|

Nominated BEST TRUE-CRIME PODCAST at British Podcast Awards 2018, The Telegraph's Top Five True-Crime Podcasts, The Guardian's Podcast of the Week, Podcast Magazine's Hot 50 and iTunes Top 25. Subscribe via iTunes, Spotify, Acast, Stitcher and all podcast platforms.

EPISODE EIGHTY-SIX:

Today’s episode is a romantic wartime tale about Barbara Shuttleworth and Felic Sterbe, who amidst the ruins of a bombed-out London found comfort in each other’s arms, and yet, something lead these two “lovers” to end their lives in a truly bizarre death pact… well, sort of.

THE LOCATION

As many photos of the case are copyright protected by greedy news organisations, to view them, take a peek at my entirely legal social media accounts - Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

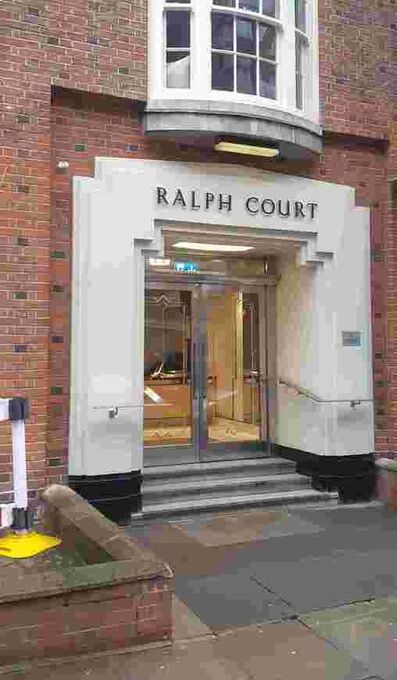

The location of Ralph Court at 210A Queensway is marked with a green triangle. To use the map, click it. If you want to see the other murder maps, such as Soho, King's Cross, Paddington or the John George Haigh or Reg Christie locations, you access them by clicking here.

I've also posted some photos to aid your "enjoyment" of the episode. These photos were taken by myself (copyright Murder Mile) or granted under Government License 3.0, where applicable.

Credits: The Murder Mile UK True-Crime Podcast was researched, written and recorded by Michael J Buchanan-Dunne, with the sounds recorded on location (where possible), and the music written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Additional music was written and performed as used under the Creative Common Agreement 4.0.

SOURCES: The original police file from the National Archives marked as Murder of Barbara Shuttleworth by Lt Colonel Felic Jan Sterba, who committed suicide, at Queensway, W2 on 30 July 1948 – http://discovery. nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C1258468 MUSIC:

TRANSCRIPT OF THE EPISODE: THE "LOVER'S" DEATH PACT.

