|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND TWO:

On Friday 20th December 1940, James Forbes McCallum robbed the Coach & Horses public house in Covent Garden; he was a desperate man whose first and only robbery was ill-judged, unplanned and such a catastrophic failure that it ended in death. And yet, when he was arrested, he was so panicked, he gave the Police five plausible alibis. But which alibi was right?

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of The Coach and Horses public house at 42 Wellington Street, WC2 is where the dark blue triangle in Covent Garden is. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

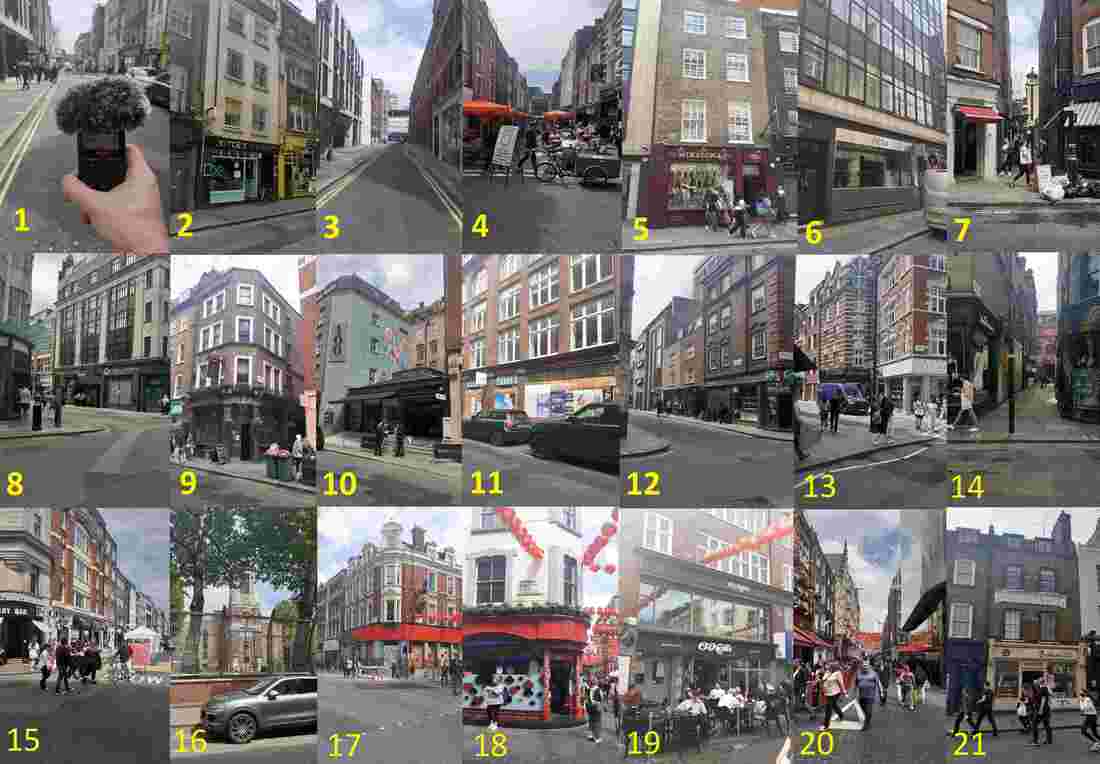

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Left to right; a photo and map of the bombing of 24 Greek Street, 24 Greek as it looks today, 2 Bedford Place (the billet which James & Mac shared and where the gun was left), the Canadian Police HQ at 30 Henrietta Street in Covent Garden and The TRafalgar Hotel on Craven Street.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified police incvestigation files from the National Archives and form the Old Bailey.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE:

SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about James Forbes McCallum, a desperate man whose first and only robbery was ill-judged, unplanned and such a catastrophic failure that it ended in death, and yet, when he was arrested, he was so panicked, he gave the Police five plausible alibis. But which alibi was right? Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 102: The Five Alibis of James Forbes McCallum. Today I’m standing on Wellington Street, in Covent Garden, WC2; one street west of the brutal baker Alexander Moir, two streets north-west of the last days of Mary Ann Moriarty, a short walk from the home of the First Date Killer, and barely one hundred feet south of the former Bow Street Magistrates Court, where an infamous forensic scientist would categorically prove, without a single shred of doubt, that Dr Hawley Crippen had murdered his wife… only he hadn’t - coming soon to Murder Mile. East of Covent Garden is Wellington Street, a thin one-way street from The Strand to Bow Street which is home to the Royal Opera House, the Lyceum theatre and a wide variety of restaurants, cafés, bars and pubs. And although there’s also a museum, being British, the most important places are the pubs. We celebrate everything in pubs, whether births or deaths, commemorations or condolences, week days, weekends or (for those who don’t work hard enough) bank holidays. In fact, if an apocalypse was brewing, the British would probably all head to the pub to drown our sorrows in plop. Like most places, Wellington Street has many watering-holes; some are hideous hipster hovels serving Hoxton’s finest ale in tiny thimbles, some are brewery-owned dumps slopping-out factory produced drinks and nibbles to dull patrons who are allergic to imagination, and some are unashamedly fake boozers, where the décor of Guinness signs, old bikes, potatoes and cheeky leprechauns is so culturally insensitive they might as well have added some burned out cars, kiddie-fiddling priests and insisted that the band wears orange sashes, as the polish bar staff all utter “ta be shar”, as the St Patrick’s Day crowds flock to celebrate a world famous teetotaller by swigging back a mouthful of the “de black stuff”, only to grimace, struggle to swallow and dilute the rest of it with blackcurrant. “Aaah Jayzuz”. Thankfully, at 42 Wellington Street is a real pub. Established in 1753, The Coach & Horse is a staple of Covent Garden life. With its red-fronted facade, greenery above, a left door leading to the public bar and the right door to the saloon, this free-house is authentic, real and hospitable. It’s a great place for a pint, but eighty years ago, it was also the scene of an unplanned robbery and an unexpected murder. As it was here, on Friday 20th December 1940, that a good and decent man called James Forbes McCallum would be driven by a desperate decision to steal money and take a life. (Interstitial). James Forbes McCallum, known to his pals as ‘Jimmy’ was born on 20th Sept 1920 in Dalmuir, Scotland; a few miles north of the bustling ship-yard city of Glasgow. With his father working as a steel riveter- in the docks - being recently married with one boy born and a second soon to join their brood – his mother worked several jobs just to keep a tumbledown tenement over their heads. Known only as ‘Mrs McCallum’, his mother was a short but solid woman made of sturdy Celtic stock, who toiled away from dawn-till-dusk, from