|

BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian and TalkRadio's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

EPISODE ONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY-NINE:

Today’s episode is about soldiers and sex-workers, two ancient trades intrinsically linked, especially during war-time. And although – if people were created equally – a price would never be put on a person’s life; we clearly value those who fight over those who fuck.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

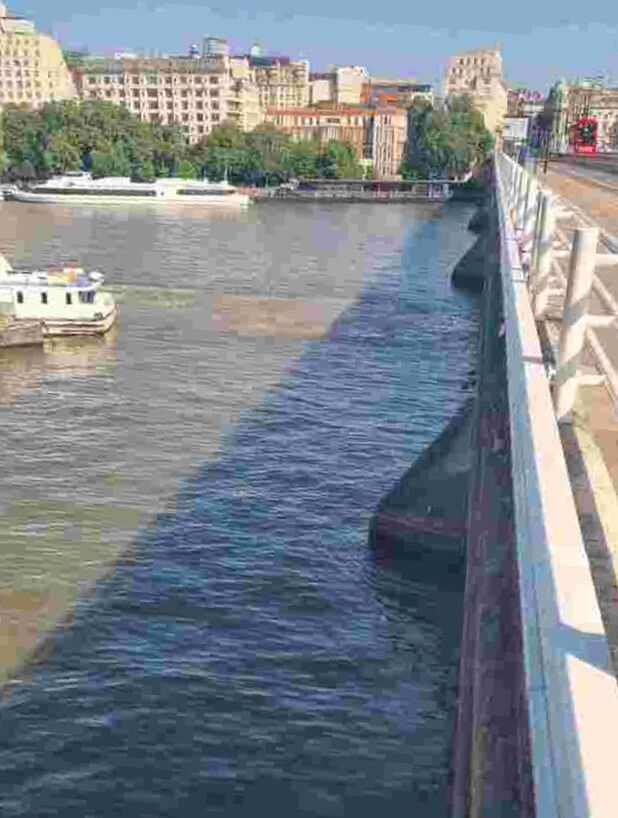

The location of the site at Waterloo Bridge where Peggy Richards fell to her death, having been strangled, is located with a lime green cross at the turn of the River Thames by Waterloo. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, access them by clicking here.

Here's two videos to go with this week's episode; on the left is the exact location where Peggy was (allegedly) strangled and her body dumped over the bridge by Joseph McKinstry, and on the right is the Wellington Hotel on the corner of Alaska Street where Peggy and Joseph drank and had sex. These videos are links to YouTube so they won't eat up your data.

SOURCES:

MUSIC:

UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is about soldiers and sex-workers, two ancient trades intrinsically linked, especially during war-time. And although – if people were created equally – a price would never be put on a person’s life; we clearly value those who fight over those who fuck. Murder Mile is researched using authentic sources. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details. And as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 139: The Fall of Peggy Richards. Today I’m standing on Waterloo Bridge, between WC2 and SE1; one road south-east of the strangled baby of Maria Poulton, two streets south of the botched robbery of James McCallum, a few feet west of David Morley’s assault and close to the drowning of Annie Frimley - coming soon to Murder Mile. Waterloo Bridge (known as New Waterloo Bridge) carries the A301 over the River Thames, between Waterloo on the south bank and The Strand on the north. Fashioned in a box-girder design, it’s made of Portland Stone and is laid over five concrete piles which are sunk into the river’s mud-flats. At 1200 feet long by 80 feet wide, it has four lanes, two cycle ways and two footpaths. Like many of London’s bridges, it’s often ignored as means of connection between the pricey pubs of Covent Garden, the arty-twaddle of Festival Hall, the IMAX where numpties pay twice the price to see the same film (only bigger), a small fortune to go ‘weeee’ on the world’s slowest Ferris wheel, or for footie louts to drunkenly grunt towards Waterloo Station as they tunelessly massacre ever single note. Built as a replacement for John Rennie’s defunct Strand Bridge, New Waterloo Bridge is often referred to as the ‘Ladies Bridge’. Constructed between 1938 and 1945 - with all eligible man enlisted to fight - Lind & Co hired mostly female contractors to complete the work; whether welders, scaffolders or stone-masons. Skilled trades which until the world was plunged into war was only seen as a man’s job. Officially opened in 1945 owing to bomb damage, being the only Thames crossing to be directly hit by German bombers during the blitz, it was partially opened on 11th March 1942, just three weeks after the murder of Deptford sex-worker Peggy Richards. And although, during war-time, women were invaluable to our industries, for those in the “oldest profession”, prostitutes remained invisible. As it was here, on Thursday 19th February 1942, that Peggy Richards would die. But being a potentially political powder-keg between two allied nations, the British legal system would put into sharp contrast who they valued the most; the soldier or the sex-worker? (interstitial) Peggy’s death began as a simple exchange between two strangers... ...one who needed money, and the other who needed sex. Born in 1897, Joseph Ralph Bradley McKinstry was raised in Hull, one of the oldest neighbourhoods of Gatineau, in the city of Quebec, on the south-east edge of Canada. Known to his pals as Buck, Joseph was stockily-built like a swollen testicle, with dark wisps of thinning hair, beady-eyes encircled by a set of silver-framed spectacles and not a single tooth in his head - not one – as adhering to the odd fashion of the 1920’s, he had every tooth ripped out and replaced with dentures to save on dentist fees. In short, Joseph was nothing special. He worked in manual jobs and was often short on cash. He wasn’t much of a looker, but he didn’t