|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND THREE:

On Tuesday 4th October 1853, in a squalid first-floor lodging at 6 Little Dean Street, the beating of baby Richard began… and ten days later, he would be dead. Described as a ‘bastard’ child, his widowed mother struggled against insurmountable odds in the hope that he would survive, only those she was forced to trust with his care, became his killers.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of The Coach and Horses public house at 42 Wellington Street, WC2 is where the dark blue triangle in Covent Garden is. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This case was researched using the original declassified court transcripts from the Old Bailey, as well as the British History website, local knowledge, and several news sources from the time. . https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t18531024-name-363&div=t18531024-1123#highlight MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE:

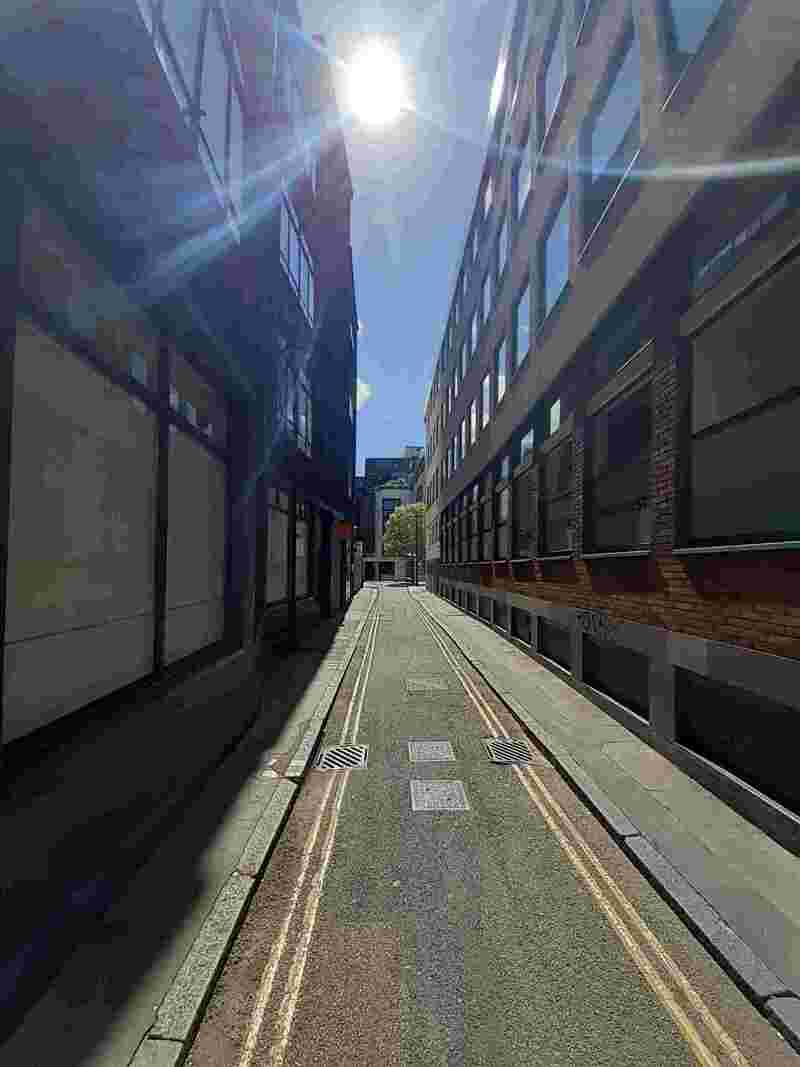

SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about the tragic little life of an eleven-month-old baby boy known only Richard. Described as a ‘bastard’ child, his widowed mother struggled against insurmountable odds in the hope that he would survive, only those she was forced to trust with his care, became his killers. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 103: The Beating of Baby Richard. Today I’m standing on Bourchier Street, in Soho, W1; one road west of the brutal attack on Parisienne sex-worker Jacqueline Birri, several doors down from the sex-shop slayer Richard Rhodes Henley, two hundred feet west of the deaf/mute murder of Rosa O’Neill, and with the rear windows of the Admiral Duncan pub and Dutch Leah’s pad peering over, we are only a one minute walk from The French House where William Raven met his lovers, his robbers and his executioners - coming soon to Murder Mile. Hidden amidst the gloomy darkness of Old Compton Street and Meard Street, Bourchier Street is little more than a side-alley between Dean Street and Wardour Street. First known as Milk Alley; from 1838 until 1937, it became Little Dean Street before being renamed after the late rector of St Anne’s church, and having been demolished three times - once by a bomb - nothing of historical significance remains. Seeing only the backs of four-storey buildings on both sides, Bourchier Street has no houses, no shops, no life nor colour. It’s little more than a series of brick walls, backdoors, fire escapes, gates, a bin store, the locked entrance to an underground car-park, a public relations firm, a set of flats, a single solitary tree (which looks lost) and half of a road which stops dead, smack bang in the middle, for no reason. Being grey, dark, gloomy and drab, it’s only used as a quick cut-through for savvy locals, a hidey-hole where taxi-drivers take sneaky tea-breaks, a little snook where embarrassed skateboarders repeatedly fail to do even the most basic of tricks, a breathing space where editors get high having wasted another day editing shite like ‘Britain’s Wackiest Celebrity Pet Patio Makeovers from Hell’, but - mostly – it’s a place where incontinent men come to piddle having just left the pub and wishing they wore Tenalady. It truly is a pointless part of Soho, a place so forgettable it’s almost as if someone has deliberately tried to erase its past. And maybe they did, as many years ago, when Little Dean Street was an impoverished slum, a desperate woman came here to put her cherished child in the care of another couple. And although, the street, the building and the people have long since been reduced to dust, unable to erase the horror of the crime, some people say that – even today - you can still hear the baby scream. As it was here, on Tuesday 4th October 1853, in a squalid first-floor lodging at 6 Little Dean Street, that the beating of baby Richard began… and ten days later, he would be dead. (Interstitial) Richard was doomed to live a sad and