|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

This is a photo taken of the corner of Great Russell Street and Dyott Street where the Rookery and the back of the Horseshoe Brewery once stood, and wher ethe explosion took place.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND FIVE:

On Monday 17th October 1814, at 5:30pm, an iron hoop on a vat of Porter beer at the Horseshoe Brewery would slip, it didn't seem like an emergency, but it would unleash a deadly tidal wave which would change Great Russell Street and the residents of The Rookery forever

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The location of The Horseshoe Brewery is marked with a blood red triangle and is where the words Tottenham Court Road are. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, etc, access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Left to right: the corner of Tottenham Court Road and Great Russell Street where the Horseshoe Brewery once stood, a photo of the Horseshoe Brewery in operation and a photo of the location (post 1920's) after the brewery had closed and the Dominion Theatre was being built.

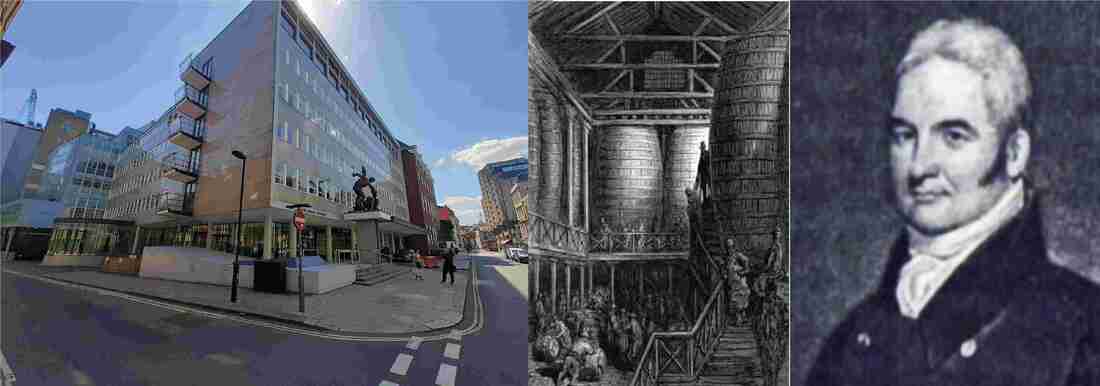

Left to right: the corner of Great Russell Street and Dyott Street (later George Street) where the Rookery once stood and the explosion occured, a drawing of several of the huge vats inside the Horseshoe Brewery, and a picture of Sir Henry Meux.

Left to right: a copy of William Hogarth's Gin Lane (inspired by The Rookery), an example of a building inside the Rookery, a map (with the red lines denoting the Nrewery's boundary, the orange star denoting the point of explosion, and the black lines where the debris was spread) and on the smaller map, the two red stars denote 3 & 4 New Street and 23 Great Russell Street.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This case was researched using the original court documents and many other sources.

SOUNDS: Geyser - https://freesound.org/people/MacFerret_20/sounds/198994/ Water Gushing - https://freesound.org/people/Tomlija/sounds/110103/ Water Gushing 2 - https://freesound.org/people/jakobthiesen/sounds/188427/ Earthquake 1 - https://freesound.org/people/OGsoundFX/sounds/423120/ Cracking Earthquake - https://freesound.org/people/uagadugu/sounds/222521/ Large Earthquake - https://freesound.org/people/LoafDV/sounds/148002/ Earthquake 3 - https://freesound.org/people/zatar/sounds/514381/ Lion Roar - https://freesound.org/people/qubodup/sounds/212764/ Waves - https://freesound.org/people/florianreichelt/sounds/450755/ Bottles Moving - https://freesound.org/people/BeeProductive/sounds/395602/ MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about a tidal wave, a flood, right in the heart of London; a terrifying wall of heavy fast-flowing liquid so fierce it left a trail of death in its wake from Great Russell Street to Tottenham Court Road. Only this wasn’t caused by a river or rain, this very unnatural disaster was man-made. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 105: Meux and the Man-Made Tidal Wave. Today I’m standing on Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury, WC1; two streets north of the forgotten inferno on Denmark Place, one street east of the eatery where Jacques Tratsart massacred his entire family, two streets west of the misreported stabbings on Russell Square, and just a short stone’s throw from the end of the bloody killing spree of Daniel Gonzalez – coming soon to Murder Mile. Great Russell Street is an anonymous little side-street which connects the pricey electronics shops of Tottenham Court Road - where inflation runs riot, logic is lost and the ludicrous cost of every item makes you go “sorry mate, how much?” – all the way to Southampton Row, where hotel prices induce heart-attacks, meals require a mortgage and even a small scoop of ice-cream gets a frosty response. In fact, the only people who walk down this street are lost tourists, having uttered that familiar phrase “excuse please, where is Breeteesh Moozem?”, who vaguely follow my directions of “it’s passed the giant Freddie Mercury, right at the YMCA, down a bit, dodge the crack-addicts and straight ahead”, only to wonder which of the newsagent, car park or burger bar is actually the British Museum. This side of Great Russell Street has a real wealth of very old buildings and very new buildings, with an odd epicentre of modern monstrosities in and around the corner of Dyott Street, which is interspersed with historical gems like diarist Dr Johnson’s house, a tenuous link to Charles Dickens and lots of lovely little Georgian and Edwardian terrace-houses