|

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

Welcome to the Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast and audio guided walk of London's most infamous and often forgotten murder cases, set within one square mile of the West End.

EPISODE SEVENTY-SEVEN:

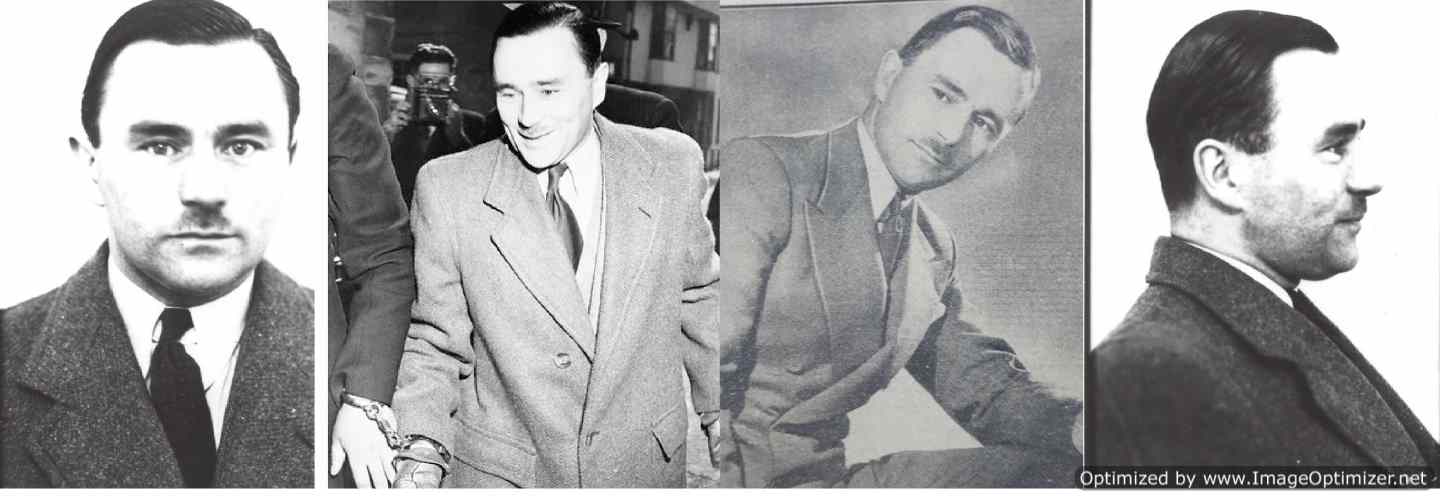

On Monday 28th February 1949, 39 year old John George Haigh; an amiable and smartly-dressed director of an engineering firm sat in interview room three of Chelsea Police Station, assisting the police with the disappearance of his friend Mrs Henrietta Durand-Deacon. And yet, in this interview, Johnny Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers would brazenly confess to six perfect murders, knowing that without a body, the Police could do nothing.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations (and I don't want to be billed £300 for copyright infringement again), to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

I've added the location of Chelsea Police Station on 2 Lucan Place marked with a red dot. To use the map, simply click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, Paddington or the Reg Christie locations, you access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable. Sadly, as photo of Emily & Patrick are copyrighted, I can't post them here.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: This series was researched using the original declassified police files held at the National Archives, the Metropolitan Archives, the Wellcome Collection, the Crime Museum, etc. MUSIC:

SOUNDS:

TRANSCRIPT: SULPHURIC:1 JOHN GEORGE HAIGH (Serial Killer)