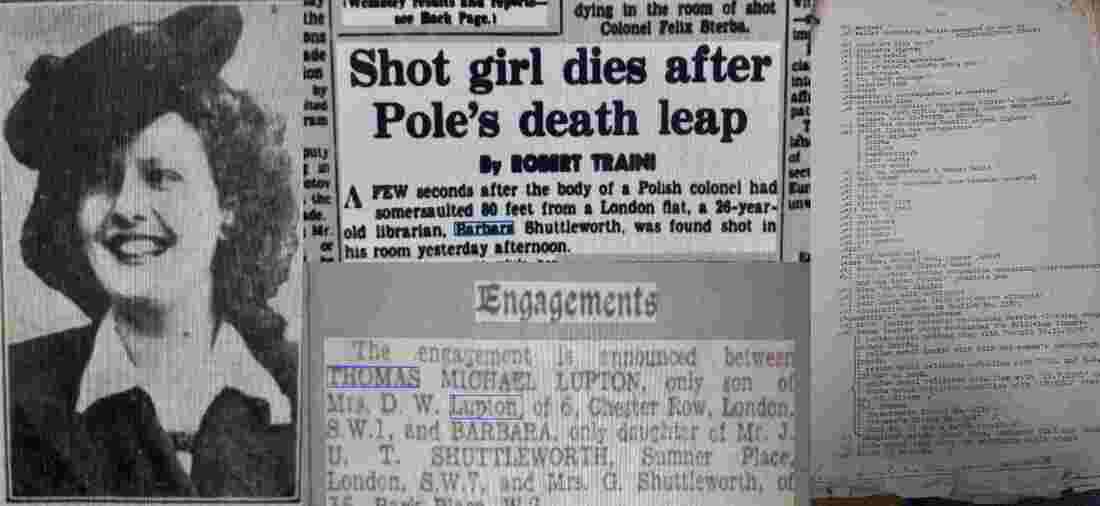

SCRIPT: Welcome to Murder Mile; a true-crime podcast and audio guided walk featuring many of London’s untold, unsolved and long-forgotten murders, all set within and beyond the West End. Today’s episode is a romantic wartime tale about Barbara Shuttleworth and Felic Sterbe, who amidst the ruins of a bombed-out London found comfort in each other’s arms, and yet, something lead these two “lovers” to end their lives in a truly bizarre death pact… well, sort of. Murder Mile is researched using the original police files. It contains moments of satire, shock and grisly details, and as a dramatization of the real events, it may also feature loud and realistic sounds, so that no matter where you listen to this podcast, you’ll feel like you’re actually there. My name is Michael, I am your tour-guide and this is Murder Mile. Episode 86: The “Lover’s” Death Pact. Today I’m standing on Queensway in Bayswater, W2; one street south of the dry-run jewellery heist for the Charlotte Street Robbery, three streets north-west of The Blackout Ripper’s final victim Doris Jouanette, a short walk north of the site of the Hyde Park bombing, and a little dawdle from the untold truth behind the memorial to murdered Policeman Jack Avery – coming soon to Murder Mile. Queensway is a bit of a dog’s dinner; being uncomfortably wedged between the piss-poor gloom of Paddington and the pretentious arseholery of Notting Hill, like a fibrous poo stuck up a pensioner’s backside, this side of Bayswater is a mess; it has no idea what it is, what it was, or what it wants to be. It’s a chaotic mass of Georgian townhouses, yucky new-builds, nasty 1960’s shops and crumbling high-rise flats, as if the council gave the architect’s job to a sugared-up toddler throwing a tantrum with his Lego. But as a mix of wealth and culture, what you can buy for 99p at Akmal’s discount cash & carry is also flogged-off for five times the price next door at Susie’s Splendiferous Yummy Mummy Parlour, where the thick-as-shit wives of wealthy stockbrokers are duped into buying utter crap by adding an adjective to everyday items; like vegan bikes, veggie wigs, fair-trade farts, meat-free meat, leopard-print pants for the lactose intolerant, ethnically-sourced air for the gluten-free and – everyone’s favourite con – beaded prayer mats rebranded as “authentic ethnic yoga mats” as used by Madonna, once, when she made some mumbo-jumbo religious twaddle fashionable for six whole seconds. On the corner of Porchester Road, at 210A Queensway is Ralph Court; an impressive eight-storey red-and-brown bricked mansion covering half a square block, but with no access except by locked doors and a glaring concierge, through the huge black gates (there to keep the riff-raff out) it looks a nice place to live. And although, in its central courtyard, some residents sit and lose themselves in a tawdry tale, they are unaware that just yards away was spun a truly strange tale of love, death and suicide. As it was here, on Friday 30th July 1948, on the seventh floor of Ralph Court, that two “lovers” entered a strange suicide pact, where both of them would die, but only one of them knew why. (Interstitial) But Barbara wasn’t just looking for love, she was looking for “the one”. In Autumn 1922, Barbara Sylvia Shuttleworth was born in the quaint market town of Knaresborough, four miles east of Harrogate and nestled amidst the breath-taking scenery of the Yorkshire Dales. Her upbringing was idyllic, as happily playing with her pals among the vivid hues of the moorland moss, the lush green valleys and the crystal-clear lakes – which had inspired great writers like J B Priestly, W H Auden and The Bronte Sisters – far from the choking smog of the city, her childhood was untroubled. As the only child of John; a retired Captain and affluent stockbroker, and Gwendoline; the grand-daughter of Sir Roland Barran, a pioneer in the manufacture of ready-to-wear clothing, although the Shuttleworth’s were well-off, they weren’t the idle rich, but came from a heritage of the industrious working-classes who prospered, not by inheritance, but by hard-work and struggle. And whilst many good persons struggled to survive in the austere shadow of the First World War, John & Gwendoline Shuttleworth ensured their daughter had it all – she had health, wealth and happiness. Privately educated at the same finishing school as her mother - tutored in etiquette, deportment and social grace - Barbara was raised to be a lady who was polite, moral and charming. An immaculately dressed woman with brown permed hair, an illuminating smile and a towering elegant stance. But a finishing school is not a university, and although she was also taught history and English, living in an era where a woman’s role was to look pretty and stay quiet, their misguided belief was