job-to-job, with one boy on her knee and one strapped to her chest. For the first few years of his life, James’ whole world revolved around his mother; she was all he would ever see or know. When she wasn’t there he screamed, but when she returned, he was soothed. As a neat and decent woman, seeing poverty as no excuse not to raise her boys well, they always knew their p’s and q’s, their manners and morals, and although she was undoubtably hard-working, she was also a little haughty. Contrasted by her rough callused hands, she wore a fine hat, a neat shawl, she spoke with an upper-class affection, and - to everyone, even her own sons – she was ‘Mrs McCallum’. On 1st December 1922, desperate to flee their grimy Glasgow slum, the McCallum’s set sail to Canada, having arrived in New Brunswick, just three days before Christmas, and set up home in Quebec. As a slightly-sickly intensely-pale child, having taken the bold but wise decision to raise her boys in the crisp fresh Canadian air, although – for the rest of his life – James would always be thin, frail, weak and prone to every cold and infection, his chance of survival was ten times better than in Glasgow. Being an average student, James was decent, likeable but unremarkable, he didn’t excel, but then, he was never in any trouble. And raised well by Mrs McCallum, after school and every weekend, James earned a small wage as an errand boy, half of which he always gave to his mother to earn his keep. In 1931, when James was eleven, his father died, leaving his mother a widower with no income. Being industrious, she turned their home at 391 Third Avenue into a boarding house, aided by her sons. But by his teens, living and working day-and-night alongside such a controlling woman, James felt trapped; he had no future, no fun and – under the harsh scrutiny of his disapproving mother - no girlfriend. Mrs McCallum wasn’t mean, she was just scared, as once her boys had grown-up, she knew she would be left with nothing. In 1938, having become unwell, she shut the boarding house. This was James’ chance to escape, and yet, it was a world-changing event which would provide him with freedom. On 5th September 1939, with Europe at war against the Nazis, eighteen-year-old James did his bit and signed-up to fight as part of Royal Canadian Regiment. Barely passing his medical, as a five-foot eight-inch, skinny and pasty-faced boy who would never see the battlefield, as part of the Canadian Provost Corps, he was assigned to protect London, as the city’s own police force had been decimated. Starting as a Private, within the year he was promoted to Acting Corporal on a wage of $80 a month, $50 of which he sent to his mother in his regular letters. Described by his seniors as a “sober, respected and an excellent officer”, he rarely drank and was never in any trouble. And as a welcome sight, being dressed in the easily Identifiable uniform of the Canadian Provost Corps - a peaked cap with a bright red top and a long grey gratecoat with a bright red emblem – being armed with a .455 calibre Smith & Wesson revolver and based out of nearby 30 Henrietta Street, James and his fellow officers were a familiar and reassuring sight, as they patrolled the streets in and around of Covent Garden market… …just one street from The Coach and Horses pub. James Forbes McCallum was well-mannered, polite and decent; he had a good career, a steady income and a bright future ahead; he didn’t argue or fight, and he had no criminal record or history of violence. And yet, fifteen months after his arrival in England, for the first time ever, in a totally unprovoked and spontaneous attack, he would commit an armed robbery and a homicide. (Interstitial) In a state of panic, as his terrified brain fumbled to find an ounce of logic in his truly abhorrent actions, James give the Police five logical (but equally plausible) alibis as to why he did what he did. Alibi #1 – Drink. Most crimes are committed whilst the culprit is intoxicated, causing a lack of judgment, co-ordination and a misguided confidence. James wasn’t much of a drinker, but in the weeks (and especially in the days) leading up to the incident, his best-friend – 44-year-old Lance Corporal John Osborne, known as ‘Mac’ - said that James had begun drinking heavily, just as he had the night before the robbery. If he was intoxicated, that could explain why his memory is so hazy, why he shouted “hands up! paper money!” but didn’t steal a penny, why he hid his face with a thick woollen balaclava but forgot about his long grey grate-coat emblazoned with a bright red emblem of the Canadian Provost Corps, and – more bafflingly – how