For the best part of an hour and a half, the two men sat opposite each other in a small dimly-lit room; they smoked, made small-talk, did the crossword and occasionally (as bouts of boredom took him) Johnny had a little snooze, as Albert kept him fed and watered with a steady supply of tea and toast. Earlier in the afternoon of Monday 28th February 1949, 39 year old John Haigh; a respected director of an engineering firm (who was Johnny to his pals and Sonny to his beloved parents) had once again volunteered his time to assist the Police following the disappearance of his good friend, co-tenant and prospective business partner, Mrs Henrietta Durand-Deacon, who he had reported missing. Interview Room Three of Chelsea Police Station was barely big enough for two men, let alone four, so being just eight foot square with no windows, a small table, four wooden chairs and only one door, as Chief Superintendent Thomas Barratt and Divisional Detective Inspector Shelley Symes had stepped away, Detective Inspector Albert Webb and Johnny Haigh passed the time, awaiting their return. Johnny was an unassuming little fellow; five foot eight and ten stone at a push with a weedy little body that a stiff breeze could easily blow over. Raised well; he was polite, calm and respectful. As a dapper middle-class gent’, he was fastidiously neat with shiny black shoes, a starched shirt and a smart brown suit, topped off with a red tie and socks as a bold flourish of colour. And although Johnny was just a few weeks from his fortieth birthday, he looked almost boyish; being blessed with a little round face, dimples in his cheeks, a neat side parting and a feeble little moustache, who spoke well and never swore, but always at a slightly feminine pitch, as if his voice had never broken. Yes, it’s fair to say that Johnny Haigh was a pleasant sort of chap, who was unassuming, unthreatening, amiable and easily forgettable… and although they couldn’t prove it, the Police suspected otherwise. Being locked in an airless box, a ticking clock, a numb bum and Webb saying nothing as years in the force had taught him the unsettling power of silence; at 7:15pm, Johnny piped-up (Haigh) “What are they doing now? Symes and Barrett I mean”. Webb bluntly uttered (Webb) “Well John, I don’t really know, but I should imagine they are working hard in order to get you hanged”. Unperturbed, Johnny asked “Hanged, what on earth for?”, falling into the trap which Webb had set (Webb) “Oh, you know very well that they only hang people for one reason in this country, don’t you John?”. And he did. Over the last five years, unassuming little Johnny Haigh had befriended six wealthy persons; the Swan family, the Henderson’s and Mrs Durand-Deacon; he had assumed their identities, inherited their estates, drained their assets and all six had mysteriously vanished, and almost no-one had noticed. And as a cocky impish grin spread across his boyish face and his eyes (like cold dark marbles) twinkled, Johnny smirked (Haigh) “You can’t prove I murdered anybody. You can’t prove a murder without a body”. As with a callous coolness, the little killer quipped “…you know those people that disappeared. They no longer exist. No trace of them will ever be found. If I told you the truth, you would not believe it”. And yet, right there, in Interview Room Three at Chelsea Police Station, John George Haigh, one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers would brazenly confess to six perfect murders; the how, the where and the when, every single detail… but without a body, the Police could do nothing. (Whisper) Sulphuric. (Fizzes, tails off) John George Haigh was born on 27th April 1909, the only child of John & Emily Haigh, a mining engineer and a housewife; thirty seven years old, married for eleven and faithful right through their old age. Johnny’s entrance into the world was unremarkable. Born in the bedroom of a small terraced house at 22 King’s Road in Stamford (Lincolnshire), a respectable upper-working-class street for the skilled and educated in a prosperous mining community, although a little small, his birth was uneventful. As a baby, he was no bother at all; he slept well, ate well, played quietly, rarely cried and being blessed with no diseases, disabilities or deformities, his health was never an issue. In fact, as to be expected from a family with no history of drink or drugs, assaults or abuse, instability, insanity or incarceration, as a good boy who never had a tantrum, there were no significant events which troubled his early life. In 1910, the family moved to a larger home at 112 Ledger Lane in Outwood, north of Wakefield and for the rest of their lives, they suffered no period of unemployment, poverty, depression or separation. As a boy, John whole-heartedly adopted his parent’s beliefs by becoming a member of the protestant nonconformist sect, the Plymouth Brethren. A small puritanical group with a strict moral code, a dour formal dress and an unflinching politeness, who believed that The Bible was the word of God, so unless it is expressly stated, everything was