struggle when it came to pulling a less-than-choosey lady. And although he wasn’t everyone’s cup-of-tea, some said he was smooth, whereas others called him a cocky twat. In 1923, he was charged with passing false cheques - which seems to be his only conviction, having no known history of violence or assault - a detail which was barely mentioned in any news article. In 1932, he married. But raised in an era when women were seen as little more than an appendage to a man, she is never mentioned by name, only as the ‘wife of Joseph McKinstry’. They moved to Ottawa, set up home, in 1934 they had a daughter called Isabelle, and much later a son called Roland. Many said he was a good father and a loving husband, except morally he had no qualms about spilling his seed in a slew of sex-workers when he was miles from the woman he claimed to love. Again, the press never failed to mention that Peggy was a ‘prostitute’, and yet, they never listed him as a ‘brothel botherer’ or a ‘prossie pest’. Which isn’t surprising, as there are so many derogatory names for sex-workers, but so few for those who use them, as this puts the blame squarely on her, rather than him. With the outbreak of war, as a reservist, 42-year-old Joseph was conscripted into the machine gun re-enforcement unit of the Cameronian Highlanders of Ottawa, an infantry regiment of the Canadian Army. We know this, as the press praised his heroics, but not his inability to keep his penis in his pants. Only, his glorious military career wasn’t exactly the stuff of legend. On 10th May 1940, Private Joseph McKinstry took part in Operation Fork. With Denmark having fallen to Nazi control, Britain feared that the same fate would soon befall the Nordic island nation of Iceland, so (as the British do) they decided to invade and force it to become an allied stronghold. But as military invasions go, it was hardly our greatest hour, as we had grossly under-estimated its peaceful people. Operation Fork was a failure before it began. Fully ladened with guns, bombs and seven hundred and forty-six Royal Marines setting sail for Reykjavik onboard four warships – two destroyers; the Fearless and the Fortune, two cruisers; the Berwick and the Glasgow, as well as 4000 Canadian soldiers, with a battalion of Cameronian Highlanders onboard the Empress of Australia - they were ready for war... ...but with their Supermarine Walrus aircraft flying too low over the port, the surprise was blown. By the time this heavily-armed armada had arrived, the city’s people had filled the dock ready to greet these invaders with smiles and flowers. No shots were fired, no lives were lost and the only upset was the citizens being asked to move back “so our soldiers can get off the destroyer”... which they did. Until April 1941, Iceland was garrisoned by 30,000 bored and lonely troops, some of whom regularly used prostitutes. So much so, that the Icelandic census recorded two-hundred and fifty-five known offspring who were conceived out of liaisons between invading soldiers and Icelandic sex-workers. That year, Private McKinstry and the Cameronian Highlanders were deployed to England, trained at Stirton outside Bradford and later stationed at the Witley Common Camp near Aldershot. And like any other soldier given a few day’s leave, he would head into London’s West End for spirits, sex and sin. In every article, Joseph comes across as a husband, a father and a solider... ...where-as Peggy wasn’t even seen as a person, she was just a prostitute. What details were reported about Peggy were far from glowing. ‘Peggy Richards’ was her street-name, not that anyone cared, and being born Margaret MacArthur near Wallsend in Northumberland about 1910, she died aged 32. And yet, sources would list her age as 34, 38, 42 and even 48, never younger. With twenty-nine convictions for prostitution and theft, they said that she lived a sinful life with an unnamed docker in poverty-strewn Deptford, and – as a sex-worker who spread ‘venereal disease’ for her own selfish need – she was described as “ugly”, “stout”, “weather-beaten”, “easy” and a “drunk”. And that’s it. The life and times of Peggy Richards was summed-up in the public’s mind by five cruel words, which didn’t portray her a defenceless victim of murder... ...but as a criminal who deserved to die. Thursday 19th February 1942. With the Nazis advancing, most of Europe having fallen and the Allies in retreat, it was dark times, as German bombers rained down death from the skies. One week earlier, the Blackout Ripper had been arrested for slaughtering four woman, but it barely made the papers. Having fought with her lover on Valentine’s