from the 1700’s and 1800’s, and - although Porter was a hugely popular drink – no trace of Meus & Co’s infamous Horseshoe Brewery exists. At present, on this spot, sits an uninspiring piece of brutalist architecture cobbled together from a vague grey mishmash of concrete and glass, known as The Congress Centre; a large conference hall, meeting point and series of office spaces. It is also the home of the TUC (the Trades Union Congress) and USDAW (the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers); two groups who fight hard for better pay, rights, safety and working conditions for every one of Britain’s workers in small or big businesses. Sadly, both were established too late to help the traumatised workers at the Horseshoe Brewery which stood on this site, as a colossal explosion and flood wrecked countless homes and lives, sending many of London’s poorest to an early grave - all caused by a man-made disaster in the pursuit of progress. As it was here, on Monday 17th October 1814, at 5:30pm, that the structural failure of a simple iron hoop would unleash a deadly tidal wave which would change Great Russell Street forever. (Interstitial) It may seem strange to build a brewery in the heart of London’s West End; with the persistent clank of lump-hammers, the bray of dray-horses and a thick sweet cloud of smoky malt belching from the four towering chimney stacks as it billowed down Oxford Street and wafted into Fitzrovia and Soho? But it wasn’t. In Soho alone, there were two breweries (The Lion and Golden) on Broadwick Street, two more (Ayre’s and David’s) on the appropriately-renamed Brewer Street, and on Glasshouse Street, just off Piccadilly Circus, were long lines of factories producing an endless supply of ceramic, pewter and glass drinking vessels for the pubs, clubs and patrons that the breweries supplied. Beer wasn’t illicit, as in the early 1800’s, with no sewer system, drainage and street-side pumps whose water was only fit for washing – as beer was brewed at a high temperature - even children would drink a weak beer for breakfast to keep their bodies hydrated and healthy, they even used it to brush their teeth. In the 1800’s, beer was just an ordinary part of everyday life for men, woman and children. Dating back to 1623, when The Horseshoe was little more than a small tavern, The Horseshoe Brewery opened in 1764 and covered almost a square block; with the length of its yard rubbing against the brick and timber houses on Great Russell Street, the back-yard stretching up to slums of New Street, covering two-thirds of Bainbridge Street and with its ornate steel gates at the junction of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road, it also had a side yard at what later became New Oxford Street. By 1785, as the eleventh largest producer of Porter – a dark malty beer with a nutty smoky taste which is served tepid and is blessed with a long shelf-life - The Horseshoe produced 40,000 barrels of Porter a year. But by 1809, with the site being purchased by the ambitious master-brewer Sir Henry Meux and his partner Charles Young (later of Young’s Brewery), by 1812, Meux & Co became the fifth largest producer in London, brewing 103,000 barrels of Porter a year - a total of 35 million pints. And although this rapid success let him acquire his rival – the Clowes & Co brewery of Bermondsey – Sir Henry knew he was way behind the industry leader, Samuel Whitbread, whose network of breweries churned out a whopping 150,000 barrels, amounting to a staggering fifty million pints of Porter every year. Sir Henry needed to be bigger and better to compete with the competition, or risk being swallowed-up by his rivals. To achieve this, in the preceding years, he followed his father’s successful example. To create this heady full-bodied brew, Meux’s brewery used a large sparklingly clean steam-engine to rhythmically stir barrow-loads of baked malt into a wide drum of boiling water, churning and chugging this super-heated liquid until – through a series of thick lead pipes – it was pumped into a fermentation vat. Porter usually matures for a few months or up-to a year for the best, but to achieve a high volume and keep a consistent flavour and strength, Meux’s Porter was fermented in large wooden vats. Constructed of thick oak pillars, these barrel-shaped vats were often twelve feet wide by twenty-three feet high, holding up-to 18,000 imperial gallons-a-piece and each weighing a colossal 571 tonnes. To keep this heavy and intensely hot liquid from buckling the structure, each gigantic vat was wrapped in a series of twenty-two iron hoops, each weighing seven