that if a lady spoke proper, stood upright and had a smattering of brains to make small-talk with a potential suitor, she would find herself a good man, marry well and would live a full and good life, as his wife. It was an old-fashioned notion that had led Barbara’s parents to wed… and subsequently divorce. By the outbreak of World War Two, as an avid-reader of history and poetry, 17-year-old Barbara had found her true passion in the London libraries. By the middle of the war, like most people, the barrage of bombs had become just an annoyance to this independent woman who sought a career and maybe (if she had time) a man. And by 1946, aged 24-years-old, still single but sifting a slew of suitable suitors who - regardless of their age, title or wealth, above all - had to be someone she actually loved, when the bombed bits of the House of Commons were rebuilt, the British Government established a very modern Research Department in the Palace of Westminster and hired Barbara as its assistant librarian. Barbara Shuttleworth was a well-balanced woman with a good career, a busy social life, a happy home life and – raised to be polite, moral and decent – she had her pick of the men who fell at her feet. One possible suitor was Lieutenant Colonel Felic Sterba… and he would love Barbara to death. (Interstitial) Although a military man, Felic was a man of his emotions… Felic Jan Sterba was born in 1897. His early life – just like Barbara’s - was idyllic. Home was a beautiful little farm at the foothills of the Tatra Mountains in the far south of Poland. So peaceful and tranquil was this tiny village, that even before a rickety funicular railway turned Zakopane into a popular ski resort – with its crisp fresh air, ice cold lakes and snow-capped peaks - it was famed as a health spa. As the youngest boy to three older sisters and the only son of a doting housewife mother who spoiled him rotten and a stern over-bearing father who scared him, like most children, Felic was the product of both parents – he was sensitive and thoughtful like his moma but intense and precise like his papa. So, as a physically tough but emotionally fragile little boy, whose sturdy body was hidden by a crisp starched shirt and whose penetrating gaze was magnified by thick-lenses glasses - burdened by a big heart and an overactive brain - he had a desire to be loved, but a need to be in control. On 30th November 1929, as a late bloomer, 31-year-old Felic married a pretty local girl called Maria, who he absolutely adored. Believing she was better than he actually deserved; to keep his wife happy, he built her a stunning timber cabin called Willa Sielanka in the Tatra mountains; as a meticulous man he crafted a solid career as a pilot in the Polish Air Force, ensuring she was never without; desperate to be a dad, on 19th July 1931, they gave birth to Andriej, a date he immortalised on a gold medallion worn around his neck, and - although cursed by a jealous streak and paranoid that this modest and faithful woman would leave him - he signified his undying love for his beloved Maria by inscribing her name and wedding date inside his gold ring and secreting a photo and lock of her hair in a gold locket. They had a lovely home, a good life and a happy family. He loved them both without question and the medallion, the locket and the gold ring, he would wear next to his body… until the day he died. (“Peace in our time”) On 30th September 1938, British Prime Minster Neville Chamberlain held aloft a sworn statement from German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, in which he assured the people of Europe that there would be peace in our time, but it was all a lie. On 1st Sept 1939 Germany invaded West Poland. By week two, war was declared. By week three, the Soviets had invaded East Poland. And by week four, with 70% of all Polish aircraft and armaments destroyed or confiscated, and with the country left defenceless, Poland had fallen and its people were now under both Nazi and Soviet rule. With the Polish Air Force obliterated, 43 year old Lieutenant Colonel Felic Sterba and the remaining pilots were forced to flee; by October 1939 he was in Romania, by December he was in France, and knowing that his wife and child would be safe in their remote mountain retreat - like most people – believing this whole hullabaloo would all blow over by the end of the year, he wasn’t unduly worried. But as the Germans drove West, the Allies were evacuated from Dunkirk and the Nazis paraded though Paris, with the enemy perched just 100 miles from the coast, on 30th June 1940 Felic fled to England He hadn’t seen his family in a year; every day away was torture, every mile apart was a stab in the heart, and although, as a prolific letter writer, the few letters which got through from his loving wife reassured her paranoid husband