tragic life before his life had even begun… History is primarily concerned with four things; kings, colonies, creations and conquests, almost all of which are the pre-occupation of the prosperous and the privileged, and no matter how little they’re lives have amounted to, their drooling biographers detail the minutia of their frivolously pampered existence in microscopic detail. Where-as the poor and the ordinary? Unless their crime or their death is particularly cruel or grisly, they will only ever be listed a statistic, a footnote or entirely forgotten. Richard’s mother was a nobody, a nothing, a faceless worthless wretch whose name, age and place of birth wasn’t worth the courts recording correctly, so although she was known as Eliza Ryall (possibly the surname of the child’s father), Miss Banks (probably a mistake) and Elizabeth Higgs (supposedly her married name), as her birth name was unknown, all we do know was that Elizabeth Higgs was a middle-aged single-mother with dark ragged hair, pale anaemic skin and a gaunt haunted face. She was tatty, frail and weak, but her look made sense given the stress of her miserable little life. With so much confusion over her names, there are a few possibilities we can assume. If she was born Elizabeth Banks and became Mrs Higgs but was now an unmarried mother called Miss Ryall – with the life expectancy amongst the city’s poor being in the mid-to-late forties – it’s likely she was a widow. Being uneducated, unskilled and recently bereaved, with no known next-of-kin, no home, no savings and no regular income – beyond the meagre money she could scrape-up by toiling away in a series of poorly-paid jobs and being reduced to the shamed indignity of pleading poverty - Eliza was the poorest of the poor, who lived from day-to-day and penny-to-penny, never knowing how long she could last. According to her own account, she has three young children, but as none of them were listed as living in her squalid leaky lodging at 3 Peter Street, the only other option is that (being deemed by the state that she was incapable of raising them alone) all three were condemned to a life in the workhouse; where they would work hard, eat poorly, be beaten, and the odds of their survival was slim. And yet, these were her children who had survived, as this frail widow had three more who had died. Still being only babies, it began as flu-like symptoms; first with tiredness, restlessness and redness of the skin, descending into the agonising swelling of the baby’s body and brain, and gripped by a high fever - as hospitals were not a place for the poor to get well, they were only the sanctuaries for those whose money earned them the right to live – three of Eliza’s babies had died of ‘water on the brain’. On an unrecorded date in November 1852, in the district of Marylebone – being described by the court as a ‘bastard’ (as if his fatherless status meant that rightfully his life should be worth less) - the fourth of Eliza’s surviving children was born and she named him Richard. Being too poor to be baptised, his birth was sparsely recorded and he never received a surname - whether as Banks, Ryall or Higgs. With his birth father absent and the government having enslaved every woman into a marriage merely to survive - as the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1831 penalised and demonised all single mothers to be the sole-breadwinner of their brood of bastards or be condemned to a slow death in the workhouse – this morally self-righteous law had created an unjust system, which was hailed by the law-makers, but was ripe to be abused by cruel people keen to make money out of poor women in a bad way. Earning a pittance, working days and nights, in a series of menial demeaning jobs - where each day Eliza would race across the city to earn a few pennies, only being hired on a ‘first-come first-served’ basis, if she was too late, the job would be gone - so money, food and lodging was never guaranteed. At the start of November 1853, as a mild autumn slunk