forbidden; including Easter, Christmas and wearing crucifixes. So devout were the Plymouth Brethren, they shunned anything that distracts from the serving of God. Hence the Haigh household was always neat, clean but sparse, and with no radio, newspapers or books (except The Bible), they kept their minds pure, their hearts innocent and all sins at a distance. And to ensure this, hospitality was forbidden, friends were limited to those of their tiny congregation and John Snr built an eight foot wall around their back garden to shield them from any outside influences. It may seem severe, but Johnny embraced his faith which stayed with him for most of his life. To any outsiders, although the Haigh’s bristled with an unpleasant air of superiority – often being cold, aloof, distant and quite snooty - by living closer to The Bible, they never intended to offend anyone, all John & Emily ever wanted was to serve God and to do the best for their son. Aged seven, John went to Prep School. Being a little boy dressed in smart suits, shiny shoes and bow-ties, he was often bullied, but buoyed by his faith he brushed-off these insults without any emotion. Aged eleven, John won a prestigious scholarship to Wakefield Grammar; a Church of England school attached the Wakefield Cathedral, and although its teachings conflicted with their strict beliefs (having become an altar-boy, a chorister and an organist having learned the piano), his loving parents were so proud that they fully supported him throughout his education. And it served him well. During those awkward teenage years, Johnny remained an even-tempered boy, who didn’t shout, swear, smoke or drink, but had no issues with those who did. He didn’t fight, start fires, steal and had no sexual issues; in fact, although a late-bloomer, he later became celibate, fearing the rampant rise of sexual diseases and seeing women as more companions than conquests. He disliked loud noises, dark places and germs, and being an only child with very few friends, he had a puppy, who he adored. These principles laid down by his parents put him in good stead for the rest of his life. Although lonely, Johnny was a good talker and a keen listener. Although isolated, Johnny was a regular church-goer and an enthusiastic student at the school science club (who was fascinated by machinery and chemistry). But as a bright but easily bored boy, although he won prizes in Geography and Divinity, his grades were not great. So, for fear of upsetting his proud parents, and eager to please them, he forged his school master’s handwriting, creating glowing reports which fooled everyone. Upon graduation, Johnny failed to pass his school certificate. But John & Emily Haigh weren’t upset or disappointed; yes he had lied, but they had raised a good, decent and moral boy, of above average intelligence, who dressed well, spoke politely and dreamed of a career in engineering, and (no matter what path he chose in life) they knew that their little boy would always excel at his chosen profession. And yet, for the first twenty-seven years of his life, as decent human being, he had achieved a lot, but as one of Britain’s most infamous serial-killers, John George Haigh had done nothing. (Interstitial *) * For interstitials, whisper “Sulphuric”, followed by fizzing. Twelve years and six deaths later, Johnny Haigh – the entrepreneur; who lived in a Kensington hotel, drove a red sports car, wore silk shorts under his sharp suits, and was a tad miffed at missing not only luncheon, but also tiffin, tea and now din-dins - sat in Interview Room Three of Chelsea Police Station; flanked by Barrett, Symes and Webb, three shabbily-dressed coppers whose hand-rolled tobacco, stale sweaty suits and cheap shop-bought aftershave was an insult to his more-refined sense of smell. And as Johnny candidly talked, the Police listened. (Haigh) “I have made some statements to you about the disappearance of Mrs Durand-Deacon. The truth is, we left the hotel together and she was inveigled by me into going to Crawley. Having taken her into the store-room at Leopold Road, whilst she was examining some paper for use as fingernails, I shot her in the back of the head. Following that, I removed her coat, jewellery and disposed of her. Oh, I should have said that in-between, I went round to a cafe for a cup of tea and scrambled egg”. Throughout, although he was polite, calm and controlled, his boyish face beamed with a cockiness, as being pleased-as-punch at his own superiority over the Police, he knew he could tell them everything, but - without a body - they could prove nothing. (Haigh) “Any more toast?” (Interstitial*). From his teens to his twenties, Johnny worked as a salesman at Shell Max, a sign company rep’ and as an insurance clerk where he learned the finer legal points of Hire Purchase agreements, but finding the long hours, hard graft and tiny wage unrewarding, his work record was described as “satisfactory”. And why wouldn’t it? As an easily-distracted dreamer with wide eyes and high hopes, his commute from his sparse, starchy and silent home to the bustling