James got shot in the arm, when he was the only person in the pub with a gun? And yet, if the barman had fought back (as James would later suggest); why did no-one hear a fight, where were the fingerprints if the barman had wrestled away the weapon, and how could two men have struggled together if there was a bulky set of brass and glass screens between them? That aside, we know that James wasn’t drunk, as – having got his dates wrong - he’d actually drank with Mac two nights earlier, barely drank the night before, and when he was arrested, he was stone cold sober. Alibi #2 – Money. Many crimes are perpetrated for financial gain, as too often, greed and needs can overrule a person’s morals and make even the most sensible do silly and spontaneous things. Sadly, a few weeks after his promotion to Acting Corporal – declared physically unwell – James was demoted to Lance Corporal. If he was broke, that could explain why he robbed the pub, why he felt forced to loan ten shillings off Mac just two days prior, why (as a good boy) he could only send $25 dollars to subsidise his sick mother in November, and why, by 14th December, just one week before, those regular payments would cease. And yet, it seems unlikely, as James wasn’t a greedy man, if anything, he was generous and charitable. Yes, he drank a little heavier, but he wasn’t a drunk or on drugs. And as a Lance Corporal, he still made a good wage, as – with his clothes, food and accommodation all paid for by the military - for the three weeks prior - he was living in a modest double-room at the Trafalgar Hotel, just off Trafalgar Square. Alibi #3 – Illness. As witnessed, thirty-two-years earlier, in the bank of Cartmell & Schlitte, just half a mile west of Covent Garden, a long history of illness and the weakened immune system of a sickly young boy had (possibly) triggered petit-mal seizures - under the grip of which - he robbed a bank, but could recall nothing. Always being pale, weak and frail, having moved from the crisp air of Canada to the chocking smog of London, James’ health had deteriorated. One year prior, having been struck down with pneumonia and pleurisy, the Army doctor had assessed James four times over the last four months – and being declared unfit – he was forced to take unpaid leave, and he was demoted, owing to his poor health. If he was ill, that could explain could explain the robbery, the shooting, the vagueness of the incident without being drunk, and how a good man could be driven to heinously break his own moral codes. And yet, even that seems a stretch, as James had no history of epilepsy nor any mental illness, he was never aggressive, delusional or disorientated. In fact, he was fully conscious of his actions. Being fit to stand trial, he didn’t take the insanity plea and although his memory was a little vague, he pleaded ‘not guilty’ to murder, as he knew the barman, he liked him and the two men had never had any issues. So, the question wasn’t if he had consciously done it. He had. The question was why? Alibi #4 – Trauma. The human body is a marvel of self-repair; skin can heal, blood can clot and bones can mend, but the hardest injury to recover from after an incident isn’t the physical affects but the psychological ones, as although the brain may escape unscathed from an unimaginable horror, trauma can still remain. On Friday 11th October 1940 at 12:35am, three days into the Blitz, a high-explosive bomb hit 24 Greek Street in Soho. It demolished the building, erupted the gas main and trapped dozens in the wreckage. Three people died, eight were injured and countless others escaped unhurt, but were left traumatised by this first brutal wave of bombings from the skies, as innocent civilians (going about their everyday lives) witnessed skin burned, limbs scattered and bodies blown apart, right in front of their eyes. One of those affected was James McCallum. Being psychologically traumatised by the bombing, seeing the Army doctor and complaining of a series of justifiable symptoms – such as tiredness, headaches and nerves - James drank to ease his pain, took sick leave on 16th December, and was recuperating well in quiet of Room 6 in the Trafalgar Hotel. And yet, it was unlikely that his trauma resulted in either the robbery or the murder, as the personality, behaviour, morals and attitude of James had not changed. Those who knew him said, he was still his same old self; quiet, calm, caring, keen to get back to work and was making a slow but steady recovery. Without doubt, all four alibis had (in their own small way) contributed to the crime; money had made him desperate, drink had clouded his judgment, illness