|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within and beyond the West End.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-SIX:

Today’s episode is about Maria Poulton, a humble cook in a notorious West End tavern called The Coal Hole. Branded as ‘pure evil’, her shocking crime scandalised this infamous den of depravity, only this tragic little murder wasn’t committed through rage or hatred, but mercy and love.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The former location of The Coal Hole Tavern, where Maria Poulton was forced to hide her unwanted pregnancy and the sad truth behind the baby's death is marked with a black cross. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your knowledge of the case. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

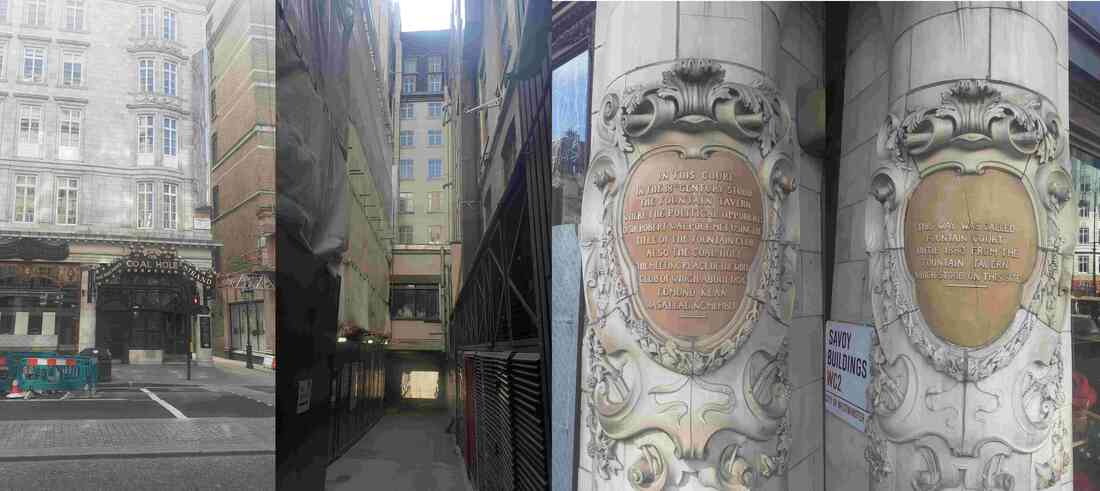

Left to right: The Coal Hole Tavern (at 92 The Strand, not the oriignal tavern, this is the one many people mistake it for), a photo taken inside the alley today (it's the same height and width as in the 1830's) and two photos of the inscription on the pillars at the extrance to Savoy Buildings / Fountain Court.

SOURCES:

This episode is primarily based on the court records from The Old Bailey, as well as many other sources such as census records, newspapers and others.

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about Maria Poulton, a humble cook in a notorious West End tavern called The Coal Hole. Branded as ‘pure evil’, her shocking crime scandalised this infamous den of depravity, only this tragic little murder wasn’t committed through rage or hatred, but mercy and love. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 126: The Coal Hole Concealment. Today I’m standing on the Savoy Buildings, just off The Strand, WC2; one street south of the botched robbery at the Coach & Horses pub, one road north of where baby Harry Hartley was hurled into the icy River Thames, a short walk east of the last 37 seconds of Desmond O’Beirne, and directly opposite The Strand Palace Hotel and the little-known killing of Lila Gillman – coming soon to Murder Mile. Infamous as a semi-prosperous piece on a Monopoly board, The Strand is little more than a four-laned thoroughfare from Trafalgar Square to Temple Bar, passing such thrilling sights as The Savoy Hotel, Charring Cross and the Royal Courts of Justice. It’s a useful place for those awaiting their trial, whereas everyone else simply stands here, looking baffled and asking “how do I get back to Covent Garden?” The Strand is an odd spot to shop, as her mountaineers go gaga over Gortex, preening ponces purr over cashmere pullovers, dullards go “ooh” over a pricy stamps, and – between a mucky-doos for the ne’er-do-wells and a free dose of diabetes at the all-you-can-gorge Pizza Slobatorium – are sandwich shops where throngs of office-workers enthusiastically order “a cray-fish, guava and avocado focaccia”, only to regret nibbling this fishy filth, slide it into a bin and claim “ooh, that was too filling”. One part of this street has always had a specific purpose and although a tavern called The Coal Hole now resides at 91 The Strand, it is often mistaken for its more infamous namesake, a few feet away. Hidden between numbers 103 and 104, and formerly known as Fountain Court, the Savoy Buildings is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it alley leading from The Strand to the River Thames. With no light or life, just walls and doors, it’s little more than a foreboding crack in the city, where behind a series of cellars and corridors, the unseen filth and slog of the hospitality trade is hidden from respectable society. Long since demolished, at 15 and 16 Fountain Court once stood the original Coal Hole. An infamous drinking den, saucy theatre and cess-pit of scandal, where every kind of immoral act took place; some of which were illegal, most of which were depraved, but unfairly, only one was punishable by death. As it was here, on Friday 13th April 1832, whilst perched upon her chamber pot, that a modest cook called Maria Poulton would risk her own life to commit her first and last killing. (Interstitial) By today’s standards, the life of Maria Poulton was far from immoral... ...but back in the early 1800’s, society would regard her as the epitome of sin. Born in 1805, near the Essex hamlet of Ardleigh