hundred pounds. Some vats were so tall, they stood three-to-four stories high, higher than the wall along Great Russell and New Street, and standing end-to-end down the three sides of the brewery’s storeroom, stood almost seventy gargantuan vats. The 1800’s was an era of rapid industrialisation, where big business strived to meet the demand of an ever-expanding population and mechanisation had begun to make everything getting bigger, better and faster, but it was only a matter of time until something broke. To many, a failure was inevitable. In fact, it had happened before, and yet – this time - the simple buckling of a single iron hoop on a colossal vat of Porter would unleash on the West End a truly man-made disaster (Interstitial). The real devastation of this technological failure wouldn’t just impact on Sir Henry’s business and his profits, but on the poor wretches forced to live in the dank dark shadow of the Horseshoe brewery. Commonly known as ‘The Rookery’, set across from Soho, this filthy decaying slum sprawled over eight acres of the city’s filthiest and most squalid hovels, from the brewery’s storeroom wall at the back of Great Russell Street to the boundary of St Giles’ Church, in and around where Centrepoint now stands. Dubbed ‘Little Ireland’ or ‘The Holy Land’ owing to an influx of Irish Catholic immigrants, The Rookery was a semi-derelict rabbit’s warren of crumbling tenements, sinister alleys and open cess-pits perched at the precipice of rickety lines of crumbling shacks unfit for human habitation. So squalid, rancid and cramped was this smoky fume-cloaked shanty-town that - on George Street, Bainbridge Street and New Street, a dead-end which backed right up to the wall of the brewery’s storeroom –a single room would often house up-to six families or forty people, and where-as Kensington averaged roughly ten people per acre, The Rookery crammed-in more than two-hundred souls into the same sized space. Packed full of a ragged haggard people, too tired to work, too hungry to sleep and too sick to survive, they lived a life so depressing that hope was nothing but a dream. Crime was rife, sex was cheap, lives were disposable and – to numb the never-ending ache of their bleak little existence – from a nest of seedy brothels and gin-shops, its inhabitants often staggered, high on a lethal mix of homemade hooch - a fizzing stew of potato peel, acid, turps and sometimes urine – as they drank themselves into a slow soporific death. So depressing and debauched was this slum, it was said to be the inspiration for William Hogarth’s infamous painting of Gin Lane. And yet, around it, big business continued to flourish. This was no place to raise a family, and yet, many people had no choice. Bathed in the sunless claggy shadow of the brewery’s twenty-five-foot high walls, spewing chimneys stacks and its towering storerooms stacked high and wide with twenty-three-foot-high fermentation vats of bubbling Porter, The Rookery was dark, dank and dripping in the thick smog of the endless clank of industry. With no light, no fresh air and no sewers, unscrupulous landlords would charge their impoverished tenants for the right to live higher and further off this festering faeces-strewn street. Condemning the poorest of the poor to live at the lowest level, that meant that - when the rains came, the filthy streets were soaked and the cess-pits overflowed - into these crowded basements the sewage always ran. For those in The Rookery, life was hard… but for an unfortunate few, it would also be short. As a faceless people shunned by society and (just-as-quickly) forgotten by history, the only reason we know their names and a few scant details about their lives is because of how tragically they died. Prior to this disaster, which was largely unwritten and yet tallied more deaths than were recorded in the Great Fire of London of 1666, the eight people who perished meant nothing to no-one but those that they loved. And they certainly meant nothing to Sir Henry Meux in whose shadow they struggled. At the Tavistock Arms at 22 Great Russell Street, fourteen-year-old Eleanor Cooper earned a pittance as a servant-girl to keep her family fed. On the first floor of 3 New Street, Elizabeth Smith was carer to four-year-old Hannah Banfield and three-year-old Sarah Bates. And next door, down in the bowels of a dank basement at 4 New Street, aided by Catharine Butler, Mary Mulvey and her three-year-old son Thomas, Anne Saville made the last preparations for an Irish wake, as laid-out before her - draped in a homemade shroud as they were too poor for a pine box - was the body of Anne’s