|

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at The British Podcast Awards, 4th Best True Crime Podcast by The Week, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25.

EPISODE TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY:

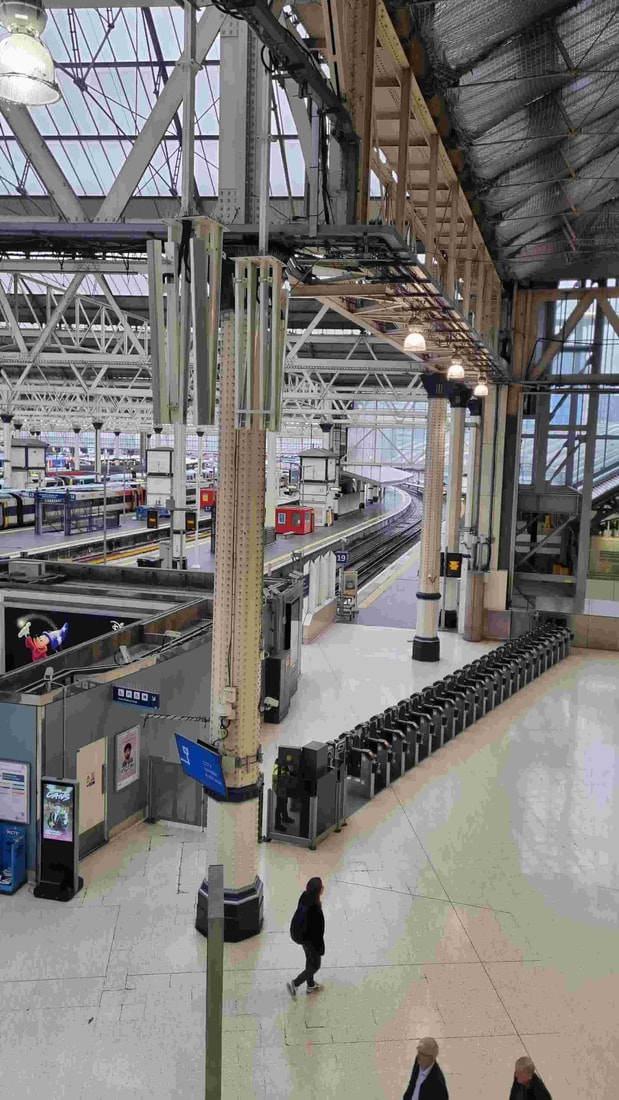

On Monday the 25th of February 1935 at 2:30pm, an unusual parcel arrived at Platform 19 of Waterloo Station. At 21 inches long, 9 inches wide and deep and weighing close to two stone, the train's cleaner found a severed paid of legs. And although to some this was just a piece of lost property, it would lead to one of the strangest criminal investigations in the Met Police’s history.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location is marked with a black coloured exclamation mark (!) near the words 'London Waterlooo'. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other maps, click here.