behind the thick brooding clouds and the sharp winter winds and bitter rains drew in earlier than expected, eleven-month-old Richard caught a cold. He had a little sniffle, a raspy cough and his putty white skin was all warm, red and sticky to the touch. And although his symptoms were mild, as Eliza knew, in 1853, a simple cold could kill. Her baby needed medicine, but without money, Eliza needed to work, but to work - as a single mother - she would be forced to find someone trustworthy but cheap to look after her baby. The young couple she was recommended lived at 6 Little Dean Street, and they were called Mr & Mrs Birch. (Interstitial) On the bitterly cold morning of Tuesday 4th October 1853, at a little after dawn, having wrapped baby Richard in several woollen layers – as still being sniffly, his blue eyes, red nose and pale cheeks were the only features which peeped out of this thick toasty bundle - Eliza left her lodging at 3 Peter Street, crossed over Wardour Street and entered Little Dean Street, a distance of less than one hundred feet. Working seven days-a-week, sixteen hours-a-day, just to afford the basics; food, lodging, a doctor’s fee, medicine and the half-a-crown-a-week the carer would cost, Eliza had to work flat out. But being local – although it ripped her soul apart to be parted for so long from her baby - knowing this was only a temporary measure until he was well and that a good woman would feed him, bathe him and wean him, she could still see her boy two or three times a day, and - when she needed to - she could sleep. As yet another dark and dingy Soho slum, Little Dean Street was a thin airless alley barely one hundred and fifty feet long by five feet wide with two long wooden lines of rickety ramshackle buildings stretching four and five storeys high on both sides. But as each tier overhung – so that every tossed bucket of festering human waste didn’t slop and drip down the window’s below – with barely a crack of skylight above, as both roofs almost touched, the sun rarely (if ever) shone on Little Dean Street. It was leaky, dirty and cold. It was overrun with rodents, over-flowing with effluent, every stair was a death-trap and the back-alley below was a seedy hideaway for gin-swiggers and the sexually depraved, as the feted air hung with the stench of an abattoir, tannery and an open cess pit - and although a rat-infested hovel prone to outbreaks of Typhoid and Cholera was not uncommon - for many, it was home. As planned, part way down Little Dean Street, Eliza knocked at the wooden door of house number six. Greeted by Mrs Birch, she handed the young woman (who she barely knew) a half-crown, a blanket, a woollen shawl, a small sack of food and – as many women would be forced to do - her baby too. That night, just shy of midnight, as a gaunt and haunted woman who was weak with exhaustion having worked from dawn-till-dusk, Eliza made the last of her three trips that day to see her baby boy in the Birch’s first-floor back-room lodging. She cradled him, she breast-fed him, she put him to bed, and she stumbled the short walk home back to Peter Street, for a few scant and anxious hours of sleep. Eliza’s day was as ordinary as many other working-class women in that era who had been forced into a very desperate situation simply to ensure the safety and the future of their families. By chance, putting trust in a stranger, Eliza had sealed her baby’s fate, and ten days later, Richard would be dead. In the ensuing trial into the death of a “bastard child” known only as Richard, as was common practice, Mr & Mrs Birch were permitted to face, question and interrogate their accuser – Miss Elizabeth Higgs – a mother still in grief as nature cruelly continued producing her dead baby’s milk in her aching breast. During the trial, many details would emerge, some were expected, others would be truly horrifying. Going under the seemingly respectable guise of Mr & Mrs Birch, neither were married and both were born liars. Described as ‘dirty-looking’, twenty-two-year-old