Empire, the careers and wealth of many infamous leaders and politicians - whose statues still stand tall on our streets – were forged in India’s blood, as seeing its people as uncivilised savages to subjugated, Michael adopted this attitude of supremacy. In 1884, having passed his Indian Civil Service exam, he was posted as an ICS officer to Shahpur in the Punjab, where – later promoted to the euphemistically titled ‘Director of Land Records’ – he oversaw the resettlement of Indian land to native people and tribes, but mostly British landlords and investors. With a total disrespect and disregard for Indian life, culture and sensitivities, he lived as the British did, with the invaders in privilege and the natives in poverty, their country ravage by colonialism. In 1887, assigned to ‘re-organise’ the separation of the North-West Frontier and the Punjab, after quarter of a century of re-writing laws, rules and boundaries for Westminster, in May 1913, he became Lieutenant Governor with total control over the Punjabi people, for which he would be knighted. Upon his succession, Viceroy Penshurst warned Sir Michael that “the Punjab was highly flammable and (if an explosion was to be avoided) it required careful handling”, a skill he was not blessed with. In 1914, with Britain losing the bloody conflict with Germany, although countless Indians had died in the fight for independence, now the master come crawling to its slaves for help. Under the Defence of India Act of 1915, 360,000 Punjabi men were enlisted to die for their captor’s King and country, in return for land, money and the promise of a better future. It was a promise which was agreed with a metaphorical handshake, only once they had turned, that same hand would stab them in in the back. Being short on soldiers, sensing an uprising of Punjabi nationalism and with the country on the brink of unrest, under “emergency war-time measures”, the Defence of India Act 1915 limited the civil and political liberties of the Indian people, a draconian act strongly favoured and enforced by Sir Michael. But by 1918, with the war over and the “emergency measures” obsolete, as Indian soldiers returned from the battlefield to their homeland with a sense of loss and every promise broken, seeing a rise in radical thought, the British sought to supress India’s freedom, by extending those war-time rules. The Rowlatt Act was passed by the British Government on 10th March 1919, and although Sir Michael wouldn’t be murdered for another twenty-one years, the date is significant, as just five weeks after it was signed, his actions would invoke of the one of the world’s bloodies and most shocking massacres. So, who was Udham Singh and why did he kill? Born on the 26th December 1899, in the impoverished Sangrur district of the Punjab, Udham’s birth name was Sher Singh. With his mother having died in child-birth, he was raised as the second of two sons to Sardar Tehal Singh Jammu, a widowed watchman of a railway crossing in the village of Upalli. Aged three, following the tragic sudden death of his father and with no family to raise two sensitive little boys who had nothing and no-one, Sher and his older brother Mukta were sent to the Central Khalsa Orphanage in Amritsar, where Sher was initiated as a Sikh and given the name of Udham Singh. Of those first two decades of his life, that is all we know; in 1916 he attended Khalsa College, in 1918 he graduated, and in 1919 he left the orphanage. Living under the brutal British boot, with the Rowlatt Act curbing his rights, Udham was conscripted to fight in the Third Anglo Afghan war against the Afghan rebels who would win their independence from the British. He served in Basra, East Africa and after four years’ service, he returned home to India to nothing but broken promises. With ‘killing in cold blood’ outlawed in Sikhism and with murder not a part of his curious heart, Udham wanted to see the world, develop his skills, expand his mind and escape his poverty. So, over the next sixteen years, he would travel far and wide, but the things he had seen would eat away at his soul. Setting sail to Mexico, under the alias of a Costa Rican seaman called Frank Brazil (as Indians weren’t permitted to sail on a US vessel), he lived in California, Chicago, Detroit and New York for several years, as well as France, Belgium, Germany, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Switzerland and Italy, only to earn his passage back to India, in July 1927, by working as a carpenter onboard SS Jalapa. Seeing his besieged country from afar, whilst in the US, Udham had become deeply influenced by the revolutionary nationalist Bhagat Singh, who sought to overthrow India’s colonial oppressors. Upon his return to his birth-place of Amritsar, Udham was arrested for possessing two unlicensed revolvers and a large stash of the prohibited Ghadar Party paper called ‘Ghadr-i-Gunj’, which in Punjabi means ‘Voice of Revolt’. Admitting in court a desire to murder his British oppressors, even though this was his first crime and the only time he had ever killed was in combat, he