Heath, Maria was an ordinary working-class girl from very humble beginnings. With no land or home of their own, like so many families forced to toil in the harsh spoils of manual labour - where the privileged stayed pampered and the poor were kept in their place - the Poulton’s fought an everyday battle to be safe, dry and fed. But for Maria life was harder. Blessed with a basic literacy from Sunday school and a good moral code as a Catholic, no matter what her hopes and dreams for her own future were, she was limited to the live the life that the upper-class men of our so-called civilised society had dictated. Therefore, Maria followed her family; with her brothers becoming labourers like their father and her sisters working as domestics like their mother. Physically, Maria was often mistaken chubby, a girl prone to gluttony - with swollen ankles, wide hips and a round belly - but in truth, she was typical of any malnourished urchin who survived on a meagre diet of hard bread, thick lard, starchy potatoes and the cheapest cuts of the fattiest meat. Her face was sickly pale but flushed about the cheeks, and her walk was cautious being crippled by bad joints. As a person, Maria was unremarkable, but what made her so-beloved was her nature. Life had dealt her a dirty hand, but she didn’t let it ruin her day; she knew her place and - with that – she was okay. She was poor but was always clean. She was lonely but not unhappy. She owned little except her pride. And although disadvantaged, throughout her difficulties, she would remain sweet, meek and humble. (Twist) A few years later, she would be branded as a sinner, a harlot and a killer – she was condemned as one of the worst human beings alive - and yet, she didn’t steal, spit or fight, she didn’t even swear. Earning a wage since her earliest years, Maria worked as a maid and a cleaner in the local taverns and later as a kitchen hand. She kept-to-herself, she was rarely ill and she never complained to anyone... ever. Even if her life was bad, she dealt with it, alone. That said, her life could have been a lot worse. So, by late 1820’s, having begun work as a cook at The Coal Hole, although the hours were long; her money was steady, her meals were free, she was warm, well-fed and had a roof over her head - albeit having to sleep in a shared bed with the master’s maid. For a poorly-educated working-class girl, she had done okay; she was single, solitary but self-sufficient. Like many women in this era - with no chance of a pension, savings or a home of her own - the best she could dream of was to marry a good man and spawn several offspring to see her through to her dotage. But by 1831, with her sisters married off and being the grand old age of 26, Maria was cruelly cursed by society as a spinster, and hardly being a great beauty, her family didn’t hold out much hope. Feeling the pinch to follow-suit and (deep down) keen to be loved, in July 1831, Maria met a handsome man called Harris; a romance blossomed, their lust peaked and (just like her love) her belly began to swell... but this love-of-her-life was not-to-be, as being betrothed to another woman, he fled. Maria had been abandoned, left to fend for herself with a little baby growing inside her... ...but being so independent, as a single-mother she could easily have succeeded. Only several months later, her unfortunate circumstance would cause this lovely lady to do the unthinkable (Interstitial) The law has scandalised women, their rights and their biological blessing for centuries. Prior to the 1800’s, the women of England were free from legal or religious persecution regarding the termination of a pregnancy. It was their body and an abortion by any means was their choice. But in 1803, Lord Edward Ellenborough, 1st Baron Ellenborough and Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales sought to legally clarify the term ‘abortion’, the act itself and its punishment. Introduced in the all-male, all white and all devoutly religious House of Lords, after a few amendments (but without the need to consult a woman, or even their own wives), the bill passed the House of Commons (115 years before the first female MP sat in the British Parliament, 165 years before the first female Lord) and it came into law on the 18th May 1803. It took less than eight weeks and opened a viper’s nest of