Joseph Birch was a thief, a layabout and an abusive drunk with a fiery temper, spawned from a close but dishonest family of petty crooks. With a nine-month-old bastard of their own to feed, his girlfriend Caroline Nash claimed to be a carer, but lacking patience and cursed by a cruel and nasty streak, she was less of a mother, more of a monster. Earning a paltry fee, Caroline couldn’t care a hoot for some other woman’s sprog, let alone her own who was left to lie in his own filth, crying and sore, as she’d scream “shut up” and “be quiet” whenever it wailed. And yet, when Eliza was due, pretending to be all sweetness and cuddles, both babies were miraculously calm, quiet and a little bit sleepy, as their milk had been laced with a large slug of rum. So, by the end of the first night, as an exhausted Eliza fed her baby in the dark of the Birch’s backroom - although this clammy tot still wheezed and sneezed - as she put him to sleep, she was reassured as her little boy soundly slept… but his silence would bely the abuse that this helpless baby would suffer. On Wednesday 5th October, as the first of two visits this determined but drained woman could make that day - with three dead babies plaguing her thoughts and seeing similar symptoms return – in those few precious moments that her work would allow, she was focussed on keeping him fed, warm and soothed, so (as far as we know) she was unaware of what had and would happen to her baby. At two o’clock in the afternoon, although it always echoed with the hubbub of everyday life - a shout, a scream, a laugh and a cry - inside the wooden walls of 6 Little Dean Street, the familiar pained wailing of this feverish and restless boy had grown more even heart-rending, as the viscous scorn of two unfit adults (“shut up”, “bloody child”, “little devil”) did nothing to soothe or stifle his screams as Caroline & Joseph repeatedly slapped, smacked and beat Eliza’s helpless baby boy. From across the landing, fellow lodger and mother-of-three Ann Dakin shouted "for God's sake, don't beat the baby so", only to bruskly feel the hot lash of Caroline’s curt tongue, as she barked back “I will do as I see fit” and threatened “shut it, or I’ll hurl you down the stairs and snap your bloody neck”. All of which were backed-up by the drunken brutal bulk of a slurring bottle-swigging Joseph who kicked open Ann’s door and unleashed a volley of holy abuse, as she shielded her babies. And although Ann did threaten to call for a constable - fearing for her life - she didn’t. In fact, no-one said a word; not to the Police, the landlord, or even to Eliza. Moments later, the baby’s screams were smothered. Just shy of midnight, as an exhausted Eliza fed her subdued child – with his wheezing deep, his little chest rattling and his pallid skin all hot and blotchy – sensing the kind of fever which had already stolen half her brood, Eliza only saw the symptoms she feared the most, and not the obvious signs of abuse. In court, with the cruel couple’s litany of lies backed-up by his dishonest family, Joseph dismissed this beating as being just a few light pats on the bottom, Caroline claimed that when the baby came into her care that it was sicker than it actually was (saying “he was almost at death’s door”), and with her boyfriend’s next-of-kin concocting an alibi that neither Caroline nor Joseph were there that night, or any of the subsequent nights when similar beatings took place, often it was their word against Eliza’s. Twice that week, Eliza had taken Richard to see a doctor, and although this professional’s fee for five minutes of prodding was more than she earned in two days’ work, as the diagnosis was uncertain, the wheezing boy was given a mild decongestant and Eliza was told to bring him back if he got any worse. On the odd nights she had him home; sporadically sleeping, always screaming and with his mottled skin a vivid mix of reds, purples and blacks - as the common curse of bed-sores, lice and fleas nibbled at his flesh and as a spiking fever inflamed his