SOURCES: This case was researched using some of the sources below.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE Welcome to Murder Mile. Today I’m standing in Waterloo Station, SW1; one street south of Peggy Richards’ “fall”, a short walk from the ‘happy slapping’ attack on David Morely, a few feet from the left luggage kiosk where the bloodied bloomers of Emily Beilby Kaye lay, and soon something grim - coming now to Murder Mile. As one of London’s busiest transport hubs, the lost property office at Waterloo Station is a treasure trove of bafflingly bonkers cast-offs which make the cleaners wonder who the hell these weirdos are; having found enough books to fill a branch of Waterstones, walking sticks to stabilise sixty-two wonky centipedes and crinkly-paged grumble mags to milk the saddest git’s love-plums dry. And occasionally, they also find a gimp mask, a llama, a breast implant and (far too often) a stool sample - a human one. But many moons ago, they also found something which sparked a nationwide hunt for a killer. It takes a lot to surprise those who work in this lost property office, and although they still diligently catalogue every object they receive to return each missing item to its rightful owner, what they found back in 1935 would lead to one of the strangest criminal investigations in the Met Police’s history. My name is Michael, I am your tour guide, and this is Murder Mile. Episode 230: Pieces. Usually, at this point in the show, I would introduce you to the victim. With the sad music playing, we would hear about their life, their upbringing, their hopes, their struggles and their dreams, everything from the moment they were born to their last moment alive. But this time, I can’t do that… …I can’t even tell you a few pieces about his life, as that is all that was left of him. Monday 25th February 1935 was bitterly cold, as a Siberian blast had driven London’s winter as low as -28. But in contrast, with highs of 3 degrees and lows of -4, that ice-caked day was practically barmy. The day had begun as it always had, as the train (an electric locomotive with twenty-six carriages) pulled out of a railway siding at Hounslow in West London at exactly 6:48am. Scrubbed and polished by a team of cleaners, the train ran a regular route from Twickenham and Waterloo, stopping at twenty-two stations including Richmond, Mortlake, Barnes, Wandsworth and Clapham Junction. At 1:24pm, the train departed Twickenham Station with hardly a handful of passengers in its first-class coaches, some in the second-class and a smattering in the much cheaper third-class. By all accounts, the journey was uneventful and barring a delay owing to ice, it arrived at Waterloo just shy of 2:30pm. With a light dusting of anonymous passengers disembarking from Platform 19 on the north-west side - all of whom showed their tickets to the inspector – another team of cleaners set about removing any rubbish or lost property from the carriages; maybe some newspapers, some books, and occasionally a pair of missing gloves, a scarf or a woolly hat, although that was unlikely in this bitterly cold weather. A few minutes in, James Albert Eves, one of the cleaners made his way down the third-class carriage numbered 94806, carrying a refuse sack. The train was empty, except for an unidentified man who was dressed in a black suit and hat who – he believed - had boarded for the return leg of the journey. James hadn’t the time to consider the items he’d find and having spotted a brown paper parcel pushed right to the back under the seat - with the biggest crime being to delay the train on its predetermined route back to Twickenham - as it pulled out, James carried the large parcel to the lost property office. Handed to the office supervisor, John George Cooper, both men stared with concern at the parcel. At 21 inches long, 9 inches wide and deep, and weighing close to two stone, wrapped in an odd L-shape, it looked as if it was a fat stubby golf club. Only with its string fraying and the paper wet, James would state “I felt the weight was curious, as at the bottom, when I touched it, it felt like there were toes”. Peeping in through a split, there was no denying what was inside, as John said, “we found legs”. Having alerted the Metropolitan Police, Chief Inspector Donaldson headed up the investigation, aided by Dr Davidson of the Police Laboratory and Sir Bernard Spilsbury as the Home Office pathologist. The brown paper told them nothing, as like the string, it was generic. Unwrapping it, the legs had been swathed in tabloid newspapers; an issue of the Daily Express dated 21st September 1934, six months prior, and two sheets of the News of the World dated 20th January 1935, one month before. But being two of the most popular papers, bloodstains suggested that the dismemberment occurred two days earlier, and with the legs beginning to putrefy, that death had occurred at least eight days before that. Inside were the severed legs of an adult male; complete with shins, calves, ankles and feet, but nothing above the knees. With the lower legs and feet accounting for 12% body mass, weighing roughly 12lbs each, it was clear that he was once a man of 5 foot 8 to 5 foot 10 inches tall, but unable to determine