two-year-old son. Unlike a crazed-maniac, disasters are unscrupulously fair, killing the well and the sick, the able and the disabled, the young and the old alike, and often the rich and poor… but not in this case. None of the eight had done anything to deserve to be chosen, and the only reason they were was because they were there. And although this would be their last day alive, for the eight, it was just an ordinary day. Monday 17th October 1814 was an unusual day for a flood, let alone one in the heart of the city. After a long hot summer, with very little rain to feed the crops, to refill the water-wells or to mercifully dampen the stench of more than sixteen hundred unwashed souls in a baking hot slum, thankfully the city was (and still is) sustained by twenty-one hidden rivers – such as the Tyburn, the Kilburn, the Fleet, the Westbourne and the Walbrooke – which ran under the streets, supplying water and a makeshift sewer. But none of them were near a point of flooding and the week’s weather ahead was good. As for a tidal wave, of epic proportions, in the West End? Although the River Thames is fast and tidal, it rarely breaks its banks. When it does, it does so slowly, and being more than a mile south of Soho and with the North Sea a full forty miles away, that day the Embankment would remain dry and a tidal wave so far inland would be unheard of. And yet, it would happen. George Crick had been the storehouse clerk for Meux & Co for the last seventeen years, six since Sir Henry acquired the Horseshoe Brewery and eleven years prior at the Meux’s Griffin Brewery on Liquor Pond Street in Clerkenwell, where even larger fermentation vats were stored. He was loyal, trusted and experienced, so much so that he was able to get his brother (John) a job here as a labourer. Covering almost two acres, the Horseshoe Brewery was the epitome of efficiency with every square metre split into its component parts for the production of Porter; everything from mixing to boiling to pumping to fermenting to bottling to delivery, and fifty foot off the ground, above the storeroom sat a second level for the lead pipes, air-vents and inspection. To the uninitiated, the Horseshoe Brewery was noisy, hot and clammy, but ruthlessly organised with strict systems in place, as any deviation from their tried-and-trusted methods could spoil a vat of Porter, each which cost £40,000-a-piece. At the behest of the owners - Sir Henry and Mr Young - everything was noted, scrutinised and signed-off. At roughly 4:30pm, as George Crick passed the back of the storeroom (that butted-up just eight inches from the wall of the New Street slum), on one of the twenty-three-foot-tall fermentation vats, he had spotted that an iron hoop had slipped. As a professional, he wasn’t concerned and for good reason. Size-wise, the vat wasn’t the biggest. At only ten years it was far from the oldest. And being full of the more mature Porter which had been left to ferment for ten months, being a feisty brew, as its gases build-up, the vat’s lid was prone to blow-off, hence a gap of ten centimetres is left to let it to breathe. Being the third lowest hoop from the bottom of the vat, it wasn’t integral to its structure. As one of twenty-three 700lb iron-hoops which secured the oak-timbers, its slippage wasn’t an emergency. And as the 571-tonne oak vat was prone to expand and contract as it heated and cooled, at least three times-a-year a hoop would slip, only to be repaired or replaced. As part of protocol, George inspected it; the vat’s bottom was level, the sides were stable, there were no leaks of any gases or liquids, and the vat was creaking no more than 18,000 imperial gallons of slowly fermenting Porter should. A few moments later, as part of a formal process, George Crick informed his superior Mr Young, who was also the son of the co-owner Charles Young, that he had discovered a burst hoop. It would take several hours to repair the ironwork, one week to build a new hoop, and to get the wheels of progress moving, George would need to put in a written request to Messers Meux and Young, which he did. And that was it. One of twenty-two iron hoops on a medium sized fully-functional vat had slipped off one of seventy vessels which sat in a well-maintained storeroom with a solid track record in safety. It didn’t creak, crack or rumble. It didn’t split, fizz or shudder. There was no forewarning of what was to happen, no history of incidents where it had, and no clues of the fury which would be unleashed. No-one in the storeroom suspected a thing, as if they had, they would surely have run for their lives? No-one knows that