that they were alive, well and that she would remain forever faithful, as a tough military man who struggled to rein in his emotions, the only time he could be near his family was when he held his golden locket, medallion and wedding band. He was alone, lonely and broken. Two years later, as the war raged on, Felic was still stuck in England… …and then he met Barbara. As an Air Force veteran, Lieutenant Colonel Sterba was snapped up to train a new fleet of fighter pilots based out of Regent’s Park. With only wooden mock-ups for dry-runs, the training was mostly theory, but with the average rookie pilot’s lifespan being just sixteen minutes, time was short, turnover was high and - as a gruff no-nonsense officer - Felic demanded perfection. But the war-effort (for him) was just a distraction from the pain of missing his family and - when he was alone - he became depressed. For Felic, as he shuffled through London’s West End, all he saw was dirt, dust and death. After four years without his family, food tasted bland, time had no meaning and he drank to forget. Every day it rained… and then, the clouds parted, the sky turned blue and the sunlight shone. On 14th June 1943, whilst supping tea at the Lyon’s Corner House tearoom in Marble Arch, Felic met twenty-one-year-old Barbara Shuttleworth; she was bright, charming and beautiful, a breath of fresh air with a beaming smile who effortlessly breezed through the drab grey ruins of this bombed-out city; and as he became dizzy from the joyous sound of her songs and the sweet scent of her perfume - in a world so full of pain, chaos and horror - suddenly, the dead weight in his heart melted away. That night, in his diary, Felic wrote “met Basia”, the Polish word for Barbara. For Felic, she was a lovely girl who eased his pain, made him smile and shared his love of poetry. For Barbara, although she was a singleton with many suitors, as he was a decorated war-hero, a sensitive gentleman and a generous friend, he was a real catch for some lucky lady, and she was interested. Briefly, as often happens during war-time when love-sick soldiers are away from their spouses, a little bit of innocent flirtation blossomed into a romantic dalliance, but as she was half his age and he was a happily married man, it was never meant to be, so knowing that once these hostilities were over that he would return home to his wife and child, they would simply remain as just good friends. (Churchill) On 2nd September 1945 - with Hitler dead and the Nazis defeated – as a hundred thousand strong crowd of excited people erupted in jubilant celebration across Trafalgar Square, Barbara and Felic kissed and cheered, as after six long years of fear, the war was finally over… …but as the street party died down, for many allies, a new war had only just begun. With Germany split and a supposedly-peaceful Europe being sliced-up between the democratic West and the Communist East, Poland was placed under Soviet control. Having fought against a Nazi dictatorship and died to defend this country, the Polish forces rightfully felt cheated, as they were forced to exchange one brutal regime for another. So, as millions of soldiers kissed their loved ones and returned to their everyday lives, like many Polish troops, for now, Felic was stuck. On 9th September 1946, having been separated from his wife and child for seven years, Felic enlisted in the 50th Officer’s Holding Unit of the Polish Resettlement Corp - a detachment designed to ease his transition from military into civilian life - until it was safe to return to his country… but he never would. Over the next two years, Felic became lost; he was a soldier with no war to fight, a pilot with no plane to fly, a father with no child to raise and a husband with no wife to love. He has nothing. So as the hours, days and weeks passed-by, with nothing to do and nowhere to go, he would sit in his bedsit, alone with nothing but his thoughts. All he knew was the military life… and all he had left was Barbara. For Barbara, the end of the war meant business as usual. Her homelife was good; with her lovely floral townhouse untouched by the blitz, she still lived with her mother at 35 Bark Place in Bayswater and often saw her father in Knightsbridge. Her work life was solid; with the government busy, she had been promoted to senior assistant librarian in the Palace of Westminster. And having waded through a slew of potential suitors, her love life had blossomed, having got herself a boyfriend. He was charming, he was kind and he was sweet… but he wasn’t Felic. In his eyes, Barbara was his lover. In her eyes, Felic was her friend. Their relationship which was never meant to be and with their brief flirtation having come to an end five years ago, as much as Barbara had tried to distance herself from Felic – as a lady who was raised to be moral, charming