bigotry. Only, this act of parliament - which (in a swift strike) crushed a woman’s right to decide what she could do with her own body and of the life of the unborn baby inside her - wasn’t deemed important enough to establish in its own bill. It was a sub-clause in the Malicious Shooting or Stabbing Act of 1803, which criminalised the discharging of loaded firearms, as well as any stabbing, cutting, wounding, poisoning, maiming, disfiguring and disabling of His Majesty's subjects. Oh, and the termination of pregnancies. As of May 1803, the act decreed it was an offence for any person to perform or cause an abortion post the point of ‘quickening’ (where the foetus can be felt moving in the uterus, usually at 16 to 20 weeks). The punishment of which was either transportation for a minimum of fourteen years... or death. An amendment also criminalised the act of concealment, meaning that should a baby die during the physically dangerous process of child-birth and the mother fail to report it, her innocence may only be found if a medical professional deemed the death an ‘act of God’, but If it had breathed a single breath - in an era where pathology was still in its infancy - the courts could find the mother guilty of murder. Ellenborough’s law penalised all women, especially those who were poor, vulnerable and unmarried. In the 1830’s, by the time that Maria fell pregnant, women were denied the right to vote, own a home or control money. Sex was strictly forbidden outside of wedlock, so if a man chose to ‘seduce’ a woman and subsequently refused to marry her (as Harris did), it was she who would be shamed. Owing to the shame this ‘fallen women’ had brought upon her family, unmarried mothers were often banished from their homes, villages and families – just as Maria had. And with divorce still illegal for another 37 years, if a man grew bored of married life and wanted to marry his mistress, he could declare his wife insane by committing her to the local asylum, where - as ‘his property’ - it was his word against hers. Decreed by Parliament, Maria could be branded a harlot should she record the birth of her illegitimate child, be condemned alongside her baby to a life in the workhouse having been judged an unfit mother simply because she was single, or possibly, convicted as a murderer should she hide its natural death. A few streets away, at the infamous Newgate Prison, an average of 30,000 spectators would leer and jeer, as many bad men were publicly hanged for treason, rape or piracy; many ordinary bods had their necks snapped for such menial crimes as theft, forgery or misrepresenting a will. But often, a woman was subjected to ‘an interminably long strangulation’ having been found guilty of the ‘murder of a bastard child’, a term reserved for child-killers, as well as any mother who had procured an abortion. So popular was this free-entertainment, that opposite the hangman’s gallows was built London’s first drinking fountain, although many of the more ‘respectable’ spectators celebrated at The Coal Hole. Originally called The Unicorn, The Coal Hole Tavern at numbers 15 & 16 comprised of two four-storey red-brick buildings at the north-east end of Fountain Court. As a dark foreboding alley - as gloomy as ashen skin and as skinny as a fleshless bone - with any sun eclipsed by its tall walls, a foul wind whistled down this featureless hole all the way down to the Thames, like a descent into the bowels of hell. So bleak was Fountain Court, that artist William Blake lived at number 3, during his worst depression. Owned by John Rhodes, the Coal Hole was the former coal cellar for the Savoy Hospital. Hidden below ground, it earned a rightfully rude reputation as a place of drunkenness, immorality and debauchery. Only this was not a low-rent flea-pit for grubby labourers and bawdy sailors, this was a high-brow arty establishment for the more discerning ‘young gentlemen’ in their most fashionable top hat and tails. As a member’s club for ‘men-only’, a place patronised by celebrities, The Coal Hole had private rooms for masonic meetings, a lounge where coffee was not the only stimulant, a hotel called the Metropolis where guests could “depend upon well-aired beds” (which was code for ‘sex on tap’), a theatre replete with songs, jokes and a little ‘Tableaux Vivant’ - an arty excuse to ogle the jiggling