Day, for almost a week, Peggy had slept in a slew of flea-bitten hotels if her pissed-up punters could afford it. But when they couldn’t, she slept rough. Simply to exist, she sold her body for sex. Each day wearing the same tatty clothes; a red crepe dress, a black wool cardigan, a fake fur coat, black stockings and a red scarf wrapped around her head like a turban. In contrast, billeted at Witley Common Camp where every soldier was given good food, a clean bed and a solid wage – having sent a few dollars back to his wife and child in Canada - Joseph and his pals headed to Waterloo in search of drink and girls. As a Private, he wore blue Glengarry trousers, a tunic and a beret, with a bright red pompom on top and bearing the badge of the Ottawa Cameronians. And as if it wasn’t already obvious which of these two people our governments valued more; Joseph carried an Army issue gas-mask, and where-as all Peggy had to protect her was a half-empty handbag. That evening, Joseph disembarked his train at Waterloo Station, his pal said “what about drinks and some women?”, Joseph agreed, they bought a pack of prophylactics and sauntered to the closest pub. At 7pm, the barman of the Hero of Waterloo pub at 108 Waterloo Road saw ‘Peggy’ enter the saloon bar in the company of two Canadian soldiers (one of whom was later identified as Joseph McKinstry). At 8pm, the threesome headed to The Wellington Hotel, a pub directly opposite at 81 Waterloo Road, where they drank until closing time at 10.30pm, and purchased a few bottles of beer as off-sales. In his own words, Joseph said “I asked her to go out” – which was a common code for sex – and having stumbled into Alaska Street; a rotten unlit crevice of festering bins, scuttling rats and puddles of urine, under the roar as trains thundered overhead – “I had her in a doorway”. He paid her five quid without quibble and as his pal tottered back to the station, Joseph & Peggy headed towards Waterloo Bridge. That was the last time that Peggy Richards was seen alive. Three weeks from its opening to pedestrians, Waterloo Bridge was under construction. With no traffic, no lights and being in blackout, it was difficult to see a few feet ahead, let alone the black river below. Joseph would later admit to detectives: “we went for a walk, she was annoying me, I barked at her ‘oh shut up you goddam bitch’, and as we sat on parapet of the bridge... I had her again”. At 11:55pm, the storekeeper for Lind & Co and his colleagues – a lighterman, a night-watchman and a GPO engineer - heard the sound of arguing on the bridge. Exiting the storeroom by the south shore door, they clambered up the concrete stairwell and spotted a lone man looking over the parapet. The storeman’s torch illuminated the soldier’s face and the word Canada on his tunic. In his right hand was a beer bottle, the soldier (identified as Joseph) reassured them “I’m alright mate” stating his pals had crossed the bridge, as in his left hand he pushed an unseen object into his respirator case. Owing to obstructions, the night watchman guided him to safety and he staggered north to Covent Garden. Unsure what had occurred, the storekeeper and his co-workers searched the unlit bridge by torchlight, finding only a scarf wrapped like a turban by the parapet, two feet from where the soldier had stood. They shone their torches down into the black muddy river below... ...but they saw and heard nothing. At 1:30am, Joseph was seen at the YMCA canteen on Platform 15 of Waterloo Station, trying to get a ‘chit’ to stay at the Union Jack Club, a servicemen’s club at 91 Waterloo Road. Short of sixpence for a night’s bunk, a fellow Canadian spotted Joseph ferreting for silver in a handbag (matching Peggy’s), smoking a ‘Churchman’ cigarette (the type Peggy smoked) and the soldier reported him to the Police. When asked by a Constable “do you have anything in your possession which doesn’t belong to you”, Joseph (who had given a false name) replied “no”, but when pressed, he grew petulant and threw it onto the table, claiming he’d been with a woman drinking “she hit me with the bag and then ran off”. The handbag held ration books in the name of Peggy Richards, the bottom right lens of his spectacles was cracked, his dentures had broken in half and across his forehead was a small swelling bruise. Unable to find a witness, including Peggy, to either confirm or deny his story - being a Canadian soldier – Private Joseph McKinstry was dealt with by the Provost Marshall of the Ottawa Cameronians, but was released without charge. After a good night’s sleep, Joseph returned to his barracks in Surrey. Nobody was