was sentenced to five years in prison. In 1931, he was released, and after that, everything fell apart. Being under constant surveillance - via Kashmir and East Germany - Udham came to England. For six years, as a committed nationalist, he was literally in the belly of the beast… but his life was in chaos. With no-one to guide him, he was indiscrete about his anti-British attitude; he used several aliases, lodged with known Bolsheviks, and applied for and received travel visas to Holland, Germany, Poland, Austria and Italy, as well as Eastern Europe and Russia, during the rise of Hitler’s fascist dictatorship. Living in a white protestant city, Uhdam wasn’t exactly anonymous; as being an Asian Sikh with a big beard and a bright turban, who drifted from job-to-job, bragged about smuggling arms to India and spouted extremist views, by the end of 1936, having embraced a British way of life, he was cohabiting with a “white woman in the West End” and was making his living as jobbing carpenter and a film extra. By 1938, he was charged with demanding money with menace. By 1939, being unemployed, he was living off benefits of just 17 shillings per week. And by 1940, with World War Two in full force and London ravaged by the blitz, the revolutionary wind had gone out of his sails and he felt like a failure. And yet, his martyrdom was just around the corner. But how? His motivation began more than two decades earlier, in the year that he left the orphanage, as 1919 was a flash point in the collapse of the British Empire and India’s struggle for Independence. With the country crippled by strikes, riots and mutinies, in the five weeks since the Rowlatt Act, seeing Amritsar as a city in revolt, as Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab, Sir Michael had implemented strict draconian rules to maintain his tyrannical strangle-hold on the people and deny them any freedom in their own city; protests were outlawed, leaders were exiled and curfews were brutally enforced. To impose his will and quash any rebellion, the policing of Amritsar was overseen by Acting Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer; a cruel sadistic cold-blooded bully who ruled with an iron rod and no emotion. On Sunday 13th April 1919, given a blank sheet by Sir Michael to enforce the rules at will, General Dyer banned all public meetings of more than four people, and imposed an 8pm curfew starting that night. Only this would be a warning which few locals would heed; as Amritsar was a city of many languages, where few people were literate enough to read the sparsely dispersed leaflets, and - more importantly - it was a key day in the Sikh faith. This was the festival of Baisakhi (Bah-saki); a sacred day where thousands of pilgrim families descend from the hills, to the city, for prayers, food and the cattle fair. Incensed that these peasants had flagrantly ignored his rule on public meetings, at 2pm, General Dyer shut down the cattle fair. But the people didn’t disperse. Instead, with nothing to do and nowhere to go, having already prayed and reluctantly heading home, many drifted aimlessly into Jallianwala Bagh. Jallianwala Bagh, known as the Bagh is a six-acre garden with a twenty-foot well, surrounded by ten-foot high walls and accessed by one entrance and five narrow alleys with lockable steel gates, as during the rainy season, the garden is used for farming, but being flat and arid for the rest of the year, it is also a public meeting place, a Sikh cremation site and somewhere to peacefully protest and debate. At 4pm, estimating the crowd at between 6,000 and 20,000 people, General Dyer did nothing to disperse this crowd, as in his mind, he had already warned them and they had chosen to ignored it. The evening was warm and peaceful, as although densely packed with a small but peaceful protest over two exiled leaders, the Bagh was full of thousands of families playing games, eating picnics and savouring the last few hours of sunlight; the mood was calm, happy and good natured. Only General Dyer didn’t see it that way. This wasn’t a picnic; this was a rebellion, an uprising and a revolt. At 8pm, as decreed, with his curfew in-force and these anarchic peasants deliberately disobeying his direct order, having blocked the main entrance, locked all of the side alley gates and formed a line of ninety Sikh and Gurkha soldiers, armed with .303 Lee–Enfield rifles, General Dyer gave no warning of his bloody intentions, except for his men to “make ready”, “take aim” and “fire”. (Mass shooting) It was like shooting fish in a barrel, as even as the terrified people fled, so thick were the crowds that Dyer ordered his men to fire at the densest part, so each bullet wound penetrate several bodies deep. Panicked, frightened but unable to escape - with nothing to hide behind but a bloody pile of mounting corpses –the fittest were shot climbing the locked gates, the elderly and the sick were crushed in the stampede, mothers died diving into the deep dry well to shield their babies, and with not a single shot being fired back, as the people were unarmed, the troops continued the slaughter for ten whole minutes, manually loading every single one of the 1650 bullets, until their ammunition was spent. With the carnage ceased and the Bagh bathed in blood, Dyer ordered his men to retreat. They didn’t offer any aid, or count the dead, instead with Dyer’s deadly curfew in-force until the morning and the city too terrified to enact a rescue effort, many of the wounded were condemned to lie there, dying. 