swollen blotchy torso - even the doctor didn’t see the bruises, and so – crippled by the expense of doing her best - she returned her baby to Mr & Mrs Birch. Every day eleven-month-old baby Richard would cry, and every day the Birch’s would beat him… On Friday 7th October, at roughly 4pm, just three days into their care, two lodgers at 6 Little Dean Street would witness the abuse - Ann Dakin who lived opposite and Lydia Armstrong one floor above. Within the hard echoey confines of the tiny first-floor backroom, every sound echoed; from the baby’s cries, to the couple’s viscous screams, to the hard slaps as rough hands smacked soft bare flesh as the little boy endlessly cried until it could cry no more. By now, through threats and fear, the whole house had reluctantly become accustomed to its tears, but what Lydia would see next was truly awful. Having pulled a pitcher of water from the communal drum in the basement, as Lydia slowly crept back up the creaky stairs – for fear of incurring the Birch’s wrath – hearing its pained screams muffled for an interminably long time, only to cut the air as sharp and loud as ever (as if the little boy was fighting for his life), as Caroline screamed “it won’t silence, make it quit” and a furious drunken Joseph barked at the boy “you little bastard, I am the master of you”, Lydia peeped through a small crack in the wall. Inside their pitiful little lodging, she witnessed Joseph; his brown toothy shards all bared, his reddened glassy eyes all glared, his heaving brutal bulk towering tall as the tiny wailing tot cowered between his feet on the rough splintered floor. Yanking up the terrified boy by its thin pale arms like it was a rag-doll, being gripped in his hairy fist, Joseph smacked the little boy’s soft head against the hard-wooden skirting-board, a total of eight times, smashing his skull down again, and again, and again, and again, and again, and again, and again and again, until having cast him aside, the little boy lay limp and silent. Once more, nobody did anything or said anything to Eliza or the Police. Joseph denied he was there that night “I was at my brother’s in Borough Road”, Caroline pleaded ignorance “I never touched it, not once. I love my baby I do”, and their family swearing in court and on the Bible that both were elsewhere at the time of each beating… (add “we was at the theatre”, “he was helping me out down the market”, “our mother can vouch so he was”)… as all the while, baby Richard got sicker and weaker. On Saturday 8th October – as Eliza had eaten less to afford more, only to earn less as her work slowed - during one of her brief visits, whilst washing her wheezing boy, the fatigued woman thought she saw bruises on the mottled swollen skin of his skull. Paying more than she could afford for a doctor to dismiss this as abuse and state the obvious - “babies do fall” - seeing all of the symptoms she dreaded in her little boy – aches, swelling, limpness, sweating, shivers and a high fever – just as she had with her three dead babies before him, Eliza suspected that baby Richard had a swelling on the brain… …and he did. Only this fatal swelling of the brain wasn’t caused by a fever, but by his carers. And with his frail little body too weak to fight off his injuries, as his broken mother was tossed back into the viscous circle of an unjust system from which she would never escape - in order to work, to earn, to (barely) live, and (if she was lucky) to survive - she was forced to return her baby back to the Birch’s. In court, the Birch’s and their deceitful kin trotted-out an endless sluice of excuses to provide alibis for Joseph & Caroline’s crimes on the days in question. On Monday 10th, Joseph said “I were in Borough market, my brother’s a costermonger, I was pushing his barrow cos of his bad foot”, with George Birch affirming under oath “that’s true, he didn’t leave till gone nine”. On Tuesday 11th, their excuses were much the same. And on Wednesday 12th, Caroline testified to the court “me and him was at his mum’s all