jollities of a dancer’s boobs, butt and biff – and a tavern where the bawdy excesses of unabashed drunkenness were served in solid silver tankards. And with a blind-eye turned by the law, fights and orgies were not uncommon. Whatever you desired you could have – drink, drugs, sex, flesh – the only rule, you had to be a man. This was not a place for a young lady, but as the cook for its ‘supper club’, Maria saw very little of this. From dawn till dusk, she slaved away in a steamy kitchen, serving honest foods like soups, chops, steaks and pies. She fed the customers and ensured that the master’s small staff were well-fed too. As a cheerful woman with sweet smile and a quiet demeanour, she was neat but never prim-or-proper, she was well-liked and yet rarely said a word, and although senior to Elizabeth Emmerson the char-woman and Sarah Simmons – the maid she shared a bed with – she had a maternal warmth which they both loved. But not being one to freely gossip about her life or loves, they respected her privacy. To those who knew her, there was no denying that, as a quiet, loving and self-sufficient woman, even if her lover hadn’t fled, Maria would unquestionably have been a good mother to her baby... ...only the law-of-the-land would force her to make a desperate choice. For the first few months, she was blissfully oblivious to the baby inside her. But as a reddening flushed her pallid cheeks, her chronic ankles began to swell and a new roundness bulged about her midriff, as autumn turned to winter, extra layers and a thick black apron would disguise her shape, for now. Harris was gone, the scoundrel had fled north it is said, having promised her a ring but he had proposed it to someone else. When she needed them most, her family had turned, having chosen their pride over her life. So now, she had no-one. None of this was her fault, it was fate, but she would be blamed. As her body grew, her options shrank, as every day she was reminded of her dire situation. Outside of The Coal Hole sat The Strand, a busy London thoroughfare; in front, couples passed through Covent Garden, unbothered by the law as a piece of parchment and a gold ring had made them legal; to her left was the Strand workhouse, a stark warning to any unwed woman as its cemetery sprawled with the tiny graves of unwanted babes; and to her right - carried on an ill-wind - were the deathly cheers and cries as yet another ‘evil woman’, an abortionist of a bastard, was hung at the gallows of Newgate. These were the choices she was given... and none of them were good. Living in a top-floor room above The Coal Hole; she had small washing bowl, a dressing table, a thick horsehair bed, and beside this, in a seated wooden box, a porcelain chamber-pot; the precursor to the flushable toilet, where pans of pee and poop were expelled without privacy and disposed of by hand. It wasn’t much, but being warm and dry, she had more than most. And although everything was shared with Sarah, it was cosy, snug and she was good company... but for Maria, it lacked privacy. Changing clothes side-by-side and sleeping belly-to-back, it was impossible to hide such a swollen secret. In court, Sarah would state “I asked, about Christmas-time, if she was in the family way? She said no”, and respecting this modest lady, “I never mentioned it again”. But her pregnancy was very obvious. By that point, being four-to-five months gone and having felt the ‘quickening’, Maria was left with only one option. It was illegal and dangerous, but in private, she would risk her life by aborting the baby. Medically, in the 1800’s, there were very few fool-proof methods to induce an abortion. They all came with risks and they all had side-effects. Some were as mild as cramps and nausea; some were a severe as disability and death. Popular among the poorest were tansy oil, a violent purgative to flush out the bowels; pennyroyal, a herb used for colds, fatigue and as an insect repellent; ergot, an alkaloid to treat migraines, which can cause seizures, organ failure and also miscarriage; as well as cheaper methods like hot baths, turps, street-gin, vaginal plunging, a punch to the gut, or a fall down a flight of stairs. Of course, there was always the sharp tug of a wire-rod by a back-street abortionist, but although more effective than most, their brutal efforts could often be fatal to