had made him weak and trauma had fuelled his fragmented emotions. But these weren’t the main motivations for his crime… …as his fifth alibi was love. Strangely, having first met on the night of Friday 11th October 1940, the bomb which had blasted Greek Street apart had ignited a passion inside a passing couple and driven these two young lovers together. Swept-up in a whirlwind romance - as war-time sweethearts - twenty-one-year-old James McCallum had fallen for nineteen-year-old Irene Turnball, a local waitress and recent orphan. As a perfect match, both were quiet, shy and caring, and just as she was his first love, he was hers. In just nine weeks, they had met, fallen in love, moved into a hotel together and - one week before Christmas - they planned to be married. James had finally met ‘the one’, only there was one obstacle ahead of him… his mother. ‘Mrs McCallum’ would never approve of this girl, or any girl, as no girl would ever be good enough for her little boy, and - as she always feared - once he was gone, this lonely widow would be all alone. On Monday 16th December 1940, having slipped the best ring he could afford onto his beloved’s finger, James and Irene got engaged in the shadow of Trafalgar Square, with their plan to be together forever. On Tuesday 17th, having drank till he was insensible and being in a distressed state, James poured out his woes to Mac – his best-friend and a surrogate father-figure - who he always turned to for help, as - having telegrammed his mother to get her permission to marry - he anxiously awaited her reply. On Wednesday 18th, the day of their wedding, James received a telegram, it read; “Ridiculous idea. Seems very thoughtless towards me. I need your help”, and it was signed “Mrs McCallum”. The young lovers were distraught, their wedding was cancelled and the money they’d saved to marry was gone. On Thursday 19th, with his heart ripped apart by the gut-wrenching decision between disobeying his mother or finally finding love, although Irene was happy to wait, a furious James fired back a telegram to Canada, standing-up and damning her, with a curt “I shall marry, with your permission… or not”. That night, having prematurely signed into the Trafalgar Hotel as Mr & Mrs McCallum, the two timid lovers lay in bed, curled-up in each other’s arms, only James couldn’t rest. After months of illness, days without sleep, still half-hungover, and another night of reawakened trauma as bombers pummelled the West End, having loaned ten shillings off Mac, he knew this wasn’t enough money to get married. At 4am, James left saying he was going to buy some cigarettes. But instead, he did the unthinkable. The Coach & Horses at 42 Wellington Street had long been a family business; owned by Daisy & Harry Phillips, the pub was managed by their nephew David Sholman, with his brother Morris as bar-man. Described as a sweet and kind man, forty-one-year-old Morris, known as ‘Morry’ had only worked in the pub for the last nine months, having lost his job to the war, and although he wasn’t outgoing, the customers liked him, as he was a good man, who loved his wife, his family and kept to himself. Set on the ground-floor of a four-storey red-brick building, most of its regulars would perch with a pint on the pavement, as this small single-roomed pub was barely twenty-foot-deep by twenty-five feet wide. Dominated by a large central bar, the room was split into two; with the larger public bar to the left, and - separated by a partition - a small saloon to the right, which stands twenty people, at a push. And that’s it. With lines of tap-handles for pulling pints, spirit bottles with optics, water jugs as mixers and a tea urn for lightweights, it was a very regular pub. And as a way to serve food and to act as a security measure which kept any drunks from the booze, the bar-staff and the till, above the counter, from waist to head-height, were large brass and glass grilles with a series of spring-loaded windows. Licenced to serve from 5am, having put a £20 float in the till, Morris opened the doors and the day started as it always did… slowly. At 5:10am, fifty-four-year-old John Anderson, a short one-armed lift-operator entered the public bar, ordered a pint and sat reading the paper - he was the only customer. David was in the cellar, Dolly (Morris’s wife) was upstairs and Morris was cleaning the glasses. Less than one minute later, Morris would be dead. As James staggered up Wellington Street, with his mind clouded by equal measures of love and anger and his body stumbling with exhaustion, as this love-sick boy could only see a single solution to his problem – without his mother’s