happened. Maybe an oak timber was loose, another hoop was weak, or the 18,000 gallons of warm gassy Porter was unstable? Either way, at roughly 5:30pm, whilst George Crick stood over the storeroom on the overhead platform with a written request for the hoop’s repair in his hand… …the vat shattered. Even in a storeroom as colossal as this, George’s ear-drums popped as the air-pressure peaked and a violent shockwave knocked him off his feet, as the ceiling, walls and floors around him quaked. With its weak point at the rear, having imploded then exploded, it unleashed a force so fierce it was as if a giant fist had crushed the vat like a tin-can; splitting its two-tonne oak timbers like brittle twigs which shot across the brewery like it was under-attack by an army armed with spears, and snapping the 700lb iron hoops like a petulant child with an unwanted birthday bracelet, as thick chunks of sharp shards of hard metal were flung fast, smashed and thudded against the opposing walls. So powerful was the explosion, it demolished a 25-foot-high and two-and-a-half-brick thick wall at the rear of the brewery, toppling several of the four-storey timbers which held up parts of the storehouse roof. In a chain reaction of catastrophe, the vast fast deluge of thick heavy Porter which spewed from the shattered vat like a giant wet wall of terror caused devastation in its wake; knocking-off the stopcock off a neighbouring vat, the force of the blast smashed hogsheads of beer, barrels and casks, flooding the cellar and the storeroom in seconds with almost 300,000 imperial gallons of thick sticky Porter. That’s one million pints of beer or half an Olympic-sized swimming pool which flooded like a fast wall of warm sticky liquid, out of the brewery gates, up Tottenham Court Road and down Oxford Street. Thankfully, having just gone five o’clock, with the brewery reduced to a skeleton crew, only a handful of traumatised workers waded waist-deep in the warm sticky stew calling and searching for those who were missing amongst the shattered casks, floating wood and piles of rubble in a black steaming sea. Thirty minutes later, three men (including George’s brother John) were pulled alive from the ruins and being blessed with only minor injuries, all were taken to hospital, treated and discharged later that day. And although some men made a good recovery, others were unable to ever return to work. Given the colossal scale of the disaster, it was lucky that no-one had died inside the brewery… …but outside in the slum, that was a different story. At roughly 5:30pm, as George Crick stood in the storeroom with the written request in his hand, the weakened vat suddenly shattered. In a volatile explosion, the extreme pressure smashed apart the 25-foot-high, 60-foot-long and 22-inch-thick wall at the rear of the brewery, which led to The Rookery. So explosive was the blast that bricks were thrown two hundred feet away. Mercifully unoccupied, the crumbling slum-houses at 9 and 10 New Street were pummelled to dust as a whirlwind of timber and brick reduced it to rubble, smashing apart two more homes and scattering a thick blanket of debris half way down New Street, so that everything – from the basements to the first and second floors - were strewn with the brewery’s wreckage. Had this accident occurred an hour or two later, when more families were home and the streets and houses were full, this disaster may have claimed many more lives, but the loss would be no less tragic. As the brewery’s brick wall burst, having just sat down to tea in their ground-floor lodging at the back of a shop on 23 Great Russell Street, hearing a cataclysmic crash, the Goodwin family were swept off their seats and spat out into the street by what witnesses described as a fifteen-foot-high “tsunami of Porter”, a thick black wave of ferocity which left them wet, shaken and choking, but thankfully unhurt. Next door, in the back-yard of the Tavistock Arms public house at 22 Great Russell Street, 14-year-old Eleanor Cooper was earning a few pennies to feed her family by washing pots at a water pump at the base of the brick wall, when it collapsed. As hundreds of tonnes of brick and timber rained down upon the young girl, being pinned by timber, Eleanor survived unhurt. But at 8:20pm, although she was still standing upright when they rescued her, having suffocated, there was nothing anyone could do. With half of New Street smashed, flattened and strewn with rubble two-storeys deep, many families lay trapped, only to be dug out hours and even days later. But this debris was their saviour, as with so many basements blocked by