worried about Peggy’s safety... ...as no-one reported her missing. The next day, on Friday 20th February 1942, at a little after 6:30am, as a slim crack of dawn-light pierced the dull grey clouds - still unable to rationalise that he thought he had heard - the storekeeper returned to the bridge’s parapet where a woman’s head-scarf was found and the soldier was seen staring down. Alerting the Police, at 9.35am, a patrol boat approached the south-west foreshore, under the shadow of Waterloo Bridge. Being half way between high and low tide, face-down in the silty mud, a body lay motionless; its fake fur-coat was matted, its red crape dress was sodden and its pale legs were buckled. Hoisted-up in a wicker cradle, a Police surgeon gave this anonymous woman a cursory once-over and proclaimed “another suicide, I suppose?”, stating his belief she had been dead four to seven days. And that was the end of Peggy’s story... ...an unloved and unattractive prostitute who in a pique of alcoholic depression jumped to her death; she was mourned by no-one, buried in an unmarked grave and (like unwanted litter) easily forgotten... ...or she would have been, had her autopsy not landed in the hands of a highly skilled pathologist who was hailed as brilliant, inventive, fastidious and – more importantly – sympathetic. At 2:30pm, in Southwark Mortuary, the corpse of Peggy Richards was laid on a cold marble slab before Dr Keith Simpson. Untouched, her pale face was daubed with red lipstick, cheap rouge and river mud, as he had expected. And although some of her garments had been disturbed by the natural flow of the ebb-tide, one stocking had slipped off, but – stranger still - her underwear was completely missing. The Police surgeon’s time-of-death was wildly-out. Detecting a temperature of 47 degrees Fahrenheit in her internal organs, having compared this to 38 degrees in the mortuary and a river temperature of 31 degrees, Dr Simpson estimated she had died 14 hours earlier – “about midnight, give or take”. And as for this being a suicide? Within a few minutes of seeing the injuries to this unfortunate woman, he had notified Superintendent Reece of the CID - “this is not a suicide... this is a suspected murder”. Across the middle of her back were jagged scuff-marks, small uneven tears similar to the dotted holes in her red crape dress, and situated at a height of three feet and six inches from her feet, they exactly matched the hard surface of the parapet’s wall, suggesting she had been forced against it. Being a sex-worker, it was impossible to prove whether intercourse had taken place in the moments before her death, but a psychical assault was very evident. Wiping away the mud, five fingertip bruises had encircled her neck (like a ghostly red hand) and the hyoid bone of the voice-box was fractured. Whether she fell or was pushed, her death occurred just moments after she was strangled... ...and although her motionless body was found in the River Thames, she didn’t drown. Tumbling backwards over the parapet, as Peggy’s body plunged a minimum of 10.8 metres or 30 feet, the shallow muddy foreshore should have broken her fall, but it didn’t. Owing to its design, directly below her was one of five solid piles used to support the bridge’s span. Weighing roughly twelve stone, Peggy hit this 4.3-metre-wide re-enforced concrete wall at a speed of roughly 38 miles-per-hour. Both thighs snapped, both knees broke, most ribs split and her chest cavity was crushed, and although her head remained intact, there were extensive injuries to her internal organs, as she bounced off the rock-hard surface (built to survive impacts from steel ships) and tumbled into the muddy foreshore. Alone, broken and (hopefully) unconscious, Peggy died face down in the mud. Four days later, Dr Keith Simpson concluded – “it was murder”. With an investigation in full swing, Police swiftly questioned the stockman and his three colleagues of Lind & Co; the barmen at The Wellington and The Hero of Waterloo pubs, the Canadian soldier at the YMCA, the Police Constable at Waterloo Station, the Provost Marshall and Peggy’s boyfriend. Having compiled a description of this unknown assailant – stocky, mid-forties, thinning hair and cocky, with cracked silver glasses, a bruised forehead and a broken set of dentures, wearing a blue uniform with a red pompom beret and the badge of the Cameronian Highlanders – given a list of every soldier on leave in London that day, they tracked down Private Joseph McKinstry to his billet in Surrey. Significantly, when he was found, he joked to his pals “goodbye lads, I’ll see you again... if they don’t hang me”, only – at that point – he hadn’t been informed why the police wanted to speak to him. Held in a detention cell at Bow Street Police Station, having been cautioned, Joseph asked “is your chief going to charge me with murder?”, the officer said “I don’t know, you are merely detained whilst further enquiries are made”, at which Joseph coldly stated “I am not going to remember too much of what happened on that goddam bridge, until I hear what he knows and what the witnesses say”. He gave a brief statement: “I had been with a girl, drinking. She hit me with her handbag as we came out of the pub. I got hold of it, she ran off and I got left with it”, but he denied assault and murder. With Peggy attacked on the 19th, found on the 20th and her autopsy concluded by the 24th, Joseph was arrested and charged with her murder on Wednesday 25th February – in total, it took just six days. Given a wealth of evidence and witnesses, the trial should have been a mere formality... ...but with Joseph being a Canadian soldier and Peggy a British prostitute... ...handed a political hot-potato, only one life would be deemed worthy. On Wednesday 15th April 1942, husband, father and solider, Private Joseph McKinstry was tried at the Old Bailey for the murder of Margaret MacArthur, alias Peggy Richards, and he pleaded ‘not guilty’. The evidence was overwhelmingly weighed towards his guilt; the prosecution had her scarf, handbag, cigarettes and silver coins; several sightings of this very identifiable man wearing his military uniform, an admission in his own words that “we drank and had sex twice” the last time being on the parapet of Waterloo Bridge directly above where her body was found, a thorough autopsy which had proven she was strangled by a right-handed man (which Joseph was), and the Police report even concluded that “there is no doubt that Joseph McKinstry was responsible for Peggy Richard's death”. On paper, Joseph McKinstry was as good as dead, and the hangman’s noose would await his neck. But from the start, his defence made it clear who was worthy and who was not; that Peggy was nothing but a common prostitute and Joseph was a brave soldier defending our country in our time of need. Arguing that her death was either an accident or suicide, they did everything to discredit the autopsy; disputing how Dr Simpson could prove she died at midnight using the temperature of her organs (a method which is standard practice today), suggesting that the fingertip bruises around her neck were crush-injuries caused by logs or lumps of iron in the water, and that although the blood in her liver showed that she only survived for ten minutes after the fall - without a shred of evidence – the defence argued she could have lived for four more hours... which put a question-mark over her time of death. The defence concluded: “there is no evidence that Joseph McKinstry was with Peggy Richards after 10:30pm and his presence with her on the bridge at midnight can only be inferred by his statements” – (Joseph) “she hit me with the bag and then ran off”– and being a sex-worker, it was suggested that she could easily have picked up “someone else”, and it was this unseen stranger who murdered Peggy. The jury agreed, and on Wednesday 22nd April 1942, Joseph was acquitted of Peggy’s murder. (End) The murder of sex-workers – especially during war-time – was (and still is) seen as little more than the occupational hazard of faceless nobodies slaughtered on London streets at an often-unreported rate; including Agnes Stafford, Mary McLeod, Evelyn Hatton, Margaret Cook, Rita Green, Dora Freedman, Ginger Rae, Evelyn Oatley, Margaret Lowe and Doris Jouenette to name but a few, but no-one cared. War-time juries were reluctant to convict any serviceman of a capital offence, especially allied soldiers like Americans or Canadians, as this was likely to cause an unnecessary rift between our nations. We’ve seen it all before, foreign soldiers convicted of murder – including Richard Rhodes Henley, Thomas Edward Croft, James Forbes McCallum, Henry Smith and George Brimacombe – only to have their executions commuted, acquitted, pardoned, or given a woefully lenient sentence, and returned home. Upon his acquittal, when Police returned some of his personal property, with his trademark arrogance and self-entitlement, Joseph asked “the money found in the dead woman’s handbag, can I have it?” In April 1942, Joseph returned to Canada as a free man, to enjoy his life and his future. A few months later, he and his unnamed wife conceived a boy called Roland. But in January 1944, tragedy struck when a fire engulfed their home in Hull; his wife, their 8-year-old daughter and 10-month-old son all perished in the flames, and yet sustaining just a few burns, miraculously Joseph escaped death... again. And as with Peggy Richards - just like the law – fate would only deem his life worth saving. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. As always, if you enjoyed that episode, there’s some non-essential extra stuff after the break. But before that, here’s a very exclusive message from our good friends at Cult With No Name. (Play Promo) If you enjoy listening to the Murder Mile theme-tune – which is a track called Man In A Bag, track five from the album Heir of the Dog – also available as a ring-tone – and Winsome Lose Some (the end credits track you can hear right now), as well as many other tracks used across this podcast, their full back catalogue is available via the link in the show-notes. I own every album by Cult With No Name, I’ve been to most of their gigs, and they’re all great. Nights in North Sentinel is their 10th album launching on 30th July, and it’s an intoxicating audio tour-de-force of joy, love and loss. I loved it. As musicians, Erik & Jonny are not afraid to push the envelope, to roll out something original and different in each album, and best of all, they’re really lovely people. To support local musicians like Cult With No Name, click on the link and have a listen. A big thank you to my new Patreon supporters, who are Victoria Mcloughlin, Tim Newbound, Jennifer Trebon, Jessica Cheeseman and Rob Richardson, I thank you all, and – if like me you are dying in the heat – don’t forget that a Murder Mile mug also makes beer and wine cooler and taste great. Plus, a little reminder, that CrimeCon “the world’s number 1 true crime event” is coming to London on Saturday 25th and Sunday 26th September. It’s the “ultimate true crime weekend”, sponsored by the Crime & Investigation Channel; a two day event full of criminologists, profilers, authors, journalists, film makers and some of the real life survivors, with 5 stages, 50 hours of content, live discussion and presentation, you can meet loads of likeminded true crime enthusiasts and we also have Podcast Row which features oodles of your favourite podcasters including me. Phwoar To take part, click on the link in the show-notes and use the offer code MILE for 10% off, plus you’ll get a little gift from me. And – because this virus is still being a bit of a bellend – every ticket comes with a full refund guarantee. So, grab one of the last tickets, as I’d love to meet you there. Murder Mile was researched, written and performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of the fabulous Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER The Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast has been researched using the original declassified police investigation files, court records, press reports and as many authentic sources as possible, which are freely available in the public domain, including eye-witness testimony, confessions, autopsy reports, first-hand accounts and independent investigation, where possible. But these documents are only as accurate as those recounting them and recording them, and are always incomplete or full of opinion rather than fact, therefore mistakes and misrepresentations can be made. As stated at the beginning of each episode (and as is clear by the way it is presented) Murder Mile UK True Crime Podcast is a 'dramatisation' of the events and not a documentary, therefore a certain amount of dramatic licence, selective characterisation and story-telling (within logical reason and based on extensive research) has been taken to create a fuller picture. It is not a full and complete representation of the case, the people or the investigation, and therefore should not be taken as such. It is also often (for the sake of clarity, speed and the drama) presented from a single person's perspective, usually (but not exclusively) the victim's, and therefore it will contain a certain level of bias and opinion to get across this single perspective, which may not be the overall opinion of those involved or associated. Murder Mile is just one possible retelling of each case. Murder Mile does not set out to cause any harm or distress to those involved, and those who listen to the podcast or read the transcripts provided should be aware that by accessing anything created by Murder Mile (or any source related to any each) that they may discover some details about a person, an incident or the police investigation itself, that they were unaware of. *** LEGAL DISCLAIMER Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|