and polite - it was hard for her to sever all ties with a sweet man who so broken. She had to end it… but how? At home, she’d be sent his letters. At work, she’d get his gifts. Outside her window, she’d see his face. And every night, sometimes twice, she’d hear his phone calls. He was a married man who was double her age and she didn’t love him… but he couldn’t see that. So, as much as it hurt her, Barbara broke off contact with Felic, hoping that silence would cause him to forget all about her … only it didn’t. Her silence only made him more obsessed. With no life, he had nothing else to focus on… but Barbara. In late 1947, paranoid that his wife had been unfaithful, and (ironically) seeing her as his only obstacle to being with his one true love, Felic applied for a divorce, informed Barbara by letter, but got no reply. In Christmas 1947, he made two gold medallions, inscribed with ‘FS’ for Felic Sterba, ‘BS’ for Barbara Shuttleworth and on the back wrote ‘London’. His he hung around his neck, but hers was never found, And as eight months passed in silence, being sat in his lonely little bedsit on the seventh floor of Ralph Court, he filled his diary with nothing about his life, just his many failed attempts to contact Barbara. Sunday 18th July, the entry read “phoned Basia”. Monday 19th: “was in Basia’s home, was wonderful”. Tuesday 20th: “phoned Basia”. And yes, she had made contact and let him in, as she had something important she needed to say, she just didn’t know how to say it without breaking his heart. Wednesday 21st: “phoned Basia”. Thursday 22nd: “Basia didn’t turn up, Mother ill”. Friday 23rd: “Basia didn’t phone”. Saturday 24th: “Basia didn’t phone”. Sunday 25th: “Basia didn’t phone”. Monday 26th: “Basia didn’t phone at 10pm, I was under her window”. And Tuesday 27th: “no news from Basia, I am afraid she is ill or doesn’t live any more. I am long time without news. Is it the end with us? I phoned and asked her if she is alive. I have to speak with her. In the evening, I was under her window”. That day, she had to speak to him to before he saw what her mother had prematurely placed in The Guardian, The Times and the Yorkshire Post newspapers, it read; ‘the engagement is announced between Michael Thomas Lupton, the only son of Mrs D W Lupton of Chester Row, Belgravia, and Barbara, the only daughter of John and Gwendoline Shuttleworth’. Felic didn’t see it, but she still needed to tell him this to his face, as - being raised proper – she knew it was the decent thing to do. Wednesday 28th: “phoned Basia, I think we will meet”; it was a small sliver of hope, and although the call was only brief, it buoyed his spirits as on Thursday 29th: he wrote “Basia promises, said she would come tomorrow at 1pm”, but Barbara had things on her mind. That evening, over a romantic candle-lit dinner in a lovely little bistro in Bayswater, a besotted Barbara clinked champagne flutes with her fiancé Thomas - it was a glimpse at their happy life ahead. Together, the smitten couple held hands, kissed and – to everyone who saw them – they were very much in love. After a two-year courtship, with the time being right, they were engaged, soon-to-be married, and – with the purchase of a little flat in Highgate almost complete – Thomas slid his lover the key to their first home together, and as she left, in Thomas’s own words he said “she was absolutely ecstatic”. …but Felic had made his decision. His last diary entry on Friday 30th July 1948 simply read: “Basia will come at 1pm. God knows how it will be. Perhaps we will perish? The end of the last chapter of you and me”. But only he would know that. For Miss Barbara Shuttleworth, the soon-to-be Mrs Barbara Lupton, Friday 30th July 1948 was a day like no other. It started pretty ordinary. At 7am she awoke; washed, dressed and ate an apple. At 8am, elegantly dressed in a blue-and-white cotton dress, a black hat and black shoes, she left home with a spring-in-her step, hopped on the Bayswater tube to Westminster, and by Big Ben, sashayed through the stiff suits on Parliament Street and breezed into No 1 Derby Gate, as if she was walking on air. As a librarian at the House of Commons, Barbara was like a ray of light in a grey room of gloom, but even more than usual, her colleague Pauline Bebbington said she seemed joyous but also nervous. Today was a big day. At 4:30pm - with a key, a tape measure and her mother Gwendoline - she would head to 29 Highgate West Hill in Hampstead and decide on the furniture and fittings of her new home. …but first, she needed to set the record straight. At exactly 12:45pm, with only a one-hour break, a thirty-minute journey to make and no time to dither, needing to be back at work by 1pm at the latest, she packed up, dashed-out, apologised to Pauline for missing their lunch date - “Sorry sweetie, let’s do it Monday