his age – at that point – all they knew was that he was somewhere between 20 to 50 years old. It was impossible to identify him, as he had no scars and no tattoos. Examined at Southwark mortuary, they were able to define his details further, but not much. As being a white pale male, given his fair hair and his freckles, it was assumed that he worked outdoors, and having the musculature of a ‘healthy vigorous male’, x-rays showed no signs of ‘Harris Lines’ (the arrest of bone growth in his teens) or any ‘senile changes’, so it was likely he was in near to his late twenties. But as hard as they tried, the victim couldn’t be identified by his lower legs, and that’s all they had. The wounds told them even less about who had dissected them and why, as with “a clean cut through the soft tissue of the knee joint, just below the patella… it was carried out with extraordinary precision by a person with anatomical knowledge”. But who? A surgeon? A butcher? Or was it just blind luck? And yet, one detail would perplex these officers more than most. With the victim’s toes bent like clenched fists as if to make them smaller, given that his legs were shaved, it suggested that either this man had been so poor that he was forced to wear ill-fitting shoes as hand-me-downs, or he’d been masquerading as a woman. Whoever this man once was, the Police had little to go on… …but they were unwilling to give up. Every passenger who could be traced from the train was questioned, but no-one saw anyone carrying a large parcel or anything strange. But then, how often do we notice other people? And with the parcel deliberately pushed back under the seat, it was hidden, but why would anyone hide a pair of dismembered legs onboard of a train which was heading back to its original location? Had the early morning cleaners at the railway siding missed it by mistake, or had someone planned to dump them? Examining the generic brown paper using infra-red light and microscopic analysis, Dr Olaf Block of the Ilford Photographic Company was able to spot two very faint numbers; a partially erased ‘5’ written in black crayon on the bottom left-hand corner, and a ‘14’ written in pencil in the right-hand corner. Across the city and wider boroughs, Police questioned every courier, freight and removals firms, as they were most likely to mark a parcel with identifying numbers, but it came to nothing. And although this tatty brown paper had been used several times previously, not a single fingerprint was found. The newspapers were submitted to the same scrutiny, as with top-right-hand portion of the front page of the Daily Express having been cut away with a sharp knife or a razor, given that this is where some newsagents tend to write the address of the house where the paperboy should deliver it, the Police spoke to hundreds of vendors, but that cut wasn’t unique enough and the handwriting didn’t match. And although they had enlisted the help of two sculptors from the infamous Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum on Baker Street who made plaster casts of these unusual feet, no-one could identify them. Every piece of evidence had only led to dead ends, and every theory had hit a brick wall. It was suggested that – given how cleanly the legs were dissected – it could have been a prank by a medical student who had removed a pair of amputated limbs from a hospital incinerator. But with the feet being unwashed and the wound devoid of a surgical skin-flap, this theory was quickly discounted. Enquiries were made at hospitals, undertakers and mortuaries whether any body parts were missing, but this turned up nothing. As did the hunt for a butcher or abattoir worker who could have performed such a skilled dissection, “as the knees are particularly hard to disarticulate”, but this too drew a blank. And with the Police appealing for any relatives who were missing a loved one to get in touch, a deluge of families gripped with grief from across the country – regardless of whether their husband, brother or son was a 5 foot 9, fair-haired male in his late 20s, or not – they swamped the phonelines for weeks. So desperate were the Police to solve this case that they had begun to find similarities in the Brighton trunk murders from the year before. But later being dismissed as a theory by Sir Bernard Spilsbury, they were left wondering - why would anyone go to so much effort to disguise the victim’s identity? Or had they? Whether it was a murder or not, they still did not know. Whether he was still alive, they couldn’t tell. And although the Police had some evidence of who this man may have been… …that was all they had – pieces. Three weeks later, on Tuesday 19th March 1935 at about 5:30pm, three boys were playing on the bank of the Hanwell Flight of the Grand Union Canal. As a series of seven locks from the Hanwell Asylum to the River Thames at Brentford, passed a chocking swathe of factories and under two bridges for the Piccadilly Line tube and Southern Railways, Clitheroe Lock was the last before the Great West Road. Having had his tea, 14-year-old Ronald Newman was watching a 70-foot-long cast-iron barge exit the lock, as its weight displaced tonnes of water below it as it slowly headed downstream. But as the