192 were injured, 379 were dead, the eldest was eighty-two and the youngest was just six-weeks-old. The Amritsar massacre traumatised a nation and having witnessed to one of the worst atrocities ever inflicted by the British, many people were scarred for life. One of whom (it is said) was an 18-year-old boy from Amritsar orphanage, who was serving water at the festival - his name was Udham Singh. To cover his tracks, Sir Michael O’Dwyer initiated martial law in the Punjab on 15th April 1919, two days after the massacre, but backdated the paperwork to 30th March, two weeks before, giving a legal justification for General Dyer’s atrocity. And having re-enforced his side of the story to the British high-command, he sent a telegram to General Dyer saying “your actions were good, right and I approve”. Under the protection of Sir Michael, General Dyer was found innocent of any criminal charges, he was removed from duty, denied a promotion and he retired from the Army on a pension provided by the British people who felt what he had done was right. He died in 1927, unrepentant for the massacre. Arrogant to the end, Sir Michael O’Dwyer was relieved of his office by Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, to which he replied “well, that’s what comes of having a Jew in Whitehall”. He returned to London with his wife and children, to live out a comfortable retirement as a public speaker. Twenty-one years on, with Germany as the new enemy, many had forgotten about the massacre… but one man had not. And although murder was against his religion, Udham Singh still harboured enough hatred to kill. On Wednesday 13th March 1940 at 3pm, in the Tudor Room of Caxton Hall, a meeting of the East India Association and the Royal Central Asian Society was held to debate the conflict in Afghanistan. Hosted by Brigadier-General Sir Percy Sykes, chaired by Lord Dundas (2nd Marques of Zetland and Secretary of State for India) with lectures by such luminaries as Lord Lamington (2nd Baron and former Governor of Bombay), Sir Louis Dane (former Under Secretary for the State of Punjab) and Sir Michael O’Dwyer (former Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab). All were titled, all were white and all were British. Entering via the wooden double-doors of the red and pink sandstone of this former town-hall, Udham Singh was given a wide-birth as he cut through the throng of the white and privileged; as although he wore a dark suit, was clean-shaven and had swapped his turban for a trilby, to many Westerner’s eyes this brown skinned man seemed a strange addition in this discussion of Asian affairs. With his ticket in hand to this sold-out event and ushered into the small but snug wood-panelled room, as all one-hundred and thirty of the rickety wooden chairs were occupied, Udham stood with a small group of late-comers, in a thin aisle to the right of the room, a few feet from the speaker’s platform. Stood slightly behind, Bertha Herring, a self-described spinster from Wraysbury, later stated “I saw a dark coloured man five yards ahead. I wondered who this man was and how he came to be here. He appeared to be of very unpleasant appearance”. Being dressed in a clean white shirt, shiny black shoes and a smart woollen suit with bulges in both jacket pockets, Udham shrugged-off this racism, as her bigotry simply set the tone of the afternoon and besides, given what needed to do, he needed space. At 3pm, the lectures began, with a dull Anglo-centric diatribe by Lord Zetland; who exalted the British, vilified the Afghans and reminded the room of how “we know what’s best for them and their kind”. And although his crass comments were well-received with a polite applause, he wasn’t why the people were her. As the next speaker was Sir Michael O’Dwyer. Two decades on, this seventy-five-year-old former Governor of the Punjab was thin, grey and frail but fervently unrepentant for his past. In a twenty-minute speech, delivered in his notoriously “racy Irish manner” and littered with the kind of unabashed bigotry, lazy stereotypes and hate-filled xenophobia which (today) would end a career, Sir Michael was cheered and harrumphed as he frivolously joked about the Afghan invasion of India and his crushing of the Punjabi uprising – a tyrannical action for which he was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Empire – whilst he conveniently side-stepped the tricky topic of the hundreds of unarmed civilians slaughtered, under his orders, at the Amritsar Massacre. As Sir Michael concluded his racist rant to a rapturous applause, a standing ovation and then took his seat on the right of the stage, although barely