okay?” - and caught a taxi to Queensway. Arriving at Ralph Court, just shy of 1:15pm, she exchanged a pound to pay the taxi with Charles Hadden the porter, took the lift up to the seventh floor, and with the red bricked mansion block being a u-shape around the floral courtyard, at the far end of the corridor, she rang the doorbell to flat 147. As a three-bedroom flat owned by landlady Margaret Reidl, who was out, she was greeted by lodger Mira Milivojevic who was just leaving, and as Felic - who had taken a sleeping pill the night before - still wasn’t awake, Barbara was let in, left alone, and there are no witnesses to what happened next. At 1:45pm, the cleaner Mrs Beatrice Benham arrived; she heard no sounds, she saw no people and assuming the flat was empty, she started cleaning the kitchen. Ten minutes later… (three bangs in quick succession, a short pause, a bang, a pause and another bang)… came from Felic’s bedroom. The courtyard filled with screams, the flat buzzed with panicked people, the porter tried to bash down the bedroom door, and with the police called at 2:03pm, they arrived by 2:07, but it was too late. Felic’s bedroom was a small bed-sitting room with a single bed, a desk, an arm chair, a wireless radio and a small balcony window overlooking the courtyard. Being a meticulous military man, it was smart, neat and sparse, but with every item listed on a very precise inventory, as if he was planning to leave. On a rail hung his uniform, all pressed and starched. On his desk were his medals, his family photos, a wedding ring, a gold locket and two gold medallions. On his bedside table was a glass of water, a pot of sleeping pills, his horn-rimmed glasses, his diary, a pen, a book of Polish poetry, an unopened letter to Barbara, a sealed letter to his son, the inventory of all his worldly possessions, and his Last Will & Testament. On the floor was a gun, Felic was missing and lying on his bed was Barbara. According to the Police Investigation, this is what happened. Felic had made his decision. As he and Barbara were “lovers”, either they would live together, die together, or if he couldn’t have her, then no-one could. That was his plan. But having had a fitful night’s sleep and taken a sleeping pill, he had overslept. So, although he dreamed of looking resplendent on his last day alive dressed in his crisp uniform, shiny boots and gleaming array of medals, at 1:15pm, as Barbara knocked on his bedroom door, he was dozy, tired and wearing just his pyjama bottoms. What was said will never be known, as no words between them were ever heard. But in an unopened letter to Barbara, he had wrote “Do you love me still, or is all over now? Are you in love with somebody else? I lost six years for you. I send for divorce in Poland. It’s your bad deed. Do you believe in God? If so, say your prayer. We will die together. You have broken my life. I will break yours”. Barbara had only planned to be here for just ten minutes, but she had been here for almost forty, and she knew if she didn’t leave now, she’d be late for work, to meet her mother and to see her new home. At 1:55pm, Barbara was sitting on the bed, Felic was standing by the door and from his desk he pulled a revolver; there were no shouts and no screams, just three quick shots, then a fourth and a fifth. With the gun muzzle flush to her hairline, firing at point-blank-range which flashed black powder burns between her left ear and eye, the first shot ripped through her left temple, eviscerated her left and right temporal lobe, and shattered the right temple, causing extensive haemorrhaging to her brain. Almost immediately, Felic fired a second shot. With Barbara still sitting upright but slumping forwards, a bullet smashed her third rib, pierced her left lung and the seventh rib of her back, leaving a deep red stain on her blue-and-white dress, just above her heart, and although he wasn’t dead, but paralysed, with her left lung having collapsed, her chest cavity filled, and she began to drown in her own blood. The third shot came within a second of the last, but this wasn’t for her, this was for him. With his suicide pact almost complete, to ensure a blissful afterlife with his beloved, he placed the gun in his gaping mouth, the barrel flat against his palette and with the muzzle pointing to his brain, Felic fired, the right of his skull erupted in a thick red mist, and with a heavy thud, he slumped to the floor. …but he wasn’t dead. Somehow, he had survived. Picking up the gun, into his mouth, he fired it again. But still, he didn’t die. Why? He didn’t know. He had felt the hot fiery flash in his mouth, he could taste the acrid cordite on his tongue, and up his bedroom wall, down his heaving chest, onto his trembling hands and soaking his pyjama bottoms was his blood, but he was still breathing and still alive. He fired