city of Leeds in the grip of the Roaring Twenties must have felt like the boy had entered a brave new world; a sensual orgy of dizzying delights, fizzing with fast cars, fine foods, gangster films, flapper girls and filthy Luca… everything he had been denied. But as a teetotal celibate, Johnny didn’t descend into debauchery, as his only vice was pride. Fuelled by middle-class aspirations; he dressed in smart suits (neat like his mother made but topped-off with a flash of red as a tiny act of rebellion), he bought a wireless radio (shocking, I know, but he didn’t besmirch his ears by listening to anything vulgar like jazz, only classical, which his father approved of), yes he secretly owned three cars - Ford 8, a Talbot Daracq and an Alpha Romeo – which he and his pals raced from Leeds to Scarborough; okay he dabbled a tad at the horse-track but only because he loved the thought of making oodles of cash without the hard graft; and yes, okay, although never charged, his dismissal from the sign company did coincide with the theft of a petty cash-box, which he apologised for and his father paid back all of the missing monies, so considering how his life had begun, surely these were nothing but little acts of indiscretion which were forgiven and forgotten? On 6th July 1934, a little later than most men, 27 year old Johnny Haigh married 23 year old Beatrice Hamer, a pretty blonde waitress he had met just a few months prior, who was smitten for his sweet-face and dazzled by his cheeky charm, but this wasn’t love… at least not for him. Johnny did feel love. After a quickie service at Bridlington Registry office; with no wedding bells, no bridesmaids, no cards, no confetti, no readings, no religion, one witness and no parents, Johnny & Beatrice Haigh moved into their own home in Leeds, but this wasn’t a marriage… at least not for him. Johnny didn’t do marriage. Although a pleasant companion, Beatrice was more of a convenience to free the boy from the austere shackles of his stifling parents, and although (as they always did) they forgave him, being burdened by responsibilities, his wife was now little more than an impediment to his dreams of prosperity. Scraping-by on a paltry £3 per week was no way for a budding entrepreneur to live. How on earth could Johnny be seen as a real go-getter when he never stayed in swanky hotels, rarely ate prime-rib steak, his suits were so last season, his blasted bank balance always bled-dry and he only owned three sports cars? No, this would not do, not by a long shot. On 28th June 1934, just one week before his wedding, having perfected the skill of forging a stranger’s handwriting and mastering the finer legal points of Hire Purchase agreements, in a simple scam where they resold rented cars on forged papers, Johnny and two cohorts defrauded the three insurance firms - Mercantile Union, Bowmaker Ltd and United Finance Company – out of £960, almost £60,000 today. In his eyes, it was a victimless crime. I mean, he wasn’t snatching old lady’s handbags, breaking into young mum’s homes or scaring the bejesus out of bank-tellers with dicky hearts. He didn’t use a gun, he used a pen, and let’s not forget, no-one was hurt and nobody died. So really? What harm was done? On 22nd November 1934 at Leeds Assizes, John George Haigh was found guilty of three counts of fraud with six similar counts taken into consideration and he was sentenced to fifteen months in prison. After six months, Beatrice gave birth to a baby girl who she named Pauline. But as a penniless single mother with a convict spouse who made no provisions for a wife and alleged child, so unable to cope, Pauline was put up for adoption. This wasn’t a family… at least not for him. Johnny didn’t do family. Life in prison was fine; the bedding was sub-par, the uniform was baggy and the food was far from filemignon, but Johnny made-do; by keeping his cell neat, his mind busy, his nose clean and devoting his time to prayer, education and silent reflection. And although an amiable little fellow whose charm made him an easily likable sort, Johnny wasn’t a low-life like the common criminals he had been banged-up with. No, his crimes had style, finesse and - just like him – they were superior in every way. His only remorse was for everything he had lost; his money, his suits, his cars and his reputation. On 8th December 1935, Johnny was released from prison. Having unburdened himself of a wife and child, he returned home to his loving parents; who would always support him through each test and trial, always forgave him for every sin and sentence, and always stood by him, even as – shamefully –their convict son was excommunicated from the Plymouth Brethren, and with his faith shattered, his heart stabbed and his pockets empty, John George Haigh had reached rock bottom. (Interstitial*) Throughout his full and rather frank confession in the stale smoky confines of Interview Room Three, as the self-confessed serial-killer spoke, Barrett, Symes & Webb listened intently. But never once did little Johnny Haigh stutter, flush or tremble, his voice never raised