both the mother and her baby. It is unclear which method Maria chose – maybe one, maybe many – but as a sickly pale girl who was naturally unsteady on her feet, she hid her sickness well, often putting down the vomiting to a bug, or the violent stomach pains to off-food. And as always, as bad as her life got, she dealt with it, alone. Given a little privacy, Maria would perch upon the chamber-pot. Sweating and gripping, as the twinge of hot needles poked her innards, she prayed the poison didn’t kill her, but did its work. And as the debauched excesses of the so-called ‘gentlemen of civilised society’ thundered on, silently she awaited the white porcelain bowl to become flush with the gush of blood and the slop of a limp foetus. There she sat, awaiting her worry to be over... but the blood never came. The abortion had failed, so with baby to be born in secret, Maria would have to deal with the consequences... one way or another. On the night of Thursday 12th April 1832 - with the ‘supper club’ kitchen closed and the nights frivolities winding down – as per usual, Sarah & Maria snuggled-up in bed, their bodies radiated a reassuring warmth. Only that night, Maria was a lot hotter and clammier, and struggling to lie still as she writhed, her rotund frame twisted as she groaned, but when asked, she claimed it was “just a stomach ache”. By the next morning of Friday 13th, having had a fitful sleep, Maria was unusually hard to rouse. Her movement was slow, her pale face dripped with sweat, and unusually, she complained of a headache. She came down to breakfast, which Sarah had prepared, but returned to her bed, her eggs untouched. At 2pm, rightfully concerned, Sarah & Elizabeth returned to the bedroom and softly knocked, but got no reply. They knocked again, but heard nothing. So, as they entered, they saw Maria, alone, perched upon the wooden box of the chamber-pot; struggling to stay upright, her skin wet and her body weak. “Miss Poulton?”, Sarah asked, “what’s wrong?”, the porcelain pot obscured by her long nightdress, a black apron and several petticoats. But in a barely audible whisper Maria replied “nothing... go, please, go”. She didn’t, instead asking “Shall I fetch Dr Jones?”, only Maria said “no, I’m fine”, as she ushered her junior away with the waft of her trembling hand and a feeble attempt at a reassuring smile. Only they knew she was not fine; as her white petticoats were stained red, the floor was dotted with thick spots of blood, and laying about her feet were fistfuls of woollen cloth used to stem the flow. Her lips trembled, as again, sat alone, she was unable to scream in pain, for fear of exposing her secret. Fifteen minutes later, the girls returned. Maria was slumped-over, sitting on the side of the bed; her black apron was gone, her nightdress was untied and its cord was missing. Too exhausted to move, she weakly asked “Elizabeth, please remove this”, pointing to the porcelain pot perched upon the locked wooden box. Its pale white shine stained red, as wadded rags floated in a thick red sea. Elizabeth did so, taking the bloody pot to the side room. Sarah knew but spoke cautiously, “Miss Poulton? Cook? Where is the baby?”. Too tired to talk, Maria uttered “no baby, just had a small miscarriage”, and with no energy left, Maria agreed to see a doctor. The doctor’s aide, Charles Thompson arrived from the surgery at 4 Fountain Court. Bedbound, Maria claimed it was just a stomach ache, but the soiled rags and the spattered pot told a different story. If this was a miscarriage, the law stated that the doctor must observe the foetus, as only he could say whether it had lived or died, even if only for the briefest of moments. Only Maria stuck to her story. As the aide left, rightfully Sarah was worried. The law was the law; he could fetch the doctor, he could tell the master, he could summon an officer. If there was a baby, all three could be charged with aiding the concealment of a baby, so side-by-side with Elizabeth, Sarah asked “please Cook, please show us”. Reluctantly nodding, with a sharp wince, Maria bent down beside the bed. With a click, she unlocked the wooden box which recently held the porcelain pot and pried it open. Inside, all the girls spied was some rags and a black apron. But hidden from sight, as she held a set of scissors, something went snip. In Maria’s hand