wake disturbed the dark calm of the water, “I saw something bobbing up and down”, a little patch of brown as a sack floated on the surface, as underneath a meniscus of mildew, the bulk of its contents dipped. Grabbing a stick, as Ronald drew it near, it was clear that this wasn’t a bag of rubbish, as the sack was as big as a medium sized dog, diamond shaped like a giant stinkbug, and weighed several kilos at least. Heaving with all their might, as the lads wrenched the drenched sack onto the bank, hearing a tearing, they quickly wrestled it ashore as the old rotten sack split. But as Ronald grabbed at its sodden base, as his hand slipped inside the sack, it also slid into a wet festering ooze which stunk like rotting meat. Withdrawing his hand, inside he saw a gaping wound of flesh, and as it slowly dried, within seconds a fever of hungry flies had begun to swarm and feast, at what Ronald knew was “a man’s severed neck”. Having alerted a local Bobby, within the hour, the Met’ Police were on the scene. Untying the string which sealed this hessian sack shut, inside lay a man’s torso; no forearms, no waist, no legs and no head, just a torso. Wearing a tatty brown woollen vest, he hadn’t any of the ordinary clothes a man in his era would wear, no jacket, no shirt nor a tie, just a vest. And with all but the top two buttons missing, and a portion of the lower-left corner having been cut away, it was likely that someone had tried to disguise his identity by removing the laundry marks - but this was just a theory. Having been submerged in the feted water of the canal for several weeks, owing to the decomposition, it was impossible to accurately determine when he had died, or even when he had been disposed of. With his breastbone, every rib and several vertebrae either broken or fractured, with a few ribs poking through the skin like white jagged spears, although the chest had been completely crushed, this wasn’t how he had died as these injuries had all occurred post-mortem, as the cast-iron barges rolled over it. Only this wasn’t an accident, or a body part missing from a morgue, this was undeniably a murder. With no hands nor head found, the erasing of his identity was paramount for the killers, but with the dissection lacking a surgeon or a butcher’s skill, this dismemberment was described as “rather crude”. Lacking the clean slices of a sharpened blade, it was as if someone had been in haste to dispose of this body as quickly as possible, or maybe several men of differing skills had taken it in turns at a side each? Severed at the elbow, the left arm was cleanly cut through the humerus, the radius and the ulna, and where-as the right had been hacked, as a rough jagged knife had ripped the skin and tore at the flesh. With the stomach as crudely ripped as if someone had split a bag of rice, spilling the intestines and its red lumpy guts like a slops bucket at an abattoir, across the top of the hips lay a band of rough tears where the blade had caught and tugged, as a skin flap hung over the innards like a damp cloth cap. And with the neck little more than a fleshy stump severed by blows with a blade and a swung axe, this wasn’t the work of a professional anatomist but a crude killer with a body to disguise. And yet, spotting two wounds to his heart which exactly matched two cuts in the vest, there was no denying… …he had been stabbed to death. The torso told the Police these few facts; as a white male with fair hair, pale skin, freckles and his age initially suspected to be in his 40s to 50s but later determined by x-rays to be in his late 20s, as a well-built broad-shouldered male of roughly 5 foot 9 inches in height, it was likely he was a manual worker. Removed to Brentford mortuary in the grounds of a local gas works, Sir Bernard Spilsbury determined several key details; one, this man was healthy when he died; two, his death was unnatural; and three, there was “a strong presumption” that this torso belonged to the two legs found at Waterloo Station. So, although submersion in water for several weeks had rendered a time of death impossible, based on the legs, it was likely he had been murdered near the 15th February and was dismembered on 23rd. And yet, another unusual detail would pepper this case, as along with his shaved legs and small feet which suggested he was “masquerading as a woman” (a theory which could never be proven), three four-inch-long dark hairs – possibly made from a woman’s real-hair wig – were found on his body. But were they a message, or a mistake? With this stretch of the canal being remote, although questioned, there were no witnesses who had seen anything suspicious, or heard a sack being dumped in the water. But how did he end up here? The Thames Police were requisitioned to drag and drain three miles of the canal, with several hundred yards of it dredged and manually searched, but nothing of significance was found. All barge crews travelling from Coventry to London were interviewed, as well as nomads on the banks, and officials of the Grand Union Canal supplied details about the sluice gates and water flow, but it proved fruitless. One theory as to why the torso was found here was owing to its location, as 200 yards above the lock sits Bridge 