and his sweat never broke, as the only emotion he showed was a cocky little grin as he corrected the copper’s mistakes. Still it seemed odd, didn’t it? That a former member of the Plymouth Brethren would smoke Gauloises from something as ostentatious as an 18 carat gold cigarette box, that a fastidiously neat man would allow odd singe marks to sully the underside wrists of his tailored overcoat, and that such a slight and unassuming man could physically kill six people and leave no evidence with which to convict him. And yet, Haigh ploughed on: “Mrs Durand-Deacon no longer exists. She has disappeared completely and no trace of her can ever be found”, deliberately leaving a prolonged pause so Detective Inspector Webb could ask the obvious, (Webb) “Well, what has happened to her?”, his snort causing his little moustache to bristle, Haigh grinned (Haigh) “I destroyed her with acid. You will find the sludge, all that remains of her, at my storeroom in Leopold Road. Every trace has gone. And I did the same with the Henderson’s and the McSwan’s”. Which posed the Police with a real conundrum, if a body no longer exists, how can you prove a murder if the murdered are only missing? (Interstitial*). Post-prison, Johnny felt like a lost cause; he was too old to be living at home, to sinful to be welcomed back to the church, too solitary to be part of a criminal gang, and as a late-twenties unemployed ex-con dossing his elderly parent’s home in a small mining town in the North of England, now more than ever, he was further away from his dream. I mean, they didn’t even own a motorcar. In 1936, eager for a fresh start, Johnny moved to London. Dabbling in a few honest but ultimately unrewarding jobs including as clerk and chauffeur for a good-egg called William Donald McSwan Jnr, but hating the long hours, hard graft and tiny wage, once again, Johnny felt the lure of easy-money. On 24th November 1937, at Surrey Assizes, Haigh was convicted of seven counts of fraud having forged legal papers and falsely represented himself as a solicitor and stole £3200, almost £210,000 today, with a further twenty-two cases taken into consideration. His confidence was high, his scheme was clever and his crime was brazen, but his mistake wasn’t greed but speed, as on the letterhead he had misspelled the town of Guildford. Johnny was sentenced to four years in Wandsworth Prison Wealth was within a finger-tip’s touch, yes being banged-up was a minor set-back but, once again, his near perfect plan was scuppered by those unpredictable irritants - people – as whatever he stole, they would always want it back. But how could he make sure they would never notice the missing monies? Released on licence on the 13th August 1940, the 31 year old repeat-offender returned to London only to see a ravaged smoking city; its blackened crumbling buildings silhouetted by a red fiery sea as if he had entered the bowels of hell, as night-after-night his whole world was bombed by the Luftwaffe. Businesses were destroyed, homes were smashed, lives were decimated, and as a ragged and hungry Haigh slept in flea-infested doss-house, the strict conditions of his early release was like walking a legal tight-rope. Ex-con Johnny had to go straight, as one little slip and he was back in the slammer. Only, like Leeds as a boy, although London was truly a den of debauchery, still being a teetotal celibate with dreams of becoming an entrepreneur, even at wartime, it was a city of extremes; with blackouts, bomb-craters and Bentleys; furs, famine and finger-food, destitution, decadence and death. And with his half-way house at the back of The Ritz, that was like waving cheese under a snoozing mouse’s nose. As part of his parole, Johnny did his bit for the war-effort being conscripted as a fire-watcher, alerting the fire-brigade to any art-treasures at risk of destruction by The Blitz. Again, the hours were long, the work - as he protected masterpieces worth a mint - and all for a paltry wage, And like most citizens, his war-time experience was not without its horrors. In a regular letter to his parents, Johnny wrote: “On one occasion, while on fire-watching duty, I was talking to a Red Cross nurse at a warden’s post. The sirens shrieked, bombs dropped and the nurse and I moved off to our places of duty. Suddenly, in a moment of premonition, I knew that a bomb would fall close by, so I dodged into a doorway and awaited the inevitable crash. It came with a horrifying shriek, and as I staggered up, bruised and bewildered, a head rolled against my foot. The nurse who but a few moment before had been gay and full of life, high ideals and a sense of duty, had in one instant been swept into eternity”. But as shocking as it was, the reality was this… in war-time sometimes people just disappeared. Johnny did his damnedest to go straight and to make his parents proud-as-punch. On and off for four years, he worked as a clerk for his old pal William McSwan (whose kindness always saw him through) and did odd-jobs for a solid chap called Allan Stephens, a mechanical engineer and owner of the Union Road Tool