permission - he would be forced to commit his first and only crime. Only, being ill-judged and unplanned, this spontaneous robbery would end in a catastrophic failure. Outside the pub, James’ terrified fingers nervously pulled his woollen balaclava over his pale face. His breathing was fast and frantic, his head was thumping hard, and – having forgotten that his long grey grate-coat was emblazoned with the bright red emblem of the Canadian Police - fumbling his Army-issue revolver in his cold sweaty hands, James dashed into the empty saloon, intent on a quick robbery. Inside, James stammered “hands up! paper money”, only his order didn’t make sense, as with the pub having just opened, the till was full of coins. And yet, amidst the darkness of the sparsely-lit pub, with a bulky brass grille in their way, the two men couldn’t see each other, so although Morris had put his hands up and his eyes shut (in the hope that this would all go away), as James couldn’t tell if he had seen the gun, he swung open the glass of the head-height serving-hatch and poked his gun through. Only, not realising that the window was spring-loaded, the second his left hand let go, it swung back, the glass smacked the muzzle, and flipping his revolver ninety-degrees, James shot himself in the arm. The bungling bandit was dazed, confused and profusely bleeding from a self-inflicted flesh wound. The robbery was a catastrophe and – right then - he should have fled… but with his nerves frayed, his body tense and his hot balaclava riding up his sweat-soaked face, with the eye-holes obscuring any view, he hadn’t realised his mistake and thinking that the unarmed Morris had shot him, James retaliated. A single shot ripped through Morris’ throat, hitting the hard bone of his spine, the bullet then fractured into three pieces – one hit a glass panel, one hit a picture and one hit the tea urn – but the bulk of the lead had severed the barman’s spine, and – before he had even hit the floor – Morris was dead. (End) Being too panicked and traumatised by his actions, James fled empty-handed. Shaken-up, James called Mac, who rushed back to the billet they shared at 2 Bedford Place, and reassured by James that this was nothing serious, he had just “accidentally shot himself, off Covent Garden”, having dressed his wound with a field dressing and iodine, the two pals parted company. Mac went back to their base at nearby Henrietta Street, and James returned to the Trafalgar Hotel and his blushing bride-to-be. At 8am, hearing a bulletin that detectives were seeking a young Canadian Police officer in a long grey greatcoat, with a bullet-wound to his left arm – although they were friends, as Mac was a professional – he called it in. At 9:30am, four hours later, James was arrested for the murder of Morris Sholman. In a state of panic, confusion and exhaustion, being desperate to aid the Police with their investigation, although his memory of this traumatic event was a little hazy, James gave five possible (but equally plausible) alibis to his crime, all of which were back-up by witness statements and irrefutable evidence. Held at Brixton Prison, he was found fit to stand trial. Having refused the insanity plea and (as was his right) pleading ‘not guilty’ to the murder, James Forbes McCallum was tried at The Old Bailey on Tuesday 11th February 1941. After a two-day trial, he was found guilty, he was sentenced to death. On Friday 28th February 1941, a few days before his execution, Mrs McCallum died. Being distraught at the grief of losing his beloved mother, James’ won his appeal on compassionate grounds and owing to the trauma he had suffered in the bombing, and with his execution commuted to life in prison, James was deported back to Canada to serve his time. James Forbes McCallum was denied love by his mother, marriage to his lover, and being short of a few pounds for a very simple wedding, he would be forced to pay the ultimate price. James never married Irene and – being separated by a vast ocean - the two young lovers would never meet ever again. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. That was the episode, and next is Extra Mile, the non-compulsory extra bit which you can choose to listen to, or you can choose not to, I’m good either way, it’s no biggie if you don’t. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Kelly Cook, Caroline King, Neill & Sharon Waugh (happy belated birthday Sharon) and Sioned Jones, I thank you. All of you will be receiving a thank you card full of goodies, and some lucky people will receive very rare Murder Mile key-rings too. Oooh. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|