a fifth shot, this time, into his heart… only he missed, and hit his left arm. With the gun being a six-shooter, he knew he would only have one shot left, one chance to end it all, so – desperate to die and be with Barbara – he put the muzzle of the gun flush to his temple… and fired. (Click. Click. Click) Only it was empty. There was no sixth bullet. And he had only one option left. At 1:55pm, having snuck up to the roof for a sneaky cigarette, Charles Hadden the porter heard several shots in quick succession, “I then saw Mr Sterba at his bedroom window, stood on the sill, half naked, looking down, he hesitated for a second, sank down on his haunches, then rolled off”. Felic plunged seven floors, roughly seventy feet and landed hard. His upper body smashed onto a brick wall, and his lower body hit the concrete slabs, one foot below. But miraculously, again, he didn’t die. At least, not there and not yet. The ambulance arrived at 2:08pm. Felic had sustained twelve broken ribs, a fractured pelvis, a broken left hip, foot and femur, both lungs collapsed, both kidneys and spleen ruptured and three bullet wounds to the arm, mouth and head, he was admitted to Paddington Hospital but died at 2:42pm. Three minutes later, having detected a very faint pulse, Barbara also admitted to Paddington Hospital. She was given blood, plasma and began to show signs of recovery, but by the time her fiancé Thomas had arrived, it was too late. At 8:40pm, Barbara Shuttleworth died with mother at her side. (End). Next to his bed, Felic had left his Last Will & Testament. In it he left almost everything to his ex-wife (Maria); his gold ring, his watch, his locket, his medallion, his bank balance totalling sixty-seven thousand pounds which was to be used for the education of their son and the deeds to their home in Zakopane, which he had legally signed over to her - ironically - on the day Barbara had got engaged. In a letter to his son Andreij, he wrote “My son. Please excuse me for the things which happened, but my life is broken. It happened, I don’t blame anybody, and I myself am not to be blamed. Be a good man and take me as an example until my fiftieth year of age. Afterwards I was a weak man and broken through hard fate. She is a bad woman, Barbara, she influenced me to my divorce, proceedings of which, though happy, I did not start. That is what it seems to me now. My life is broken. She is very bad, but I love her, therefore I take her with me. Pray for my poor soul. Your father. F Sterba”. An inquest was held at Westminster Coroner’s Court on 6th August 1948, and with the jury not even needing to retire to consider their verdict, it was declared that Felic Sterba had murdered Barbara Shuttleworth and then committed suicide whilst the balance of his mind was disturbed. Barbara Shuttleworth was twenty-six-year-old; she was a lovely girl, with good job, a happy family and a bright future, whose radiant smile illuminated rooms, whose charm made people truly love her and whose warmth and compassion for others lead to a really beautiful person to lose her life far too early for no reason. She was due to marry Thomas Lupton a few days later, but instead, she was buried. OUTRO: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for listening to Murder Mile. Don’t forget, Extra Mile in next so pop your tea on the hob and a cake in your gob as it’s time to chow down and witter about nonsense. Before that, a thank you to my new Patreon supporter who this week is Mhairi McCrae, I thank you. As well as a thank you to all Patreon supporters whether old or new, previous or impending, as well as everyone who leaves reviews, comments or shares this podcast with their friends. I thank you. Murder Mile was researched, written & performed by myself, with the main musical themes written and performed by Erik Stein & Jon Boux of Cult With No Name. Thank you for listening and sleep well.

Michael J Buchanan-Dunne is a writer, crime historian, podcaster and tour-guide who runs Murder Mile Walks, a guided tour of Soho’s most notorious murder cases, hailed as “one of the top ten curious, quirky, unusual and different things to do in London”, nominated "one of the best true-crime podcasts at the British Podcast Awards 2018", one of The Telegraph's top five true-crime podcasts and featuring 12 murderers, including 3 serial killers, across 15 locations, totaling 50 deaths, over just a one mile walk

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael J Buchanan-Dunne is a crime writer, podcaster of Murder Mile UK True Crime and creator of true-crime TV series. Archives

July 2024

Subscribe to the Murder Mile true-crime podcast

Categories

All

Note: This blog contains only licence-free images or photos shot by myself in compliance with UK & EU copyright laws. If any image breaches these laws, blame Google Images.

|