bricks, this tsunami of Porter had to go somewhere. Some residents were swept out into the street and some scaled tables to escape to torrent, but others were not so lucky. On the first-floor of 3 New Street, after a gruelling day at work, Mary Banfield was taking tea with her child’s carer – Elizabeth Smith. As the fast flood hit, the thick black wave slammed Mary out of the first-floor window and although she landed broken, bloody and unconscious, she was later found alive, but only just. Sadly, seconds later, as the crumbling structure buckled, its top two floors collapsed and crushed the carer, 3-year-old Sarah Bates and (being trapped) Mary’s 4-year-old daughter Hannah was found drowned in her own bed. And although a horrific sight to witness, the worst was yet to come… As a rabbit’s warren of dead-end streets and tight alleys with no drains or sewers, with her ramshackle lodging at 4 New Street far enough from the blast-zone so only a smattering of rubble had barricaded her door, the full structure was still in-tact, but now, with 18,000 gallons of liquid unleashed, there was no way for her to escape the flood and no way to stop the tsunami. Having finished preparing for the wake, as her two-year-old child lay in state, a tidal wave of thick dark Porter flooded the basement. Later found floating face-down in the cellar, everyone from the boy’s grieving mother to the wake’s three mourners (Catharine Butler, Mary Mulvey and her young son Thomas) had drowned. (End) The aftermath was described as a scene of absolute reverence, as onlookers stood in silence so the rescuers and frantic families could listen out for the cries of loved-ones still trapped amidst the rubble, as right into the night and through to the following day, cartloads of debris and buckets of Porter were cleared by hand. Miraculously, countless numbers of people escaped with their lives and only a dozen needed to be seen by a doctor, but – in total – eight innocent people had lost their lives. And for weeks afterwards, the unforgettable stench of the sticky Porter clung to the street like a painful memory. Out of respect, the brewery’s watchmen charged people a penny to see the smashed vats, and at ‘The Ship’ public house and at the Horseshoe’s yard , the shrouded coffins of the dead lay in state, as long lines of mourners clinked pennies onto a plate which paid for all of the funerals. And although too poor to bury her beloved boy a pine box, finally Anne Saville, this grieving mother had a casket for her dead son (and now herself) as this mother and baby were buried together in St Giles churchyard. On Wednesday 18th October 1814, just two days later, an inquest into the disaster was held at the St Giles Workhouse. Eight people were dead, but with the coroner and jury reassured that this disaster wasn’t an act of negligence but “an act of God”, no criminal charges were brought against the owners, the Horseshoe Brewery returned to business, and Sir Henry Meux was compensated for £30,000 worth of damages and loss he had sustained (almost £1.75 million today). But the families received nothing. As a result of the disaster, oak-timbered vats were phased out, in 1921 the Horseshoe Brewery closed, in 1961 Meux & Co fell into liquidation, and yet, more than two-hundred-years on, there has never been a memorial to those who died; those who were poor, faceless, nameless and forgotten. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. I hope you enjoyed the episode, but if you fancy some extra stuff (which isn’t compulsory) you can stay behind like a naughty school-boy or girl and be forced to listen to Extra Mile, after the break. Before that, a big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are Sheridan Fuller, Lori King and Kelly Garner, I thank you all for your support, it’s much appreciated. A thank you to Darren De-Rosa for your very kind donation, I thank you too. And with a thank you to everyone who continues to listen to the podcast and spreads the word to their pals about how much they love it. That’s hugely appreciated. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER *** The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, therefore mistakes will be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken. It is not a full representation of the case, the people or the investigation in its entirety, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity and drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, therefore it will contain a certain level of bias to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER *** Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|