day”, which both parents swore blind was true. Only the lodgers (Lydia and Ann) would tell a very different story to the court, one about the slaps, the smacks and the screams they heard, every single day, at 6 Little Dean Street. But by Thursday 13th, everything would change… At one o’clock, from the first-floor back-room of 6 Little Dean Street, the caustic scorn of Caroline and Joseph was as loud and abusive as ever (“you little devil”, “shut that bastard up”), their slaps were as hard, their wrath was as bitter, and although muffled, the little cries from the baby’s lungs was weak. Being silent and still, suddenly his tiny body tensed, and as a foam of frothy white liquid formed about his lips, with every one of his little muscles trashing violently like he was possessed by a demon, baby Richard was enveloped in a convulsive fit. And for once, Caroline and Joseph’s mouths fell silent. An hour later, Caroline went to 3 Peter Street to tell Eliza that her child was “unwell”. Not dying, not fitting, not beaten to within an inch of its life, just “unwell”. Seeing the silent tot wrapped-up in his cloak with a barely a few pale features visible, she held him in her arms, cradling her limp baby boy. But by the morning, having suffered a second fit, eleven-month-old baby Richard was dead. (End) Grieving the loss of her fourth of seven babies, Eliza viewed her little boy’s cold body in the surgery of Dr Wakem, but even as a layman - having witnessed death by brain fever three times prior - in the stark light of unimaginable loss she could see that his symptoms were not right. With his body cooled, less red and swollen, the mottled bruises to his legs, arms, back and head were unmistakable. A post-mortem confirmed that his bruising was caused by beatings over several days, and – although his symptoms were consistent with a ‘brain fever’ – with no evidence of any diseases except for a cold, the fits and bloody congestion in his brain were attributed to his head being smacked hard against the skirting board. And although he had been a healthy little boy, with his stomach empty, it was clear that the food Eliza had provided, to feed and wean him, Caroline had given to her own boy instead. At the Coroner’s Inquest held at the Globe Tavern in Southwark, Caroline Nash and Joseph Birch were found guilty of manslaughter. Tried at the Old Bailey on the 27th October 1853, for the charge of “slaying a male ‘bastard’ child named Richard”, although Eliza was interrogated by her accusers and condemned as an unfit mother and a liar, she stood her ground and both were found guilty of murder. The life of baby Richard - a bastard whose surname was never determined - was deemed so unworthy that although they should have been executed, Joseph and Caroline were sentenced to just four years in prison. Joseph was sent to HMP Portland in Dorset, Caroline to Brixton Prison, and on their release, they married and moved to Warwickshire, where they had three more children and died in the fifties. Being too poor, baby Richard was buried in an unmarked grave, with several strangers, somewhere in London. And although his mother - Elizabeth Higgs - had done everything she could when faced with a difficult and insurmountable situation where the odds were always stacked against her, sadly being a nobody who meant nothing to no-one, she has vanished from history and her fate is unknown. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. The episode is complete, so feel free to switch off now… but if you’d like to know more details about this case, as well as listen to some meanderingly aimless unscripted waffle about cakes, coots and canal things, please stay tuned for Extra Mile, after the break. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Svetlana Bezverkhaya, Philippa Chapman and Paul Morrissey, I thank you all for your support. And thank you to everyone who continues to listen to the podcast, review it, share it, all the thing that keep it alive. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|