lay the bloodied cord of her nightdress, hanging limply like two ends of a severed loop, as its once-tight cotton noose has been freed from a vice-like grip. “Oh Cook, tell me you didn’t?”, Sarah pleaded, but Maria had, as wrapped in a black bundle lay a small but well-formed baby girl. Naked and helpless, it lay silent and still, its little face all purple, its tiny tongue protruding and its lips the same blue hue as its eyes, as for both their sakes, she had throttled it before it could utter a sound. “Oh Cook, you... you have hanged the baby", Sarah said. To which, Maria implored her "Hush! Please! You will hang me", but with an officer not far behind, it was too late, her secret was out. (End) In the bedroom, Dr Jones examined the cord and a matching mark on the baby’s neck, which Maria couldn’t account for, stating “I don't know anything about it, I have not done it". But by 7pm, with the arrival of Superintendent Sadler of the Covent Garden police, Maria admitted she was pregnant, unmarried, had hidden her pregnancy and admitted to concealing the baby, but nothing more. That night, 27-year-old Maria Poulton was arrested and charged with murder, but she wasn’t placed in custody. Clearly exhausted and hardly a risk to anyone, they left her to sleep, and each day an officer would check on her wellbeing and when she felt strong enough, she presented herself to the Police. An autopsy confirmed that the baby’s lungs had inflated with air; when it was born, it had breathed, and although much of the evidence of its death pointed to a strangulation by its mother, they could not conclusively confirm whether the baby had died by being asphyxiated by its own umbilical cord. Tried in open court at The Old Bailey on 17th May 1832, Maria was charged with the wilful murder and the concealment of a bastard child, a heinous crime (as despised as treason and rape) which – since an Act of Parliament in 1803 - had warranted a death sentence. Only, now the times had changed, and with the act widely considered an unjust law for many mothers, unwed or not, the judge was lenient. As a woman of good character, praised as mild and meek, Mr Justice Littledale took pity on Maria, dismissed the murder charge and found her guilty only of concealment, she was sent to prison for two years. Strangely, John Rhodes, the owner of The Coal Hole, didn’t sully his name by coming into court. Maria lived out her final days as a domestic servant to a nice family in Clerkenwell; she was 46 years-old, she didn’t marry and - although everyone who knew her agreed she would undeniably have made a good mother - having been forced to do the unthinkable, she never had any children. (End) OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. So, what cake do I have this week? What waffle will spurt out of my blather hole? How long can I last until I grumble out by tea being cold? If you can’t wait to know, and want to learn more about this case, find out after the break. But before that, here’s a promo for a true-crime podcast which may be the epitome of the custard bit in a custard slice. Yum. A big thank you to my new Patreon supporters, who are; Emma Thorpe, Kara Joseph and Sophie Amos, I thank you all, I hope you got your goodies. A thank you to two very kind donations via the supporter link, from MsSuperTech and an anonymous donator, I thank you. Plus a thank you to all new, old and original listeners who continue to share this show with their friends. It’s very much appreciated. But most importantly of all, it’s someone’s birthday. Yes, I’m talking to you Kelly Cook. Yes, that Kelly Cook. You! The great cook, hopefully of cakes. You’ll be delighted to know that a very naughty man you may know called Mattie, has splashed out every single penny he owns (meaning there’s no dosh left to buy a single treat for Snoop or Maisie) and therefore this whole episode is dedicated to you. As a big fan of history, true-crime and horror, I can see why you love Murder Mile so much. So as you’re on your next walk, no doubt doing some serious training to walk an impressive 1000 miles this year – phew, you may even beat me – myself and all the Murder Mile listeners wish you all the very best, and I hope you have a great day and a BIG cake. Obviously. Murder Mile was researched, written and performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|