inches away from his would-be killer, through it all, Udham had remained stoic and remarkably calm. So calm, that he listened to the rest of the lectures. At 4:30pm exactly, as the meeting was concluded by Lord Lamington - and the densely-packed room echoed to the familiar hubbub of dying applause, appreciative murmurs, the shuffle of papers and the creak of wooden chairs as the audience slowly filed out and the speakers on stage all congratulated each other on how marvellous they were – clutching a British issue Smith & Wesson .455 calibre six-round revolver, Udham dashed forward and (from just eighteen inches away) he fired six quick shots. Caught off-guard by the gun’s sharp recoil, his last four shots missed their mark – as one nicked Lord Lamington’s right wrist, one grazed Sir Louis Dane’s forearm, one caused a superficial abrasion to Lord Zetland’s left lower ribs and one missed the stage entirely – but his first two shots were bang on target. Fired into Sir Michael’s back, the second bullet smashed through his 12th rib, his right kidney, his stomach and came to rest inside the front of his crisp white shirt. The first smashed his 10th rib, ripped through his right lung, the right ventricle of his heart and exploded out of the left of his chest. Unlike those who had been murdered at the Amritsar Massacre; his killing was by one man, not ninety; his injuries were caused by two bullets, not an exhaustive wall of shredding lead; and his death would be quick, not a ten-minute terrifying slaughter, followed by a long night of pain, tears and fear. Instead, he staggered, he collapsed and he died almost instantly; with no time to feel pain, to ask why, to face his killer, to apologise, or even to regret his decisions which sent countless thousands to an early grave. As the room erupted into panic, a stampede of screaming people tumbled over chairs and formed a bottle-neck by the only exit. Before Udham could reload or escape, having shouted to her sister to “bar the exit”, Bertha Herring had blocked the packed aisle, later stating “I did nothing. I merely put my fat body in the way to stop him”, and as Mr Wyndham Riches threw a coat over Udham’s head and wrestled him to the floor, although the assassination had descended to the depths of an old-fashioned farce, Udham Singh, the Indian Nationalist had surrendered, as his mission was finally complete. (End) Smiling and composed, Udham was arrested moments later. In his pocket, they found a linoleum knife, a box of twenty-five rounds, two French Francs, sixty Russian Roubles and a small red diary in which he had written the addresses of Lord Willingdon, the Marquez of Zetland, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, and in that day’s entry, it read - “3pm, Caxton Hall” and “Action. Only the way to open the door”. Under the alias of ‘Ram Mohammad Singh Azad’, a name which represented the three major religions of the Punjab and his anti-colonial views, Udham Singh was tried at the Old Bailey on Monday 3rd June 1940. After a two-day trial, being found guilty of murder, Mr Justice Atkinson sentenced him to death. Judged by his colonial masters and asked if he had anything to say, Udham made his protest, as angrily thumping the dock, he shouted about the brutality, the slavery, the indecency and the legalised murder of men, women and children, under the so-called flag of democracy and a civilisation drenched in blood. And as he was led away into the cells, cursing “down with British Imperialism, down with the dirty British dogs”, the Judge directed the press not to report a single word that Udham had spoken. With his appeal dismissed, on Tuesday 30th July 1940 at 9am, forty-year-old Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville Prison, having befallen the same fate as any common killer, traitor or spy, which to the British he was. But to the Indian people, he was hailed as a hero. Posthumously, the humble carpenter and orphaned boy from Amritsar was honoured by the Indian people, the Punjabi press and Indian Prime Minister Nehru, who praised his selfless action by stating “he kissed the noose so that we may be free”. Udham was awarded the title of Shaheed (which means "the great martyr"), a district in the Punjab was named in his honour, and just seven year’s after his death, with the British Empire little more than a crumbling ruin, India had won its independence. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. After the break, I shall yawn for a bit, I shall waffle about things I’ve done, I’ll make a tea, I’ll do a quiz which I’ll probably ruin, I’ll tell you some things which weren’t in the episode and then I shall stop. Whoopie-do. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Jennifer Cowles, Carol Gavin and Jane Louise Braun. I thank you all. With an extra thank you to Anne-Marie Griffin and Deryck Hughes for the very kind donations. As well as everyone who listens to Murder Mile and writes a lovely review on your favourite podcast app’, as without listeners, Murder Mile is nothing. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|