206A, which runs the Piccadilly Line train between Boston Manor and Osterley, and 300 yards below sits Bridge 207A, which runs Southern Railway trains from Hounslow to Waterloo Station. The Police mulled over the thought that the torso had been thrown from the train into the canal, and that – maybe - with the severed head and arms tossed into one of several miles of woods or ditches along the train track, and that – maybe - with too many passengers onboard, the killer hadn’t the time to dump the legs before the train reached its destination at Waterloo Station – this was considered. But although the Twickenham to Waterloo train doesn’t pass through Hounslow, and Bridge 207A was downstream from where the body was found, having checked every track siding, nothing was found. That said, the killers could have changed trains, or maybe it was just a coincidence? But with so much evidence leading to this neck of the woods, the Police truly believed that the murderers were local. But who were they, and where were they? With very little to go on, the Police set about tracing the brown woollen vest, hoping that its purchase would lead to the purchaser. Made by Harriot & Coy at a cost of 2 shillings and 6 pence, although this mass-produced vest was distributed to thousands of wholesalers each year, the label was used by one company – a Midlands based garment maker who also sold it to the North of England and Scotland. Every shop which sold the ‘Protector’ brand was questioned, from Bishopsgate to Argyl, Cheapside to Glasgow, but with few records kept of who had purchased this vest, this line of inquiry would stall. As for the sack, with it bearing the name ‘Ogilvie’, a flour manufacturer of Montreal in Canada, when examined, the company confirmed the sack was made in 1929, but was one of 1000s sent to the UK. And although missing persons reports were read for every British county against anyone who matched that description, every lead was checked and proved to be a dead end, and with a less-than-respectable tabloid reporting the discovery of a severed head in Ealing, that was proven to be a lie. With no fingerprints, no teeth, no ID, no laundry marks and no face, his identity was a mystery. Two of the most promising leads they had came in the weeks before the inquest. Continuing the use infra-red rays on the brown paper, Dr Olaf Block had found four words which had been erased – they were “Harry”, “Hanwell” and “Ward 14”. Interviewing the postal clerk at Hanwell Mental Hospital at the back of the Hanwell Flight of the Grand Union Canal, he confirmed the writing was his… but unable to trace who “Harry” was amongst those in “Ward 14”, that clue led to nothing. And the final lead occurred on Monday 25th February at 1pm, 90 minutes before the severed legs were found. At Hounslow Station, Harold Hillier, an attendant saw three men in the booking hall, at their feet lay a large brown-paper parcel. Only one of the men boarded the 1:06pm train to Waterloo, and although he was described as late 20s, medium build and fair-haired, we know he wasn’t the victim. Departing on time, this train didn’t originate in Twickenham, but it did cross the Grand Union Canal at Bridge 207A, downstream of the Clitheroe Lock, where the torso was found. And although the legs were found on a different train, he could have changed at Clapham Junction, or unable to throw them out the window, having arrived at Waterloo Station, maybe he hid them on an outward-bound train? Who these men were nobody knew, but with Harold’s statement backed-up by his colleague Thomas Shea, they confirmed this - that all three men were either Welsh or Irish miners, many of whom were employed locally by McAlpine, who were working on the sewage works and road construction. (End) That clue took the Police one step closer to the victim’s identity. Having questioned Alfred McAlpine, owner of McAlpine Construction, they went through the payroll and employment records for their workers over the last year. But with no-one known to be missing and many of them paid in cash, officers would state “this appeared a most likely clue, but it revealed little hope of success as the firm’s labourers are the flotsam and jetsam of Ireland and Wales”. They had so many clues, but equally as many dead ends and loose threads. On the 10th of April 1935, an inquest was opened at Southwark Mortuary. But with no suspects, no witnesses, no weapon, no fingerprints, and no crime scene to the murder or the dismemberment, on the 6th of June, an ‘open verdict’ would remain into an unknown male torso and a pair of severed legs. Chief Inspector Donaldson would state “every possible enquiry has been made to establish the identity of the victim, but without success. Vigorous but negative efforts have also been made to obtain the identity of the person or persons responsible for this offence”. And with that, the case was closed. Who the victim was will never be known, nor will the resting place of his forearms and head. We don’t know his name, his home or the location of family. We don’t know what he had done, why he was killed, or who by? And denied a proper burial, all that we know of him is all he will ever be… pieces. The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|