and Garage Company in Crawley; working at his workshop, clearing out his store-room and living in his family home with his wife Evelyn and his daughter Barbara. Johnny had landed on his feet. Except putting-up, getting-by and making-do was never Johnny’s style… …so on 11th June 1941, he was sentenced to twenty-one months hard labour. But not for a cunningly superior scam having embezzled an impossible fortune, ripped from the mega-rich, having faultlessly defrauded the insured using a litany of faultless forgeries. No. Strapped for cash, Johnny had illegally flogged-off an old fridge, five bunk-beds and sixty yards of cloth. And in prison once again, most galling of all - because of these crimes - he had been branded… a “petty” criminal. On 17th September 1943, he was released on licence and went back to square one. Or so it seemed. (Haigh) “When I first discovered there were easier ways to make a living, I did not ask myself whether I was doing right or wrong. That seemed to be irrelevant. I merely said ‘this is what I wish to do’. And as a means lay within my power, that was what I decided… if you’re going to go wrong, go wrong in a big way. Go after women – rich old women who like a bit of flattery. That’s your market”. By his release, Haigh had spent six of his thirty-four years in several prisons, including Wandsworth, Dartmoor, Chelmsford and Lincoln. (Haigh): “Lincoln. The worst prison I have ever known is Lincoln. I resented it most bitterly and made up my mind that after this there would be no more inside for me”. But unlike the petty pilferers and common-criminals who frittered the endless hours, days and weeks by pinching snout, blagging sweets and smuggling smokes in a stash of old socks, Johnny dreamed big. As his cell-mate in Chelmsford later stated “he said he’d aim at half a million quid before he’d quit, but everyone just took it as a joke”. Another bunk-buddy stated “he kept gabbing on about this ‘corpus delicti', so that’s what we nicknamed him”. ‘Corpus delicti’, an 18th century English law, also known as the ‘bloodless murder law’ states that “without a body, there can be no crime”. Oddly Johnny had stumbled across it in the prison library, but around these two little words, his masterplan was born. The problem was it’s almost impossible to make a body completely disappear. (Interstitial* - End) Prisoner Haigh was an unassuming little fellow; petite, polite and polished who devoted his time inside to being an altar-boy and organist in the chapel, he starched his shirts, he made his bed and – always with a please and a thank you - Johnny was charm personified. So being a bright but easily bored boy, who once excelled in the school science club, he was given a much-lauded job in the prison workshop. When he wasn’t spending long hours cutting fresh tin into prison cutlery, zinc-plating the handles onto kitchen pans and cleaning rusted iron with sulphuric acid, which stripped his soft skin to a red raw mess and stung his nose with noxious choking odours – that aside – the workshop was the perfect place to fill his endless hours as his restless hands and curious mind fixed, fiddled and tinkered. Here his entrepreneurial spirit truly flourished, and yet, never once did he make, mould or even invent a single thing to make his fortune. No, but it was here that he devised the final piece of his grand plan. By 1944, John George Haigh was back on the streets; a small thin ex-con with a weedy frame, a boyish face, a feminine voice, a charming smile and a truly ludicrous dream to become rich without actually working; only he had no money, no home, no skills and he knew almost no-one. For the first twenty-seven years of his life, unassuming little Johnny Haigh was little more than a lost boy eager to please his parents. Over the next eight years, he was nothing but a failed petty fraudster who (at every turn) had lost everything. He didn’t drink, smoke or swear, he wasn’t violent or sadistic. But between 1944 and 1949, he would befriend six wealthy persons; the Swan family, the Henderson’s and Mrs Durand-Deacon; and – with near perfect precision - he would assume their identities, inherit their estates, drain their assets and all six victims would mysteriously vanish, leaving no trace with which to convict him. John George Haigh would become one of Britain’s most infamous serial killers… …and it all began with a dead mouse. (Interstitial* fizzing to fade out) OUTRO: Friends. Thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile, that was part one of Sulphuric; the true story of John George Haigh, with the second part of six continuing next week. A big thank you to my new Patreon supporters who are - Jayne Heath and Miss Marston (aka Sandra) – with (as always) a big thank you to everyone who has taken the time to like, share, comment and review this small independent podcast. It’s very much appreciated. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well.

The Murder Mile Threadless Store

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards 2018", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|